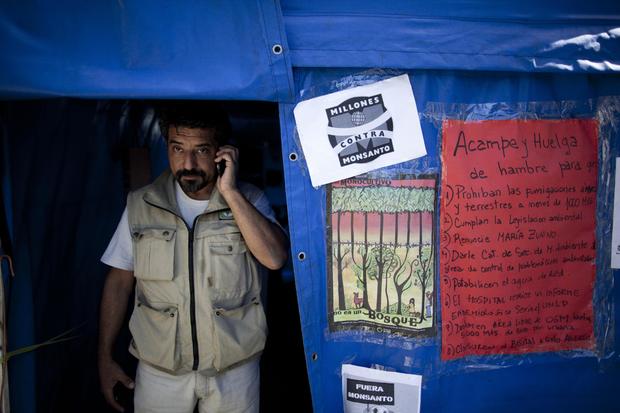

Agrochemicals health crisis in Argentina

Tomasi's job was to keep the crop dusters flying by quickly filling their tanks, but he says he was never trained to handle pesticides.

Now he is near death from polyneuropathy. "I prepared millions of liters of poison without any kind of protection, no gloves, masks or special clothing. I didn't know anything. I only learned later what it did to me, after contacting scientists," he said.

Read more: Argentines link health problems to agrochemicals

Instead of a lighter chemical burden in Argentina, agrochemical spraying has increased eightfold, from 9 million gallons in 1990 to 84 million gallons today.

Glyphosate, the key ingredient in Roundup products, is used roughly eight to 10 times more per acre than in the United States. Yet Argentina doesn't apply national standards for farm chemicals, leaving rule-making to the provinces and enforcement to the municipalities. The result is a hodgepodge of widely ignored regulations that leave people dangerously exposed.

American biotechnology has turned Argentina into a commodities powerhouse, but the chemicals required aren't confined to the fields - they routinely contaminate homes, classrooms and drinking water.

Now a growing chorus of doctors and scientists is warning that uncontrolled spraying could be causing the health problems turning up in hospitals across the South American nation.

In the heart of Argentina's soybean industry, house-to-house surveys of 65,000 people in farming communities found cancer rates two to four times higher than the national average, as well as higher rates of hypothyroidism and chronic respiratory illnesses.

Most provinces forbid spraying next to homes and schools, ranging in distance from 50 meters to as much as several kilometers from populated areas.

But The Associated Press found many cases of soybeans planted only a few feet from homes and schools, and of chemicals mixed and loaded onto tractors inside residential neighborhoods.

The country's entire soy crop and nearly all its corn and cotton have become genetically modified in the 17 years since the St. Louis-based company promised larger yields.

Agrochemical spraying has increased eightfold. After Gatica's newborn died of kidney failure, she filed a complaint in Cordoba province that led last year to Argentina's first criminal convictions for illegal spraying.

The country's entire soybean crop and nearly all its corn and cotton have become genetically modified in the 17 years since the St. Louis-based Monsanto company promised huge yields with fewer pesticides using its patented seeds and chemicals.

Instead, the agriculture ministry says agrochemical spraying has increased eightfold, from 9 million gallons in 1990 to 84 million gallons today.

Although it’s nearly impossible to prove, doctors say Aixa’s birth defect may be linked to agrochemicals.

In Chaco, children are four times more likely to be born with devastating birth defects since biotechnology dramatically expanded farming in Argentina. Chemicals routinely contaminate homes, classrooms and drinking water.

Carrasco found that injecting very low doses of glyphosate, a weed-killer, into embryos can change levels of retinoic acid, causing the same sort of spinal defects in frogs and chickens that doctors are increasingly registering in communities where farm chemicals are ubiquitous.

Teachers say the farm that abuts their school yard has been illegally sprayed with pesticides, even during class time.

In Entre Rios, teachers reported that sprayers failed to respect legally required 50 meter setbacks outside 18 schools, and doused 11 of them while students were in session. Five teachers have since filed police complaints.

Alvarez blames continuous exposure to agrochemical spraying for two miscarriages and her son's health problems.

Chaco provincial birth reports show that congenital defects quadrupled in the decade after genetically modified crops and their related agrochemicals arrived.

Glyphosate represents two-thirds of all agrochemicals used in Argentina, but resistance to pesticides is forcing farmers to mix in other poisons such as 2,4,D, which the U.S. military used in "Agent Orange" to defoliate jungles during the Vietnam War.

Most Argentine provinces limit how close spraying can be done in populated areas, with setbacks ranging from as little as 50 meters to as much as several kilometers. But The Associated Press found many cases of soybeans planted only a few feet from homes and schools, and chemicals mixed and loaded onto tractors inside residential neighborhoods.

American biotechnology has turned Argentina into the world's third-largest soybean producer, but the chemicals powering the boom aren't confined to soy and cotton and corn fields.

They routinely contaminate homes and classrooms and drinking water. A growing chorus of doctors and scientists is warning that their uncontrolled use could be responsible for the increasing number of health problems turning up in hospitals across the South American nation.

Earlier this year, Di Vincensi stood in a field waving a court order barring spraying within 1,000 meters of homes in his town of Alberti; a tractor driver doused him in pesticide.

As Argentine ranchers turn to higher-profit soybeans, formerly grass-fed cattle are fattened on corn and soy meal in feedlots.

Doctors told Camila's mother, Silvia Achaval, that agrochemicals may be to blame. It's nearly impossible to prove that exposure to a specific chemical caused an individual's cancer or birth defect, but doctors say these cases merit a rigorous government investigation.

"They told me that the water made this happen, because they spray a lot of poison here," said Achaval.

San Roman says that when he complained about clouds of chemicals drifting into his yard, the sprayers beat him up, fracturing his spine and knocking out his teeth.

"This is a small town where nobody confronts anyone, and the authorities look the other way," San Roman said. "All I want is for them to follow the existing law, which says you can?t do this within 1,500 meters. Nobody follows this. How can you control it?"

The twins' mother, Claudia Sariski, whose home has no running water, says she doesn't let her children drink the water from the discarded pesticide containers.