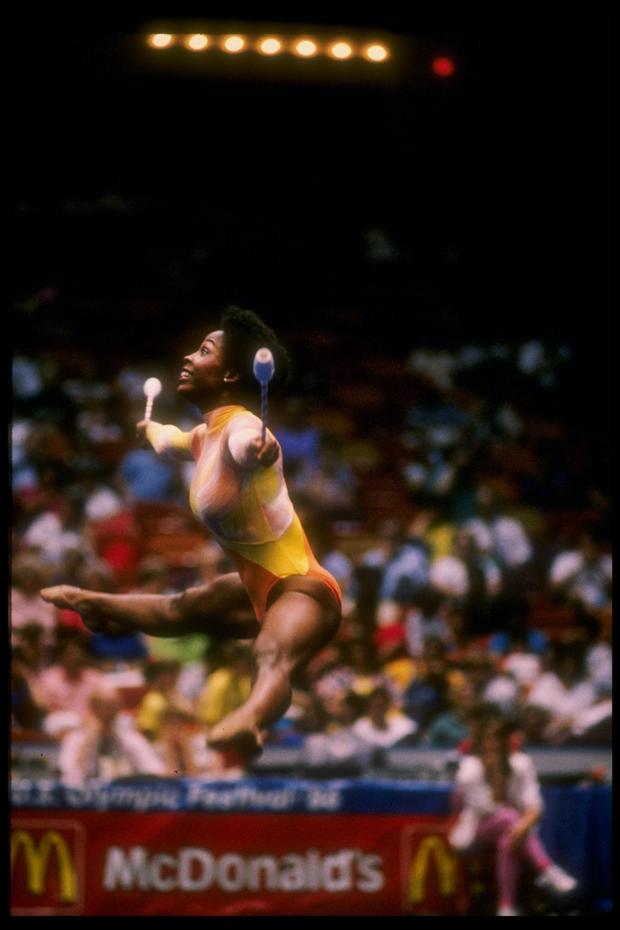

Black History Is Our History: World Champion Gymnast Wendy Hilliard Uses Her Own Experience To Encourage Next Generation Of Black Athletes To Succeed

NEW YORK (CBSNewYork) -- When faced with bias, world champion gymnast Wendy Hilliard used it to propel herself across the mat and to encourage the next generation to succeed.

Hilliard fell in love with the sport of gymnastics at an early age, and it was simple.

"I enjoyed going upside down. There's something about being able to move your body and have such control that excited me," Hilliard told CBS2's Otis Livingston.

Hilliard was able to satisfy that excitement for tumbling at the Y in inner-city Detroit, but to get access to the bars and beams, she'd have to venture out to the suburbs, which provided challenges.

"I had to travel far and it cost a lot of money, and there weren't a lot of Black people doing gymnastics, but I loved the sport. If you find something you love, you just do it no matter what," she said.

Eventually, Hilliard decided on rhythmic gymnastics and success soon followed as she became one of the best in the country, but even her lofty ranking didn't shield her from racism as she prepared in Colorado Springs for the world championships in 1983; she was denied a spot on the team.

"I went up to the coach and I said, 'How come I'm not on the team?' She said, 'Oh Wendy, you stand out too much.' And I just was, like, 'I don't like your face.' Like, what? I couldn't really grasp that, I was just so upset," Hilliard said.

Undeterred, Hilliard's family made phone calls and sent faxes to U.S. Gymnastics.

The decision was reversed. The team would be selected based on national championship rankings. Hilliard made the team.

She would represent the U.S. in international competition a record nine years, including three world championships, earning national and international gold medals.

But she never forgot that experience in Colorado Springs, giving her the impetus to become an advocate for other Black athletes.

Thus, the Wendy Hilliard Foundation was born, serving 1,500 kids a year in Harlem and another 500 in her native Detroit.

"My foundation is to improve physical and emotional health by providing free and low-cost gymnastics in urban areas," Hilliard said.

She's had some help getting and keeping young girls interested in the sport.

"Along comes Gabby Douglas, right? Wins the Olympic gold medal, and so now all these little girls are like, 'Oh, I can do that, too,'" Hilliard said.

Hilliard thinks it's important to have people who look like the students teach them, inspiring them to new heights.

And that's what Black history means, knowing where you come from and being inspired about what you can achieve.

"There are even those breaking barriers before me, like, 20, 30, 40 years before me in the sport," Hilliard said. "It's important that people know their history. It's important that they see that people have gone, broken barriers before them and it can be done."

Not even the pandemic has shut Hilliard down. Her team just shifted from the Armory to online to cater to the students' needs.

"We have really great staff, and they turned it around on a moment," Hilliard said. "When we had to go online to do virtual, they were able to engage the kids. And they would just put on their leotards in their living room and pull out a yoga mat and do their cartwheels, and so it was something familiar and fun."

"Do you feel like you are a pioneer?" Livingston asked.

"I didn't go out to be a pioneer. I went out because I love gymnastics, and then the other love was really wanting to give others the experience I had. The joy and what I get back from the kids, it keeps me going. It's very joyful," Hilliard said.