As hunger crisis continues, local nonprofits struggling to keep up with demand

NEW YORK -- One Brooklyn nonprofit that helps stock the shelves of smaller pantries says it's providing ten times more meals now than before the pandemic.

The nonprofit's director tells CBS2's Lisa Rozner grains are some of the hardest items they've been able to get for low-income New Yorkers.

The first humanitarian cargo ship carrying thousands of tons of wheat from Ukraine since Russia's invasion in February is headed for an African country. The goal is to get grain back into global markets.

It's a deal brokered by the UN World Food Programme. Ertharin Cousin is the former executive director.

"People should care because about 27-30 percent of all the grains and essential oils in that global food trading system comes from Ukraine and Russia. And when that food is not part of the system, it creates increased prices," she said. "The second reason people should care is because there are a number of countries like Somalia, for example, where they're suffering from their third year of drought. And they depend upon imports directly from Ukraine."

Somalia is one of the places the humanitarian organization Action Against Hunger, which is headquartered in New York City, has boots on the ground. The organization says some families have had to move away from rural regions because there is no longer water available for daily use.

"They are not able to farm where they used to farm, you know, and rely on, on, on their food as their food, food source," said Ahmed Khalif, with Action Against Hunger Somalia. "One, uh, Amina Mohamed told me that she had to reduce the number of meals her family will consume in a day. And she, she also has to make, uh, difficult choices in terms of who among our children will be fed for."

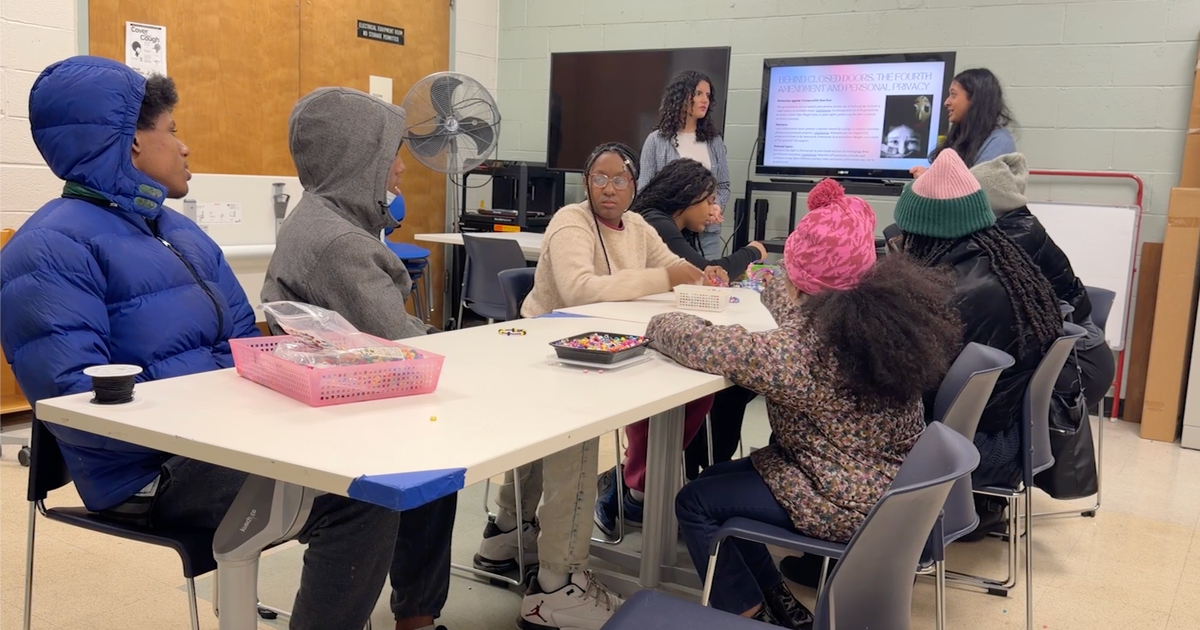

In the United States, the nonprofit Campaign Against Hunger in East New York showed CBS2 the five shelves holding grains out of the 30 that used to be stocked.

The organization distributes food to 14,000 families every week and supports 165 smaller pantries. Director of Programs Tamara Dawson says because of increased prices, they're only able to distribute half of what they used to.

"Prior to this hunger crisis, the average bag would have enough to feed a family of four, nine meals, three meals per day, and so that would be double what we have here," she said.

Several of the empty shelves would typically be for bread but the campaign says it's just so expensive they haven't purchased any in months.

"Today you see quinoa, and that's the only grain that's currently on the list because that's all we have due to the need, but typically you'll see whole grain pasta, regular pasta, you'll see rice," Dawson said.

The restaurant The Migrant Kitchen is limiting pastry options, but the crisis is also making it harder for giving back through Migrant Kitchen Initiative, which feeds communities in need.

"It affects margins, and so it puts a greater strain on the foundation to bring in private support to help supplement what we're doing," said Jaclinn Tanney, cofounder of the Migrant Kitchen.

The restaurant recently joined the rewards app Seated in hopes of increasing sales. The cofounder says a portion of the profits are what fund its efforts like reaching low-income residents who are homebound.

As for whether these shipments will turn things around? One expert says it's complicated for the United States.

For example, CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute Director Nicholas Freudenberg says, "Before the pandemic, a really strong consolidation of the food industry, where just a few companies now control much of the world's food supply. And so those companies have used the shortages to raise prices."

He says logistical hurdles may still stand in the way, and some experts say, depending on that, it could be months or years before there's significant improvement.

Several of these organizations say they're also struggling to get volunteers. Find out how to get involved: