NJ Goes High-Tech To Eliminate Prison Cell Phones

TRENTON, N.J. (AP) -- The dark gray device used to detect cell phones looks like an oversized walkie-talkie.

When Scott Schober, president of a Metuchen technology company, flipped it on in an officer cafeteria at a New Jersey jail several months ago, a warning immediately flashed.

"I turned around and walked out and said, 'You've got phones in there,"' he said, describing the demonstration he gave for officials. "They basically said, 'We're not surprised."'

Cell phones are illegal in jails and prisons, and officers are supposed to be on the front lines of keeping them out. For Schober, the incident highlighted the pervasive nature of a problem that has dogged prison officials here and around the country.

State and county corrections officials in New Jersey are quietly testing new technology as they step up efforts to stem the tide of illegal phones behind bars. Department of Corrections Commissioner Gary Lanigan said an internal committee is examining whether to invest in detection equipment, along with recommending ways to improve security.

Law enforcement officials say phones can be as dangerous as weapons and allow inmates to continue terrorizing neighborhoods long after they've been locked up. Prisoners with cell phones have directed gang activity. They have intimidated witnesses. One inmate at New Jersey State Prison in Trenton allegedly ordered, over a cell phone, the murder of an ex-girlfriend who testified during his trial.

But despite security upgrades and increased penalties for having phones in prison, there are signs the problem is getting worse in New Jersey.

Inmates are making fewer calls on prison land lines, which can be monitored by officers. Meanwhile, the number of phones found in prisons has increased 50 percent over the last year. The most phones, 190 of 259 this year, were in Northern State Prison in Newark, one of the state's most secure facilities.

"There are routinely finds of cell phones that you don't hear about," Lanigan said. "Searches have been enhanced. They just have to be enhanced more."

With phones costing $500 on the prison black market, some officers have allegedly sought a cut of the action.

On Sept. 23, authorities announced the indictment of former corrections officer Luis Roman, saying he circumvented security by stashing phones and drugs under his protective vest or in his boots, then used a network of inmates to distribute them inside the prison.

Lanigan said officers can make $40,000 a year smuggling contraband into prisons, calling it an "inducement" for corruption.

"I can't stand here and say we don't have corrupt employees," he said.

Jim McGonigal, president of the New Jersey Law Enforcement Supervisors Association, which represents corrections sergeants, said pursuing high-profile cases against officers helps deter future corruption.

"We have to send a message to the staff: If you do something stupid like this, there's going to be consequences," he said. "I don't mean taking away your pension. I mean serious jail time."

Corrections started tracking phone seizures separately in August 2008. Over the next year, 266 phones were found in prisons, according to officials. Then, from August 2009 to July 2010, 339 phones were found, a 50 percent increase.

Corrections spokeswoman Deirdre Fedkenheuer said more seizures are the result of more searches.

"The searches will continue to be vigorous and frequent, the prosecutions for corrupted staff, visitors and inmates will go on, and we are not ruling anything out in our pursuit to rid the prisons of cell phones," she said.

Lanigan says the ultimate solution is to legalize jamming cell phone signals in prisons, now banned by the Federal Communications Commission. He is one of many prison officials across the country who, along with elected leaders including Gov. Chris Christie, are pushing a bill in Congress to change that.

The bill has already cleared the U.S. Senate, but the version in the House of Representatives is still in committee.

A group advocating for cell phone companies has opposed the bill, and companies that sell alternate technologies criticize jamming as clumsy and raise concerns it could block legitimate communication near the prison.

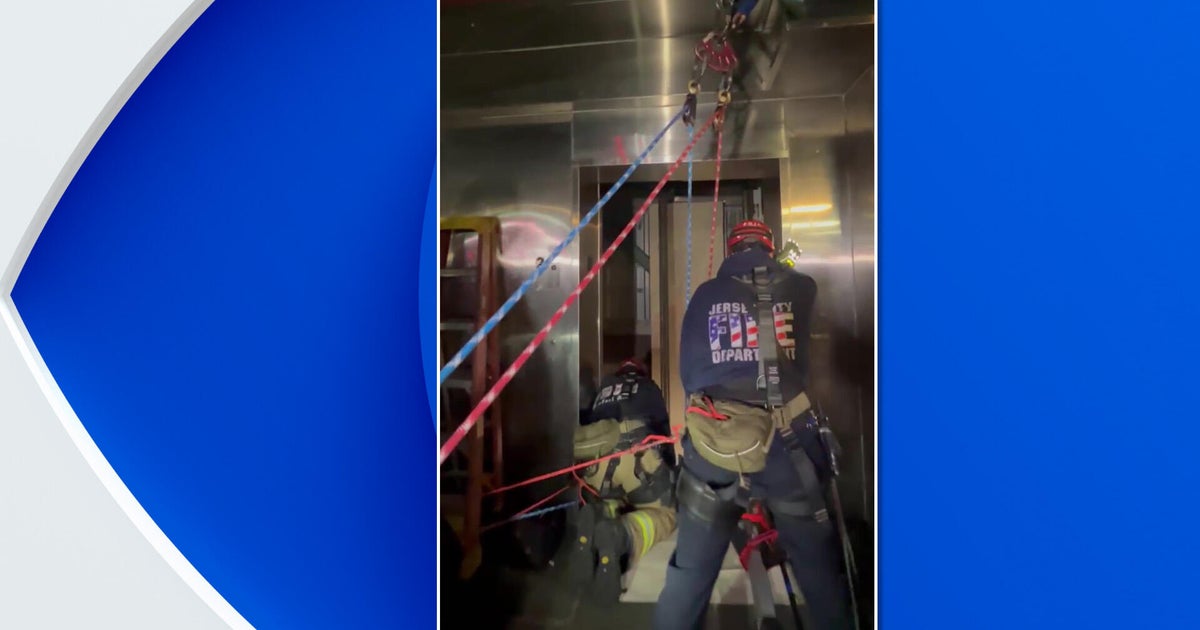

Some prison systems have implemented other measures.

Mississippi recently became the first state to install antennas that intercept cell phone communications within a prison. When someone tries to send a text message or make a call, the antenna catches the signal and checks a database to see if it came from a registered number.

Authorized calls are rerouted to commercial carriers, while unauthorized calls are stopped. In one month, the state blocked 216,320 communication attempts, Mississippi officials said.

Fedkenheuer said the technology may not be the right fit for New Jersey because there's no need to allow authorized calls all cell phones are banned from state prisons.

There are other methods to detect and locate phones in prisons. For example, New Jersey was the first state to train dogs to hunt phones.

Others, like Schober's company, are pushing high-tech options. Schober said his handheld devices can detect the signals cell phones send when turned on or transmitting data. A directional antenna helps locate the phone. He said his company has sold about two dozen devices in New Jersey, but won't say who bought them.

Lanigan believes jamming prison phones is the future. It's the best way, he is fond of saying, to turn a cell phone into a "4-ounce piece of garbage."