Palladino: NFL Must Listen To Harry Carson On Concussion Dangers

By Ernie Palladino

» More Ernie Palladino Columns

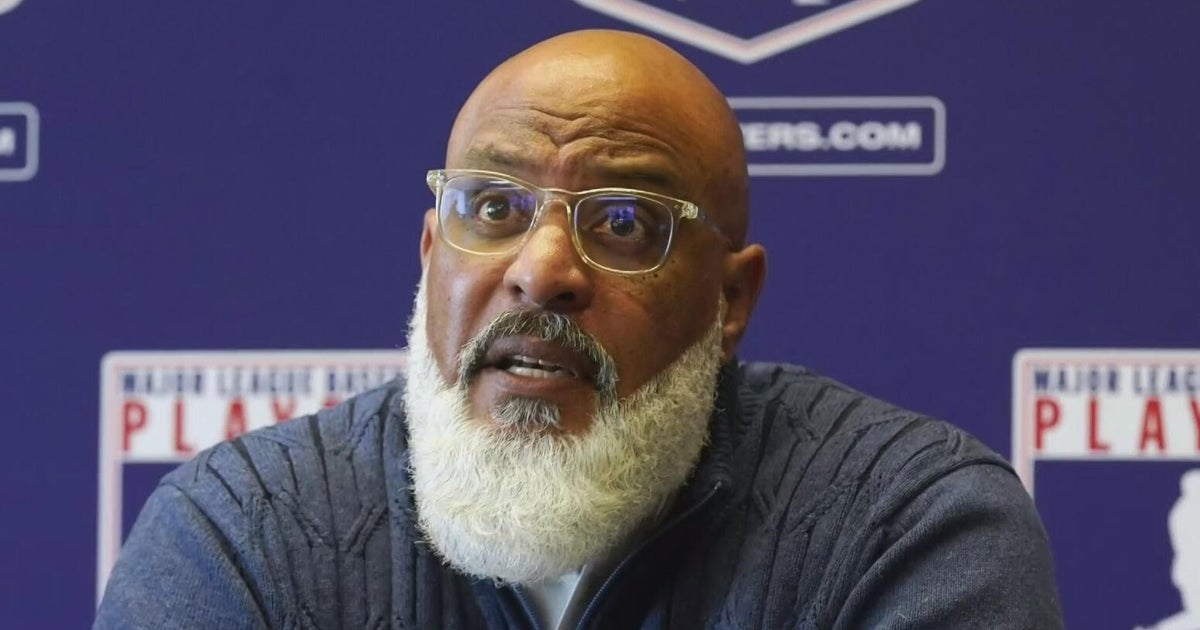

Harry Carson won't let his 6-year-old grandson play tackle football. Not at any age, not in any program.

If the NFL needed any further evidence that its concussion problem has grown out of control, the league's power people needed only to listen to the Hall of Fame linebacker's testimony before the New York State Assembly on May 4 about his own experiences and concerns over post-concussion syndrome.

The fact that this former Giants warrior told lawmakers in open session that he will prohibit his grandson from tackle football further underlined the growing concern of parents nationwide over the safety of football. In supporting an assemblyman's longshot bid to ban tackling for players under 13 years of age, Carson again brought into focus the NFL's continuing denial that the slamming of heads attached to large bodies flying around a gridiron at warp speed is simply not good for one's noggin.

It seems nonsensical that the league only recently let slip that concussions and head contact are indeed related. And it is nothing short of disturbing that congress, in a report out of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, accused the league of trying to re-direct part of its $30 million grant away from the National Institute of Health's work on head trauma because it objected to one of the researchers involved.

But for now, let's forget about the NIH clinicians that have uncovered the ever-growing incidence of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy that has driven thousands of former players into the mental abyss. The fact that Carson -- a player who rose to the highest level of a sport that afforded him not only a living, but fame as one of its best -- has barred a young family member from any participation in football should catch the league's attention.

Carson's words should also come as a warning to the league that football -- the sport, not the $10 billion industry that the NFL has become -- sits on a dangerous precipice. With parents all over the country turning their children away from football, the trend could have a trickle-up effect and endanger the league's very existence down the road.

That's why the NFL must admit without equivocation the dangerous relationship between head contact and head trauma. Only then can the league start doing something about the issue, beginning with increasing the $1 billion that covers the future care of some 20,000 retirees.

Of course, that would require the league to take the long view on the problem. That's unlikely. Their big tobacco-like reluctance to go whole hog on the research is based on the sport's popularity. Television spends loads of money on broadcast rights. Millions of bettors wager billions of dollars on these weekend gladiators, thus spurring interest and advertising dollars.

The last thing NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell and the owners want to do is kill the golden goose.

Meanwhile, things are happening. The researchers go about their work, dissecting their collection of brains from dead players and continue to grow the mountain of evidence proving football's inherent dangers. A new scan developed at New York's Mount Sinai Hospital shows the potential of detecting CTE in living players.

The image of a 39-year-old subject's brain -- a retired NFL veteran who sustained several concussions -- was striking.

That's huge. But that won't exactly be music to Goodell's ears, either.

As damning as the empirical evidence might be, the league will continue to find a way to shrug it off, delaying a definitive recognition with the same old argument about premature and inconclusive research.

Carson's case is anecdotal. But in an important way, he should become the most compelling reason for the NFL to change its stance from resistance to acceptance.

He was a star.

A leader.

A beloved member of the Giants franchise.

A sufferer of the ravages of concussions who won't consign his grandson to the same dangers.

The NFL needs to listen to him.

Follow Ernie on Twitter at @ErniePalladino