A look at the history of New York's bail reform law with Bronx DA Darcel Clark

NEW YORK - Bail reform is one of the most polarizing topics in Albany. It even has Gov. Kathy Hochul negotiating a compromise to implement changes to the law.

CBS2's Aundrea Cline-Thomas takes a look at how it all started.

As violent crime continue to rise in New York City, law enforcement to lawmakers are taking aim at bail reform. Mayor Eric Adams is among the staunchest critics.

"2019-21, the number arrested for homicide out on bail for gun offenses tripled, tripled. We're talking homicides. We lost lives," Adams said.

Historically, bail was established only as an incentive for defendants to return to court.

"Bail is not meant to be punishment. It is not a system of punishment," said Marie Ndiaye, an attorney with the Legal Aid Society. "Under our Constitution, if you are arrested, you are innocent until proven guilty."

But bail resulted in the mass incarceration, mainly of people of color. In 2019, while Black New Yorkers made up 24% of the city's general population, they were 50% of people charged in criminal court, and 56% sent to jail pretrial.

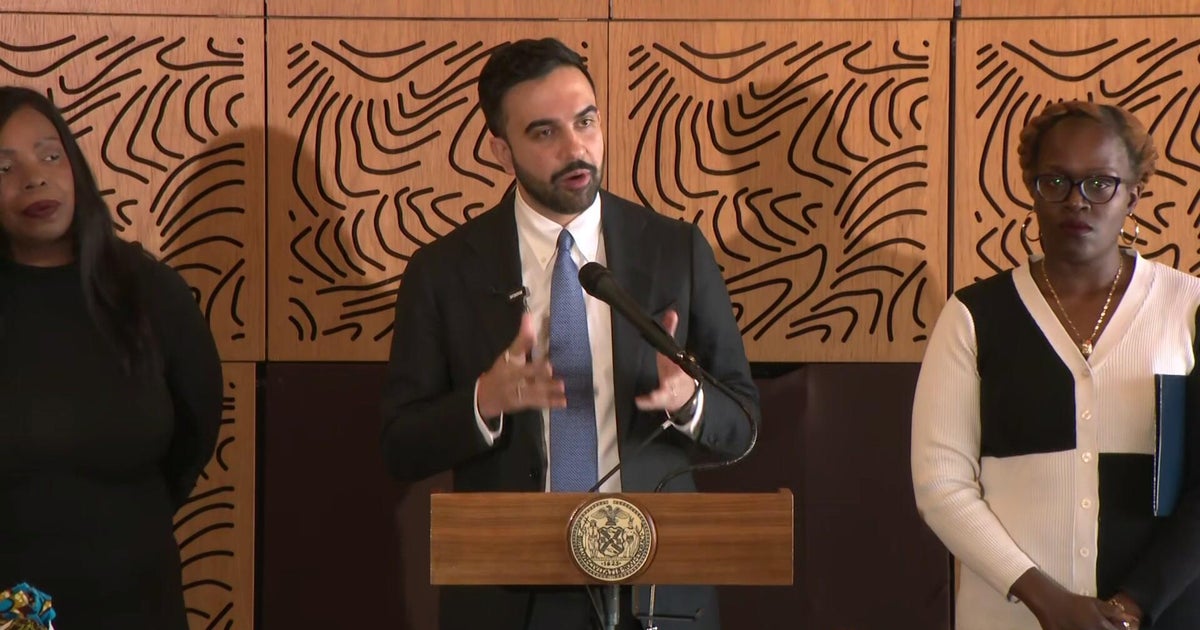

Bronx District Attorney Darcel Clark remembers her early years as a prosecutor in the 1980s.

"The answer was law enforcement just sweep up everybody, the whole community, everybody," Clark said. "And I was a prosecutor then and our job was, they brought them in, it was nail them and jail them."

"That's how we thought we kept the community safe. We know now better than that," Clark added.

But in 2015, Kalief Browder became the face of the impact of that approach. Browder took his own life following his release from Rikers Island, after spending years behind bars unable to post bail on low level charges that never went to trial.

In fact, most defendants are unable to post bail, resulting in jail time.

"Incarceration of a couple of days, which most people, you know, assume it's no big deal, can really be catastrophic," Ndiaye said. "To housing insecurity, food insecurity, job insecurity."

The jail population sharply declined from nearly 22,000 in 1991 to just over 7,000 in 2019, when crime reached record lows, despite fewer people being behind bars. A vast majority were being held pretrial on a variety of offenses.

The bail reform law first implemented in January 2020, then rolled back under intense pressure that July, sought to address the disparities by eliminating cash bail for nearly all misdemeanors and nonviolent felonies. Meaning, those without money could remain free while awaiting trial.

When bail is set, judges also have to consider a defendant's means, not create a financial hardship, and provide easier options to pay.

"They have a better chance of seeing their case through without having to take a coercive plea, a better opportunity to not face any jail or prison time at all, and a better opportunity to not face a conviction at all," Ndiaye said.

As bail reform was being implemented, the COVID pandemic was also raging. Arrests plummeted. Courts became backed up as virtual proceedings went into effect. And by the summer of 2020, gun violence was also on the rise.

"Judges began setting bail more often when they had that discretion on cases where they had been releasing people," said researcher Michael Rempel, who's with the John Jay College of Criminal Justice. "The evidence to date doesn't suggest that it was bail reform that led to the uptick in gun violence."

While not being able to detain people on certain charges, in select cases, judges can use electronic monitoring, require treatment and other programs while defendants await trial as a part of an expanded supervised release.

"People are released on supervised release, that's a joke. The city hasn't well financed that," Clark said.

According to city data, of the tens of thousands of people awaiting trial from January 2020 to June of 2021, 5% or less were rearrested, mostly on misdemeanors. That translates to about 2,000 people each month.

"Are they re-offending in a different percentage than before the bail reform laws were put in place?" Cline-Thomas asked.

"There's no indication of that whatsoever," Rempel said.

New York is the only state that does not allow judges to consider public safety when setting bail or pretrial detention, a major factor critics of the law want to change.

"There's a small percentage that's causing the violence and the harm in our community. They're taking advantage of the bail reform that was put in place to provide that equity for everybody," Clark said.

The statistics mean nothing to the victims and traumatized communities.

The Bronx district attorney's office investigated 600 shootings last year alone, but Clark does not blame bail reform laws.

"I can't prosecute my way out of here, but we can do a lot of prevention to keep people from coming in the first place," Clark said. "We have to look at the root causes of crime. And it's not necessarily a law, it's what's happening in our community. We have people that live at the poverty level or below, they don't have jobs, the schools are not preparing our kids the way they should, people are homeless."

Providing more resources, Clark says, should be be a larger focus of the strategy, not an excuse.

"It's about time that we get the resources that we need in the Bronx," Clark said.

All while keeping jail and state prison for the most violent on the table.