New Jersey Education Chief Talks Getting Tough On Failing Schools

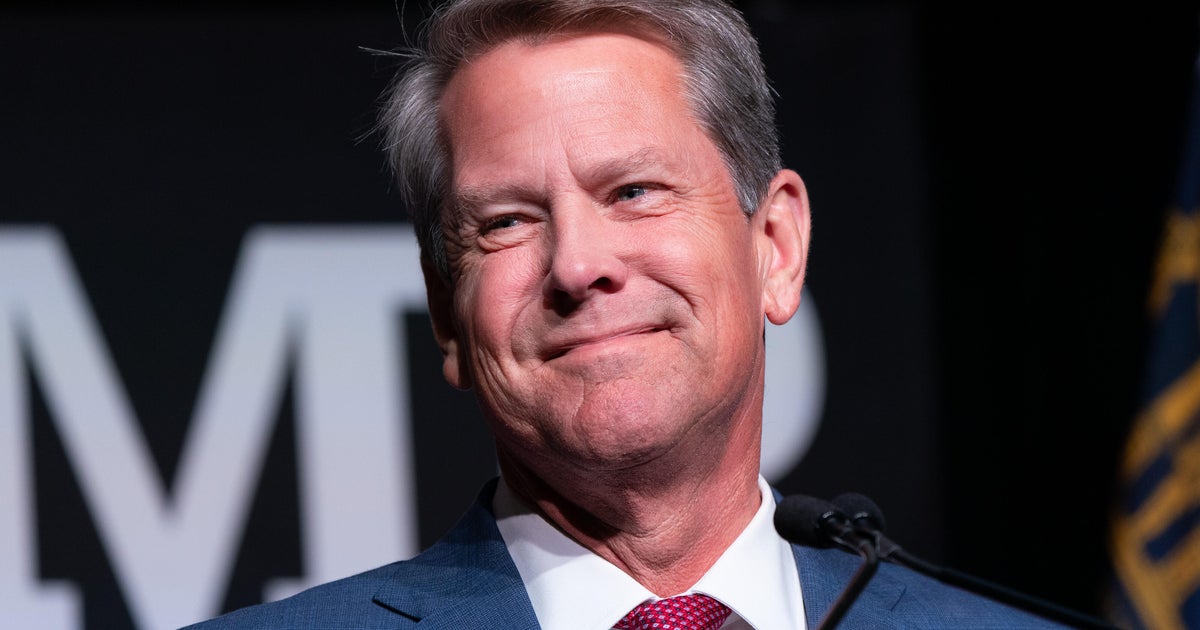

TRENTON, NJ (AP) - As New Jersey's acting education commissioner, Christopher Cerf is charged with carrying out Gov. Chris Christie's plans to overhaul some aspects of the state's public education system.

Along with the Republican governor, Cerf has often battled with the New Jersey Education Association, the state's main teachers union, which opposes the administration's plans to use test scores as part of a retooled mechanism to overhaul teacher evaluations, take away the lifetime job protections of tenure for educators and introduce merit pay for educators.

Cerf has previously worked as deputy chancellor of the New York City Department of Education and has worked for private education companies. He also spent four years teaching history at a high school in Cincinnati.

He gave an interview to The Associated Press last week on the state of New Jersey's schools and the changes he wants to make.

AP: What's the state of public education in New Jersey? How do we compare to other states?

Cerf: We compare very well from an aggregate perspective if you take the NAEP, the National Assessment of Educational Progress. New Jersey typically ranks within the top two to four in each of the four major categories.

It's a reflection of a very evolved, very developed, very successful education system in the main. The dissonance in that is if you get beneath the numbers, beneath the aggregates, you'll see that we have one of the largest achievement gaps in the nation.

One of the things that just gets my blood boiling a little bit on this is our achievement gaps in the schools, measured pretty any way you want to measure it, racially, ethnically or by poverty --- they're really jarring. The NJEA just put out a press release which I will tell you I find as offensive as anything I have seen in my long career in education, basically going, 'What's the big deal? It's not that bad.'

AP: Their argument was essentially that the gap is so large because the best-performing kids do so well.

Cerf: They had two arguments. The other one is: Our black kids are doing better than their black kids. --- Both of those are not helpful and indeed, I think, quite destructive arguments. To say that we have a large achievement gap because the top of the state is so high basically assumes that the poor black kids don't belong at the same strata. That seems to me to be really offensive to me to say we shouldn't actually expect the kids in Newark and Camden to be performing at the same level as the kids in Bergenfield.

The second argument is, again, the African-American kids here are doing better than the African-American kids in New Orleans. --- Does that mean that as a class, poor kids or kids of color, we want to see who wins the contest in that class? No. It's not that all. It's about: Can we give every kid an equal opportunity in education regardless of birth circumstances?

AP: Is it a problem that we're the highest-cost-per-student state?

Cerf: I don't think it's a problem. All of us who are citizens or government are managing scarcity, right? So we need to make decisions between hospitals and universities and schools and universities and highways and tunnels and so on. I would never say it's a problem that we spend so much. But it is a naive point of view to say that we can have that conversation in isolation from all the other social priorities.

AP: There have been some studies that suggest that standardized tests not only have trouble sorting out teachers in the middle, but also teachers who don't consistently score at the top and the bottom; they don't help you figure out who are your very best and very worst educators. Are they wrong?

Cerf: Every accountability system is flawed and problematic. That is certainly true in education. If the standard is, can we build an accountability system that is better than the one we have today and keep working as a society to improve it? That takes you down one path. If the other path is, 'Wow, this is potentially unfair because it may yield a result that we may not trust; therefore, let's not do it at all.'

It's a pretty fundamental divide. I think that there is so much trepidation and propaganda in this area. It's really hard to have a reasoned conversation about this. My own view is that the data is potentially one component of a satisfactory assessment system, but it had to be used in a very limited and very responsible way.

We need to build confidence in our teacher corps that we are doing this almost completely in order to enable them to get better as opposed to just trying to identify the low performers and quote exit them.

Any school reformer will tell you: You will do a great, great, great deal more for children turning below-average teachers into average or good teachers than you will exiting the truly poor performers.

AP: What are the main areas where you think you and the NJEA agree?

Cerf: It's very hard to tell because I don't know who the NJEA is. When I sit privately with the leadership, we have very rational conversations about things. When I read the screeds they publish and the billboards they put up and the political propaganda they distribute to legislators, then there's very little area of agreement. I don't really know how to answer that question.

We have very different missions.

My job is incredibly straightforward. I only represent the kids of New Jersey.

AP: If you were czar rather than acting commissioner ---

Cerf: Don't forget I'm a "Cerf,'' so I can't be a czar.

AP: --- And there were no other of these competing interests, what would be the first things you would do?

Cerf: I've got so many competing for the top it takes my breath away. I would be much more honest and much more impatient about schools that are failing kids. We tend to have a habit in public education of saying when a school fails it's because we haven't tried hard enough or put enough money into it or given it enough time or somehow we have failed to enable a school to be good.

The evidence is pretty clear that if we are incredibly honest and fact-based, we need to be much more patient and give schools an opportunity to get better and give them the supports they need. But if that doesn't work, we have to take dramatic action.

I would impose much higher standards so that graduating from high school actually means something, not that you have a degree but that you are actually ready to be launched into life prepared for the next phase of life. That involves changing a lot of what we do in terms of the curriculum we have, the assessments.

I would focus intensely on third-grade literacy because once again, the statistics are really unsettling. We have 40,000 kids today in New Jersey who are not reading at the proficient level and it's very, very, very hard for kids who go into the fourth grade not reading to catch up and keep up.

I think we need to have a much greater focus on identifying, promoting and retaining talent at all levels of the system.

(Copyright 2011 The Associated Press. All Rights Reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.)