Unearthing the history of Black New Yorkers buried at Green-Wood as we approach Juneteenth

NEW YORK - On Monday, millions of Americans will be commemorating Juneteenth, a federal holiday observed for more than a century but formally recognized just two years ago.

You've probably heard dozens of renditions of "Lift Every Voice and Sing," widely recognized as the Black National Anthem.

The lyrics were penned by writer and NAACP leader James Weldon Johnson. However, you may not have known that he and his wife, civil rights activist Grace Nail Johnson, are buried in Brooklyn's Green-Wood Cemetery.

"He was also a diplomat and active crusader against lynching," says Rachel Walman, Green-Wood's Director of Education. "He also is the reason that the NAACP is such a prominent organization."

You may also not have known the remarkable stories of Susan McKinney Steward, the first female Black doctor to graduate from medical school in New York State, and her sister Sarah Garnet, the first Black woman to be a principal of a New York City public school.

Their graves are just a few stops along a self-guided tour organized by Green-Wood on Monday, in partnership with ASNEAA, a nonprofit whose mission is to connect Black history and culture through research and education.

"The official recognition of Juneteenth as a new federal holiday was perfect timing to lift BIPOC ancestors interred at Green-Wood, most of whom were also committed to social justice activism and human rights advocacy," explains ASNEAA creator Shari Jones.

There are more than half a million people buried at Green-Wood, both unknown and well-known figures who have shaped our city and our country. Organizers say the goal of this tour is to unearth and preserve some of that history.

The trolley tour and commemoration program will include painting kindness rocks to leave at the graves, and making legacy bracelets.

"Every day we want to normalize BIPOC heritage and make it as traditional as all the heritage that we celebrate," says Jones.

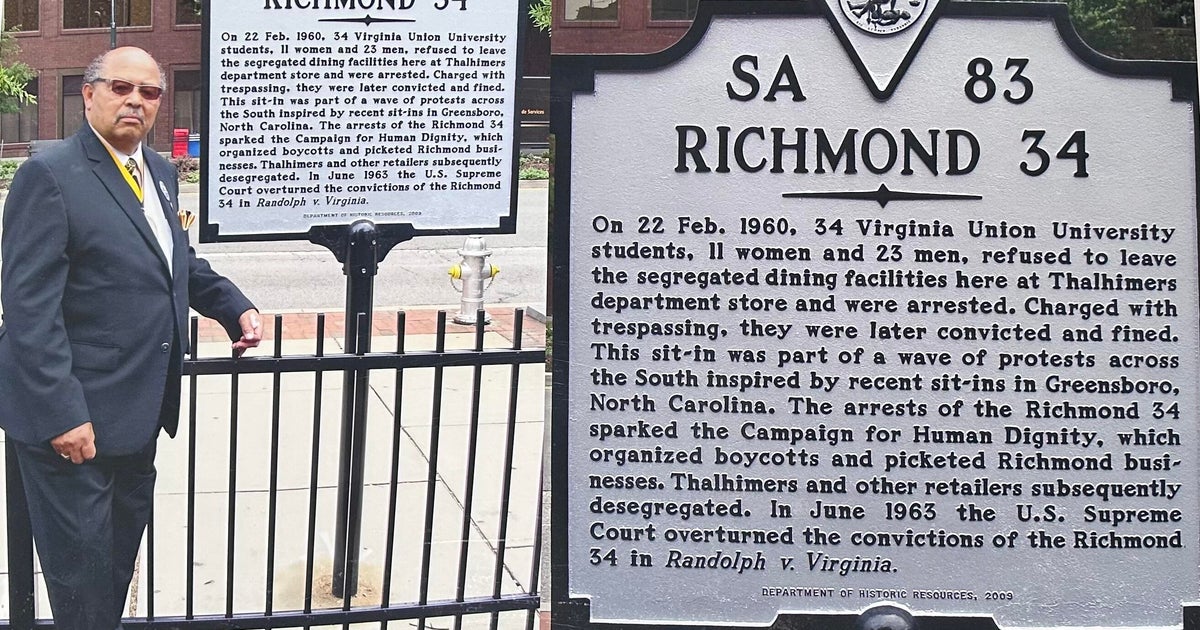

The final stop on our tour was a place called the Freedom Lots, which Walman believes is one of the largest Black burial grounds that has never been disturbed in the northern United States.

It's a section of the 185-year-old cemetery that serves as the final resting place for thousands of Black Americans.

"The cemetery does have a history of segregation in some respects," Walman explains. "That seems to be an area that the cemetery steered Black people toward or that Black people congregated in. A lot of the graves were purchased by social service organizations that worked with the Black community in New York City at the time."

Colorful rocks and shells can be seen on all the stops, showing that to this day, they are visited, tended and cared for.

You can find more information on the self-guided tour here.

Have a story idea or tip in Brooklyn? Email Hannah by CLICKING HERE.