Brooklyn Mental Health Court addressing mental illness in criminal justice system

NEW YORK -- The subway chokehold death of Jordan Neely has put a spotlight on mental illness in the criminal justice system.

Neely was a subway performer who had dozens of prior arrests. His family has said he struggled with depression and schizophrenia and getting help.

CBS New York's Lisa Rozner took a closer look at a Brooklyn program that mandates treatment instead of jail.

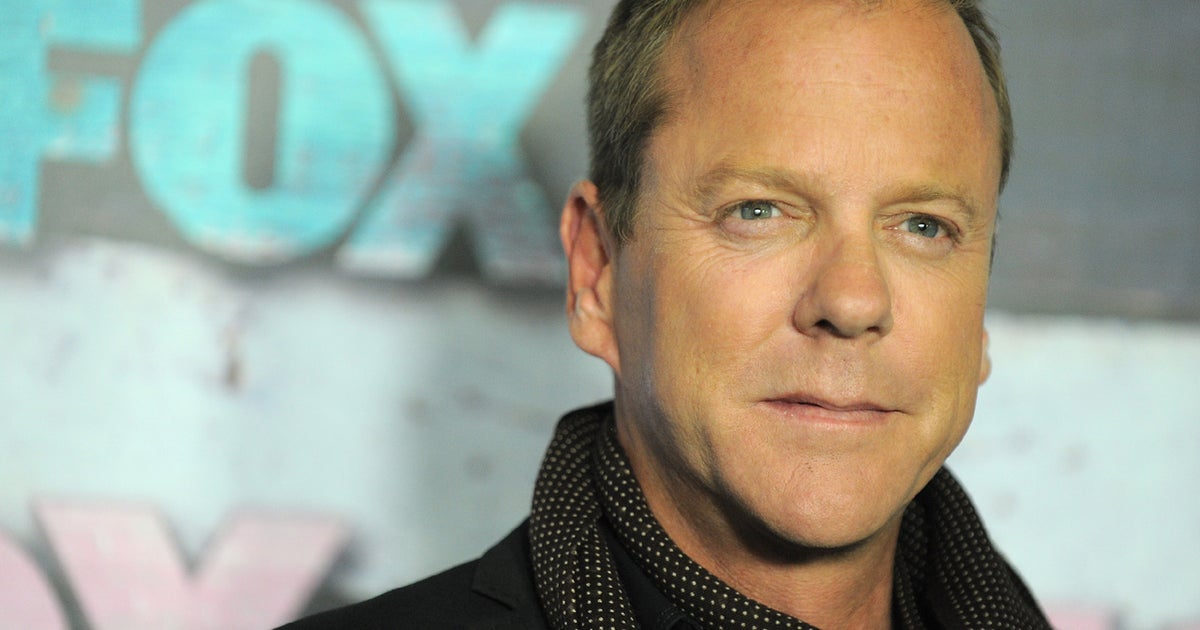

Inside Brooklyn Mental Health Court, presiding judge, Hon. Matthew D'Emic, sits among decorations, a warm touch that he says helps contribute to establishing a relationship with each participant, which is paramount.

"If you do that, then, like any relationship, you don't want to disappoint each other," said Judge D'Emic.

The court was created in 2002 to provide treatment, instead of jail time, for people with serious mental illness who committed nonviolent crimes.

"A lot of times, it's the mental illness that is behind the crime," said Kendrick. "And so if we can get people back on track and get them in treatment, then we can stop that cycle."

Organizers say to date, more than 1,000 mentally ill adults have successfully been diverted from incarceration to treatment.

There are several steps to how it works.

First, a defense attorney and district attorney must agree to refer a case to mental health court.

Then, evaluations are done by a social worker and a psychiatrist, which includes a risk assessment.

Third, if the defendant is shown to live with a serious mental illness and is not a public safety risk, then they are deemed eligible for the court.

Then, the district attorney and the defense attorney work out a plea deal that includes a potential prison term if the defendant fails the program.

At the same time, the clinical team develops a treatment plan.

In order to begin the treatment plan, the defendant has to first plead guilty to the charges.

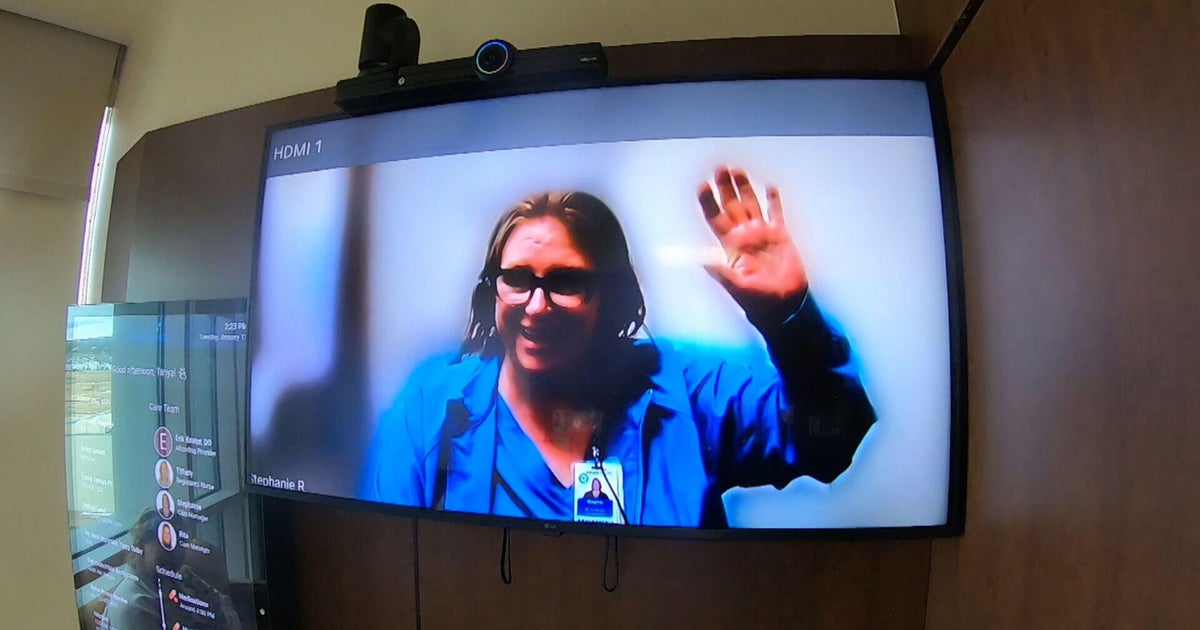

Project director, Ruth O'Sullivan, assigns a case manager.

"The case manager is responsible for making those referrals and scheduling the appointments," said O'Sullivan. "If you have someone with a serious substance use disorder who also has homelessness, then the appropriate placement would probably be a residential treatment program."

Rozner asked Judge D'Emic how the court ensures a defendant gets treatment but also doesn't cause further harm to anyone else.

"We have frequent court appearances, and I know that my clinical team stays in touch with the programs really on a daily basis," said D'Emic. "And I can bring the defendant into court, advance the case to the following day and talk to them."

The judge says all of the treatment programs are voluntary and he can issue a bench warrant if participants don't comply.

Every borough has a mental health court, but numbers from the Office of Court Administration show Brooklyn consistently has the most graduates.

For example, the judge says in 2022, there were 167 referrals. Out of those, 100 became participants and 82 graduated.

Criminal defense attorney Jonathan Fink says clients are typically in the program for at least one year.

"That can be expanded if, depending on how, how the client responds," said Fink. "They have phase one, the client will get a certificate."

Advocates say lack of affordable housing is a challenge as well as health insurance, which is needed for many treatment programs.

In 2019, the nonprofit Center for Court Innovation released a video highlighting a graduate of the program named Catrice.

"Before I came to Mental Health Court, my life was pretty much in shambles. I was homeless," said Catrice, who did not share her last name. "When I graduated Mental Health Court, my life was coming together. I got employment."

"I think there should be a Mental Health Court in every state, in every county because that's what we're seeing now, this uptick in mental illness," said Kendrick.

It is expanding.

New Hampshire recently became one of a growing number of states establishing statewide guidelines for mental health courts.