Broadcasters Keep Upper Hand In TV Disputes

LOS ANGELES (AP) -- A recent spate of TV blackouts and the lack of government intervention suggests that broadcasters have the upper hand over TV signal providers when it comes to negotiating fees, at least until Congress decides to act.

New York-area cable TV operator Cablevision Systems Corp. tested the limits of government intervention in October, calling early and often for the Federal Communications Commission to step in and force News Corp.'s Fox to keep providing its broadcast signal while it pressed for arbitration in a fee dispute.

Fox declined and the FCC did little more than suggest mediation if both parties were willing to participate. When the two sides couldn't reach a deal, Fox blacked out its signals to 3 million Cablevision subscribers for 15 days, through two games of baseball's World Series. On Saturday, Cablevision finally accepted terms it said were "unfair" for the sake of its customers.

Ultimately, the FCC said that its hands were tied.

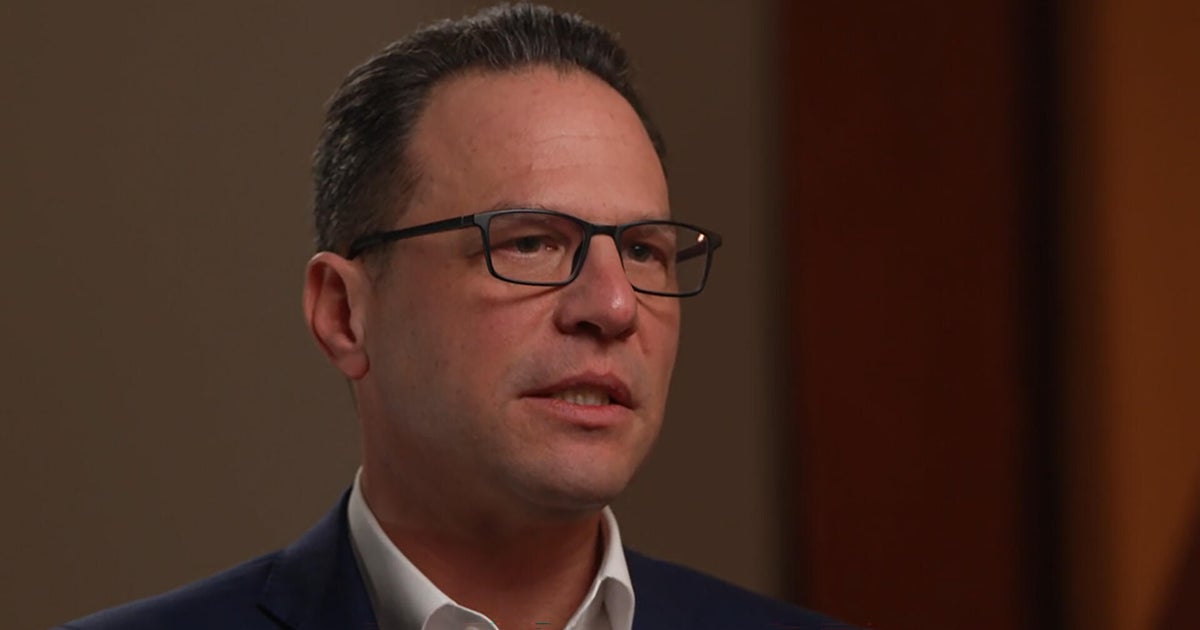

"Under the present system, the FCC has very few tools with which to protect consumers' interests," FCC Chairman Julius Genachowski said in a letter to Sen. John Kerry, D-Mass., in a letter Kerry's office released Friday. "Current law does not give the agency the tools necessary to prevent service disruptions."

Some analysts said Cablevision's move was mainly intended to draw the government out. Its battle had the support of other cable and satellite TV signal operators through such groups as the American Television Alliance, which counts Dish Network Corp. and DirecTV Inc. among its members.

Fox said in a statement Sunday that "this entire dispute was solely about Cablevision's misguided efforts to effect regulatory change to their benefit." Cablevision did not respond to a request for comment.

But the distributors are also competing with one another, rather than presenting a united front.

Dish Network announced Friday that it had settled its dispute with Fox, two days before Fox broadcast signals could have been blacked out to some of its 14.3 million subscribers. That would have made its service more attractive to Cablevision customers still stuck without Fox, and hurt Cablevision's position as the lone holdout.

It gave in just one day later.

Battles between TV signal providers and broadcasters have been raging for years and the latest dispute wasn't the longest.

In 2005, about 75,000 Cable One Inc. subscribers in Missouri, Louisiana and Texas went without signals from local NBC and ABC affiliate stations owned by Nexstar Broadcasting Group Inc. for almost the entire year.

In March, Cablevision also attempted a high-profile negotiating strategy and its customers lost their ABC station in New York in the hours leading up to the Oscars. Viewers missed the first 15 minutes of the awards show before Cablevision and The Walt Disney Co. reached a tentative deal.

The law at the center of the debates is the Cable Television Consumer Protection and Competition Act of 1992.

It allows broadcasters like Fox, ABC, CBS and NBC to choose between forcing a TV signal distributor like Cablevision to carry its local TV station, thus boosting its audience, or bargaining for the best rate it can for so-called "retransmission consent."

Because broadcasters bought the rights to such high-demand programming like football, baseball and the Oscars, they have chosen to bargain and have recently been pressing for higher fees.

The law heavily favors broadcasters in such negotiations because they have the ability to black out signals and subscribers are hard to win back if they switch TV signal providers.

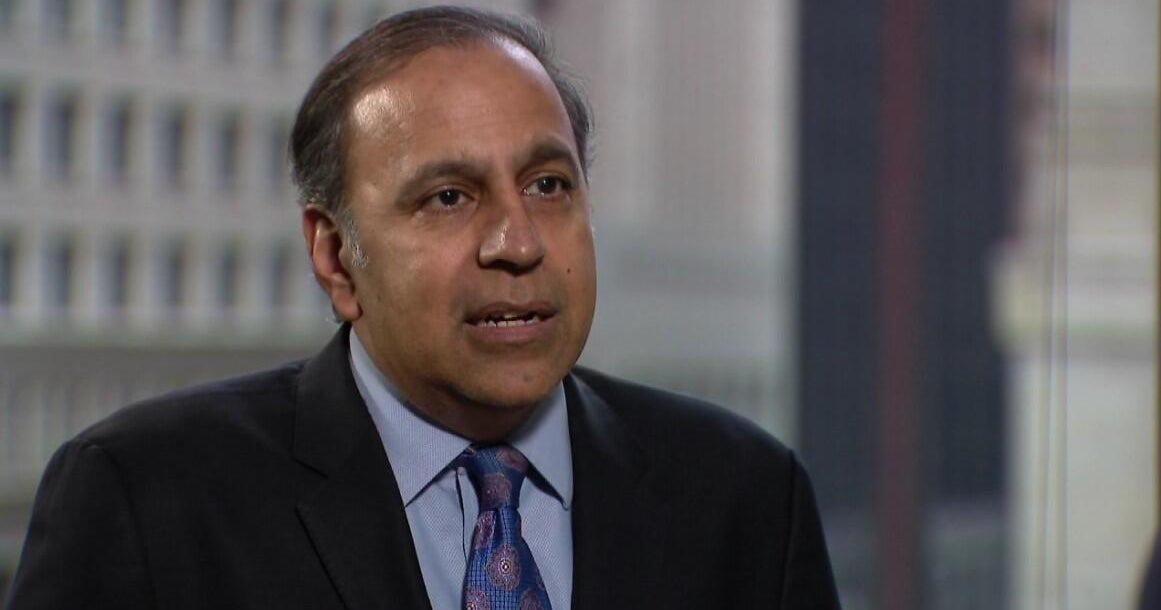

David Bank, an analyst with RBC Capital Markets, said it was in the best interests of the FCC to keep the balance tipped in broadcasters' favor. The FCC regulates the airwaves and it has authority over what broadcasters can send out over them. There are rules over obscenity and local content that don't apply to pay cable channels, which escape the FCC's grasp.

"That's what the FCC really cares about: minority voices on air, localism, childhood early education initiatives, obscenity," Bank said. If the balance of power were shifted to distributors, media giants could pull back from the broadcast model and move to an all-cable channel lineup. TV stations might disappear and the FCC would "lose the ability to regulate all that," Bank said.

The American Cable Association, a grouping of smaller cable operators representing 7.6 million subscribers, argued Sunday that the fight to change an 18-year-old law wasn't over and it said it remains within the FCC's powers to adopt regulations to prevent signal blackouts now. "Despite these deals being done, retransmission consent needs to change," its president Matthew Polka, said Sunday.

Both Genachowski and Sen. Kerry called for reforms of the current system. Genachowski, an appointee of President Barack Obama, said in his letter that "the current system relegates television viewers to pawns between companies battling over retransmission fees." Sen. Kerry called the existing regime "broken."

"Media interests have every right to play hardball," Sen. Kerry said in a statement Sunday. "But I believe it's incumbent upon those of us in public policy to see if there's a way to help protect consumers and avoid the now regularly scheduled, frequent games of high-stakes chicken that leave consumers in the crossfire."

(Copyright 2010 by The Associated Press. All Rights Reserved.)