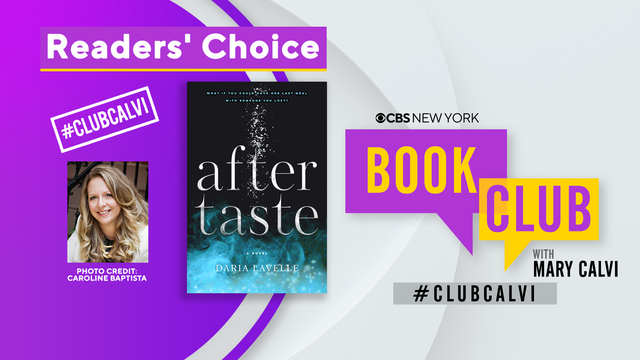

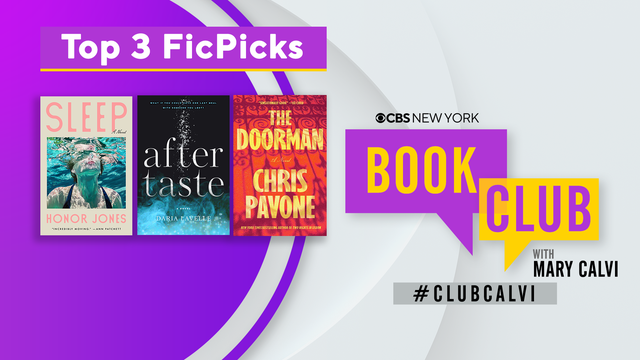

CBS New York Book Club with Mary Calvi's first choices revealed

EDITOR'S NOTE 3/12 6:10 p.m.: Voting has now closed. We look forward to revealing the winner Tuesday, March 14! Thanks for your interest in the Book Club with Mary Calvi. Please consider joining our Facebook group by CLICKING HERE.

Find out more about the books below.

CBS New York Book Club, you have spoken!

The CBS New York Book Club team has selected three fiction books. These "FicPicks" have plots and/or authors connected to New York, New Jersey, or Connecticut.

You've now had your opportunity to choose which book #ClubCalvi will read for the next month!

Below you will find information on our "FicPicks," including excerpts. One book is available to buy now. Two books are available for pre-order and will be released when we announce your selection on March 14. These books may contain adult themes.

Voting closed Sunday, March 12.

Prefer to listen? Audible has a 30-day free trial available right now.

"What Happened to Ruthy Ramirez" by Claire Jimenez

From the publisher: The Ramirez women of Staten Island orbit around absence. When thirteen-year-old middle child Ruthy disappeared after track practice without a trace, it left the family scarred and scrambling. One night, twelve years later, oldest sister Jessica spots a woman on her TV screen in Catfight, a raunchy reality show. She rushes to tell her younger sister, Nina: This woman's hair is dyed red, and she calls herself Ruby, but the beauty mark under her left eye is instantly recognizable. Could it be Ruthy, after all this time?

Claire Jiménez grew up in Brooklyn and Staten Island.

"What Happened to Ruthy Ramirez" by Claire Jimenez (hardcover), $23

"What Happened to Ruthy Ramirez" by Claire Jimenez (Kindle), $14

"A Likely Story" by Leigh McMullan Abramson

From the publisher: Growing up in the nineties in New York City as the only child of famous parents was both a blessing and a curse for Isabelle Manning. The only child of an iconic American novelist, she discovers a shocking tangle of family secrets that upends everything she thought she knew about her parents, her gilded childhood, and her own stalled writing career.

Leigh McMullan Abramson lives in New York City.

Note: Simon & Schuster is owned by CBS2's parent company Paramount.

"A Likely Story" by Leigh McMullan Abramson (hardcover), $23

"A Likely Story" by Leigh McMullan Abramson (Kindle), $15

"Take What You Need" by Idra Novey

From the publisher: Set in the Allegheny Mountains of Appalachia, Take What You Need traces the parallel lives of Jean and her beloved but estranged stepdaughter, Leah, who's sought a clean break from her rural childhood. In Leah's New York life with her young family, she's revealed little about Jean, how much she misses her stepmother's hard-won insights and joyful lack of inhibition. But with Jean's death, Leah must return to sort through what's been left behind.

Idra Novey teaches at Princeton University and in the MFA Program at New York University.

"Take What You Need" by Idra Novey (hardcover), $28

"Take What You Need" by Idra Novey (Kindle), $15

Excerpt: "What Happened to Ruthy Ramirez" by Claire Jimenez

If you drew a map of our family history, you might start it off with my dad, young, fat, and handsome, eighteen-year-old Eddie Ramirez, plotting to get with my moms, who was dark-skinned, small and freckled, long black curly hair. Freshly turned seventeen. Her name is Dolores. And you can probably start it off in Brooklyn. Canarsie. Draw a bump underneath my mother's wedding dress—that's Jessica. Then shortly after, in 1981, you can make Jessica a separate person, angry and red, pale-skinned like my dad, screaming in my mother's arms. Two years later draw Ruthy in pencil, lightly, because you're going to need to erase her in a couple of minutes. Now, draw the Verrazano, the water, the Island, the dump. Draw my proud family, Puerto Rican and loud, driving over the bridge and a little pink town house in West Brighton. I'm the one born in 1986, in Staten Island. They named me Nina. Make me look cute. The five of us seem normal for a while, up until Ruthy turns thirteen and disappears. Now you can rub her body away from the page. Draw my mother sixty-two pounds later. Give her diabetes. Kill my dad. Cut a hole in the middle of the timeline. Eliminate the canvas. Destroy any type of logic. There is no such thing now as a map.

Call that black hole, its negative space, the incredible disappearance of Ruthy Ramirez.

# # # #

First of all, if you really want to know what happened to Ruthy Ramirez, then you got to understand what happened that day at school. But maybe people don't really want to know what happened that day. Maybe people don't really care. Most adults already have their own ideas about the type of girl Ruthy is, that is because everybody's always running their mouths about her. And people like that, they're more interested in the type of little girl who one day rides her bike down her suburban block and disappears, only to show up later portrayed by some B actress on Unsolved Mysteries. Or they greedily watch the news, obsessed, as they guess who killed JonBenet Ramsey.

So what? Most people are followers anyway. They don't know how to form their own opinions but somehow still think that they're like special. That they are better than me. Inside their head, they think they got it all figured out, about who I am and what happened.

Whatever! Who cares?

Not me, I promise you.

I'll tell you that much.

Let them continue to play themselves.

I can tell my own damn story.

Maybe let's start the story this way: There is a girl. Her name is Ruthy Ramirez.

You are that girl.

You have two sisters.

You live on the north edge of Staten Island with your crazy moms, your sisters, and your dad in a little pink town house. And after you turn thirteen, nobody can control you.

The whole day since homeroom, Yesenia (your fake former best friend) is walking around school like she's never borrowed your lip gloss after track practice, like she ain't the only girl in eighth grade who hasn't gotten her period yet, and like you hadn't helped her lie to everyone to pretend that she did. You say to yourself, That's all right, though. See what happens. See if I care. Keep it up, while she acts like the two of you didn't used to sit together every day during lunch in sixth grade, reading the Say Anything section in YM, contemplating the various philosophical questions of sixth-grade girldom: Would you rather [s***] yourself in front of a boy you liked or unexpectedly bleed through your white skirt during Social Studies?

Which is worse: accidentally farting while laughing at a joke OR blowing snot out through your nose?

Then at lunch in the cafeteria, Yesenia, for no good reason at all, says some slick [s***] like "Oh, look at Ruthy's shirt," to this girl Angela Cruz (who by the way isn't even in the eighth grade). Still, Yesenia is stupid and trying to impress her. For what?

What is so special about Angela Cruz anyway? She can barely jump in during double Dutch without getting hit in her big forehead by the rope. Food clings to the rubber bands in her braces when she talks [s***]. And she's not even that pretty. I mean, maybe a little bit in the eyes. But not really, though.

In fact, you should know that there is nothing special about Angela, at all. That is, if you really want to know my opinion about it.

But this is the problem with Yesenia: she's always copying her homework or her hairstyle or her opinions from other girls, the type of person Ms. Ellen in Life Skills calls a follower. Someone too scared to make their decisions by themselves.

"You gotta be a leader," Ms. Ellen always says very proper while passing the cookies around the circle during Girl Talk and making references to the different outcast characters turned heroes in The Mighty Ducks, while the boys in the corner break out singing "We Are the Champions" like the real losers they are.

Now, in the cafeteria, you turn around and look straight back at Yesenia, the way her long hair makes her look a little bit like the Little Mermaid.

Your sister Jessica told you once, "If you're fighting, don't ever let no [b****] make you look away. You understand me?"

So, you shout at the table in Yesenia's direction, "Well, that's cool, then. Nobody wants to be your friend anyway. Stupid." But that sounds real little-girlish coming out of your mouth, so you imitate your moms and add "Pendeja," for good measure.

Unfortunately, though, class 802 steps into the cafeteria prematurely for lunch and the combination of their voices and bodies slamming against each other—their LA Lights slipping on the floor slick with the residue of spilled milk, their collective clowning on the dude with the messed-up fade—eclipses your voice, which leads to the following question: If a thirteen-year-old girl screams in the middle of a cafeteria but nobody hears her, does it really even matter?

The shirt in question, the one Yesenia rolled her eyes at, is a cropped halter top, almost identical to the one T-Boz wore when she was dancing on top of the ocean in the video for "Waterfalls," which is by far your favorite CrazySexyCool track (I mean, obviously). You bought the shirt yourself, off the three-dollar rack at G+G, while your mother was looking for size 8 wide flats for work at Payless. Not that you would ever actually admit aloud that you and your family shop at Payless, but, anyways, that's beside the point. Back to the story, you see: your moms with her rosaries and turtlenecks and unlimited statues of santos and orishas would probably kill you if she ever saw you wearing that crop top now, even underneath your overalls, whose straps you let dangle to reveal your perfect thirteen-year-old stomach.

Ugh, your mom loves you, but she's like . . .God. . .TOO MUCH.

For no reason at all.

Doesn't she even realize that there are girls literally giving head and smoking in the stairwells? Just because some stupid older girl dared them, and they were too afraid to say no.

Followers. All of them, just like Ms. Ellen says.

And all you do is go to track after school and get into fights sometimes, which really means you were just defending yourself. That's the real unfortunate tragedy of it all. In reality, you are the good girl, and nobody knows it.

But that's also besides the point.

Excerpted from What Happened to Ruthy Ramirez by Claire Jiménez. Copyright © 2023 by Claire Jiménez. Reprinted with permission of Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.

Excerpt: "A Likely Story" by Leigh McMullan Abramson

Prologue

New York, 1989

Claire stood with her back to the bar and surveyed the pulsating mass of people deeply pleased with themselves for being exactly where they were at exactly that moment. The party was an unqualified success. She kept being congratulated, as if it took genius to send invitations, rent out a restaurant—even a hot one like Gotham—and tell her florist, it's an avian theme, go wild. The maple branches growing out of birdcages were something, but Claire did not take pride in floral arrangements. As she and her husband had grown wealthy to the point of rich, Claire was wary of becoming one of those Upper East Side types who mistook purchased goods and services for accomplishment.

Claire had not read the book. As she nodded and smiled, agreeing with everyone about what a special, important novel it was, this secret blasphemy twinkled pleasantly inside her. Several yards away, the author was in the crowd, holding forth. The noise of the room was too loud for Claire to hear the specifics. After a decade of marriage, Claire couldn't imagine there was a subject she had not heard Ward expound upon, but she studied him still. By his theatrical gestures and exaggerated facial expressions, he was drunk.

"Can we get these at home, Mommy?"

Claire turned toward Isabelle, who was sitting cross-legged on a stool next to her. The bartender had given Isabelle open access to the tray of maraschino cherries, and she was now holding one aloft by the stem, swinging it talisman-like in front of her face. A viscous, chemical red dripped onto the smocking of her Laura Ashley dress.

"They're more of a special occasion treat."

Isabelle sighed. "I thought so." Isabelle had come with Claire to the hairdresser that day, and her daughter's blond tresses had been plaited and pinned on her head, threaded with baby's breath. The long evening had left Isabelle with loose strands and a halo of frizz. And after the cherries there was a subtle, almost clownish red ring around her mouth. Claire felt an ache of love for her only child.

"I took off my shoes," said Isabelle.

Claire looked down. "So you did."

Isabelle started to yawn, before stopping herself. "I don't feel tired at all." The plan had been to send Isabelle back uptown with a babysitter. But Isabelle had lobbied persuasively to stay. So it was the babysitter who'd left, and Isabelle who remained, now several hours past bedtime.

"Hmmm," said Claire, kissing her on her head.

"I think I should come to all your parties," said Isabelle.

"Oh do you?"

Isabelle was looking down, her fingers moving over the charm that hung from her neck on a delicate chain. "Don't you love my necklace?" she asked, thrusting forward the gold miniature replica of Ward's new book, custom-ordered at Tiffany's. God knows how much it had cost. Claire had not been consulted on the purchase.

"It's very nice."

Isabelle smiled and began to play with her mother's hair. A series of sharp pings broke through the noise. Ward's publicist was standing on one of the banquettes, tapping a knife on a champagne flute. Isabelle looked up.

"Daddy's going to talk now," whispered Claire.

Ward took the microphone and climbed onto the banquette, a move that elicited cheers from the audience. Ward raised his fist in triumph, before making a patting motion in the air, like a coach quieting his team. His newly graying hair sprang voluminously from his scalp in a wide circumference. He wore his signature red-framed glasses, cartoonish on anyone who wasn't arguably the hottest literary writer in America. It was becoming more and more difficult to

conceive of the before, the time when her husband had not been the Ward Manning. But not so many years ago, Ward was just another guy with a pile of pages, hustling a manuscript. Once upon a time, standing on a banquette wouldn't have gotten Ward applause; it would've gotten him fired. Now the lavish book parties, the award ceremonies, the inductions, the famous-people dinner soirées bled into one another. Yesterday evening, Nightingale Call had debuted at number one on the New York Times bestseller list. Whatever Ward published, people would read it. The number of authors—literary authors—who could do that was small indeed. People recognized him on the street, approached his table in restaurants. Ward was mythical, a god of letters. Just as Ward once promised her, he had become very famous.

Ward smiled without speaking for a long moment, reveling in the hushed anticipation.

"Two years ago, I started this book," Ward finally said. "I wanted to give myself a challenge." He paused.

"I decided I'd write about a guy who goes to live with the birds. Try making that not boring."

A big laugh.

Isabelle giggled. The profanity didn't seem to have registered. Like everyone else's in the room, her daughter's eyes had not moved from Ward. He went on to thank a list of people. Claire raised her glass and smiled when he said her name.

"And my daughter is here tonight."

Everyone turned to Isabelle and clapped. Isabelle blushed and put her hands over her face, which elicited a collective awwww.

"Come here, sweetheart," said Ward, beckoning.

Claire had not been alerted that Isabelle was to be part of the show, but she picked Isabelle off the stool. At seven years old, her daughter was almost too heavy for her, but not quite. Claire set her down and smoothed the back of Isabelle's dress before she took off toward her father. Ward, who'd stepped off the banquette, scooped her up and placed Isabelle on his shoulders. "Isn't she beautiful?" People whistled. Ward was blatantly using their daughter as a prop, manipulating the crowd with this heartwarming visual, as if he were father of the year. Claire looked at Isabelle, searching for the subtle signs of distress that only a mother would see. Instead she watched as Isabelle took the crowd on, bright-eyed, smiling coyly, her little stocking feet resting on Ward's chest.

Until that night, Claire was meticulous in shielding their daughter from her father's fame. And she'd believed that Isabelle was still oblivious. Ward was just her father. But seeing her child aloft at this grown-up party, Claire knew she had been kidding herself. Isabelle knew about her father. She understood what was happening in the room, and she understood the role she could play in it. Claire watched the two of them gamely mug for a photographer from the New York Post. For the first time, it was Claire who was on the outside.

When the applause subsided, Claire watched Ward put Isabelle down on the ground again. He was pulled away by his editor, leaving Isabelle alone. She was suddenly tiny in the sea of full-grown bodies. She looked up at adults carrying on their own conversations, no longer interested, as her smile fell and her brow creased slightly.

Claire bent down to pick up Isabelle's Mary Janes before pushing through the crowd. She took Isabelle's hand, put on her shoes, and, without bothering with goodbyes, led her out onto the street. In the taxi, Isabelle lay down with her head in Claire's lap and was quickly asleep. Claire gazed out the window, a roiling inside her.

Long ago, she had made peace with her bargain. She'd known what she was getting into. Going along with one version of the story, allowing certain truths to be hidden—it hadn't cost her much. Or so she'd thought. As she blessed the narrative, over and over, year after year, she had never anticipated how she would feel when it was her own daughter who believed in it. Claire longed now to undo what had been done, to make Isabelle understand what was left unsaid. But as she sat in the car, speeding up Park Avenue, Claire feared she was already too late.

Copyright © 2023 by Leigh McMullan Abramson. From the forthcoming book A LIKELY STORY by Leigh McMullan Abramson, to be published by Atria Books, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Printed by permission.

Excerpt: "Take What You Need" by Idra Novey

Leah

This morning, I read that repeating the name of the deceased can quiet the mind when grieving for a complicated person. My stepmother Jean was a complicated person. I've been reading all kinds of advice since hearing of her death. I didn't know that she'd begun to weld metal towers in her living room, towers so tall she needed a ladder to complete them. Apparently, that's how she died, slipping from one of the ladder's highest rungs.

Jean never left the town where she was born, and where I was also born, and where Jean became the closest version of a mother I've known. It's a town in the southern Allegheny mountains, which have been sinking for millions of years and resemble rolling hills now more than mountains. I know uttering Jean's name won't quiet my mind any more than saying the word mountain will stop these hills from sinking further.

My use of the word stepmother, while soothing, is wishful thinking, too. Jean left my father when I was ten and hasn't technically been my stepmother for decades. I've gone through phases of calling her up, seeking her contrarian take on things. Just as often, it's felt saner to stop all contact, and the last four years we've had none.

Despite this prolonged recent silence, she left her towers to me. I received the news from a man named Elliott, who claims he'd been living with Jean for some time. He was reluctant to elaborate on the phone, beyond explaining that he was at the hardware store when Jean fell from the ladder. He drove her to the hospital, he said, as soon as he found her unconscious on the floor.

I'm driving toward Jean's house now, trying to give this man the benefit of the doubt, to imagine him grieving for her as well. Early this morning, I rented a car near my building in Long Island City.

It takes hours to cross the tilled middle of Pennsylvania and I'm not alone in this compact rental car. I have a young son in the back seat and a husband sitting next to me who isn't from this country and has never driven into the Allegheny mountains before. I'd planned on bringing my family here at some point, once the country was less polarized, or after Jean wrote first, or after I caved, and sent a few words to her. I work all day with words, revising them in multiple languages before they move on to websites, and yet these past four years I haven't been able to move even a single sentence in Jean's direction.

Beside me in the car, my husband, Gerardo, is sighing. The road before us has narrowed to two lanes, and for several miles, we've been trapped behind a blue pickup truck with several long plastic tubes rattling around in the back.

According to the GPS, it'll now be an additional twelve minutes until we reach Jean's driveway, and conjuring her name has yet to resolve the disquiet in my mind. Each time I say Jean's name to myself, I hear her even louder still, the rising pleasure in her voice when she read me fairy tales, stopping to insist that she wasn't like the stepmother in "Snow White," that she had no craving for my liver or my lungs.

All I want is to nibble at your heart, Leah, she'd tell me. You don't mind if I eat your heart sometimes, right? Just one of your ventricles?

I'd play along, tell Jean to eat my whole heart if she was hungry enough. We had such fun slipping bits of ourselves into the savage parts. I've yet to read any of those Grimm tales to my son. I've stuck to newer books for him, to stories that stir up nothing from my childhood and present no risk of Jean creeping into my voice. It's felt like a neat and necessary excision, leaving out Jean and the confusing appetites of those old tales. I'm fumbling enough already, ambling motherless into motherhood.

Except now there is no Jean. She's fallen to this odd fairy tale death while living with a man I know nothing about. I hope what Elliott said on the phone about her slipping from the ladder is true, and that Jean died in the rapture of making these towers. Maybe my grief will be easier to bear over these last few hills if I keep this fairy tale going in my mind. I know even fairy tales that bend toward mercy have their brutal twists, and there's no returning to these hills without allowing Jean to gnaw at my heart again, to chew on my ventricles like strips of venison.

In the back seat, my son, Silvestre, is restless and flailing his legs. I offer him the last of the apple slices I prepared for our long trip into these sinking mountains. I assure him this old truck with its rattling plastic tubes won't remain ahead of us forever.

Jean

I'd had it with the new mailman. He kept peering in at me through the screen door like I was up to something indecent. I was just trying to master the nature of a box. Everything I made was flat and six-sided, and I didn't need the new mailman snickering at any of it. I also couldn't keep the front door shut, not once the metal got molten enough to start releasing its fumes and the argon gas from the TIG torch was doing its inert magic to the air.

I tried to take the high road at first. I said please and called the new mailman by the name on his uniform. I said Kenny, could you please just leave the mail on the front steps, even if it's pouring? I told him I didn't care if my bills got soggy. Kenny said sure and then went on doing exactly what I'd asked him not to, creeping up to the screen door to spy on me.

When he got here yesterday, I was sawing the heads off a new batch of spoons. I used the spoon heads for the capsules I started brazing onto my boxes, to add a few lumps of surprise to the sides. I knew who at the flea market tended to have silver spoons. The silver ones were far softer to saw through than stainless steel. The real fun, though, was choosing what to place inside the spoon heads before I welded the capsules shut. I sealed all sorts of things inside—bits of photos, the buds of pine cones, whatever I damn well pleased.

Oh, I'd waited so long for these freeing days—too long to put up with Kenny's mocking face. When he snickered again at the screen door, I had to march out with my bow saw and let him know I'd slice off his goddamn nose if he came onto my porch again. With half this town packing heat when they went out for groceries, a threat with a saw seemed reasonable enough.

This morning, at the creak of somebody coming up the front steps, I grabbed my bow saw again from the workbench. I was ready to let that bastard think I meant it.

From Take What You Need by Idra Novey, to be published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2023 by Idra Novey.