"Zombie cicadas" infected with mind-controlling fungus return to West Virginia

Humans aren't the only ones susceptible to the psychedelic chemicals found in magic mushrooms. "Zombie cicadas" — under the influence of a parasitic fungus — have reemerged in West Virginia to infect their friends, and now scientists have a better understanding of how it happens.

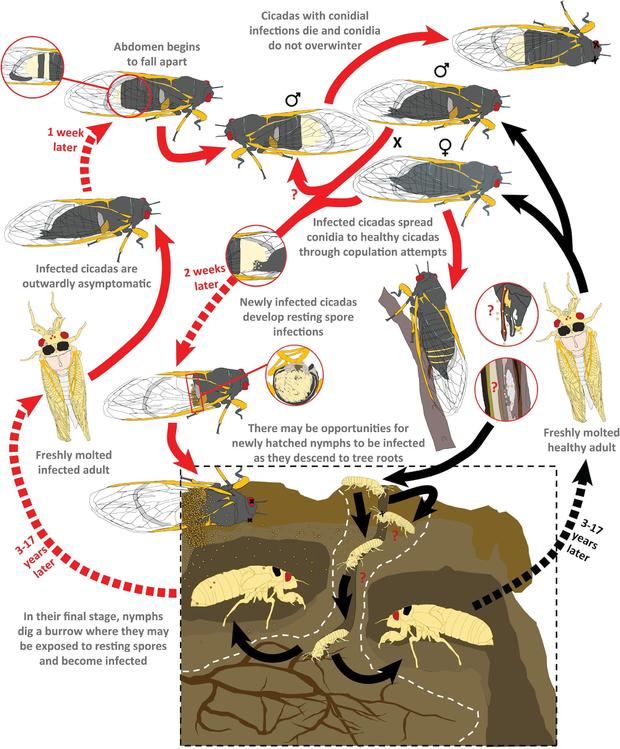

Researchers from West Virginia University recently saw the return of these bizarre creatures, which are infected with a fungus called Massospora. According to a study published in the journal PLOS Pathogens, the fungus manipulates the insects to unknowingly infect other cicadas, rapidly transmitting the disease to create a zombie army of sorts.

When a male cicada is infected with Massospora, researchers found it flicks its wings like a female, a known mating call. This behavior attracts healthy male cicadas, facilitating the spread of the fungus, which contains chemicals including psilocybin, found in hallucinogenic mushrooms.

Just how the disease manipulates its host and spreads is just the most recent discovery following decades of research on Massospora. The findings show the parasite functions, in part, as a sexually transmitted infection.

"Essentially, the cicadas are luring others into becoming infected because their healthy counterparts are interested in mating," co-author Brian Lovett, a post-doctoral researcher with the Davis College of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Design, said in a press release this week. "The bioactive compounds may manipulate the insect to stay awake and continue to transmit the pathogen for longer."

The team researched infected cicadas that returned to southeastern West Virginia earlier this year. While periodical cicadas only come out every 13 or 17 years, the timing is staggered in different locations, making it easier for researchers to study their behaviors.

Researchers described the gruesome details of the fungus' process as a "disturbing display of B-horror movie proportions." The spores eat away at the genitalia, butts and abdomens of the cicadas until they eventually fall off, replacing them with fungal spores — a brutal process for the insects, which just spent more than a decade underground.

The cicadas begin to decay, but rather than immediately die, they fly around and infect others. Because of the infection's mind-controlling abilities, the insects appear to behave as if nothing is wrong.

Lovett described the process as wearing "away like an eraser on a pencil." The fungi are similar to rabies — both "enlist living insects to do their bidding," researchers said — in a process called active host transmission, which is a form of "biological puppetry."

"Since we are also animals like insects, we like to think we have complete control over our decisions and we take our free will for granted," Lovett said. "But when these pathogens infect cicadas, it's very clear that the pathogen is pulling the behavioral levers of the cicada to cause it to do things which are not in the interest of the cicada but is very much in the interest of the pathogen."

Lovett and his co-author, Matthew Kasson, an associate professor of plant pathology and mycology, first discovered the psychoactive compounds in cicadas infected with Massospora last year. But until now, it remained unclear how infection occurs.

Researchers are not sure when in their life cycle they encounter the fungi. It's possible that cicada nymphs could encounter Massospora before emerging from the ground after 17 years to molt into adults, or on their way underground, before feeding on roots for 17 years.

"The fungus could more or less lay in wait inside its host for the next 17 years until something awakens it, perhaps a hormone cue, where it possibly lays dormant and asymptomatic in its cicada host," Kasson said.

But, there's no need to be concerned about being infected by the zombies. Unlike murder hornets or mosquitoes, these zombie cicadas are generally harmless to humans, researchers said.

"They're very docile," Lovett said. "You can walk right up to one, pick it up to see if it has the fungus (a white to yellowish plug on its back end) and set it back down. They're not a major pest in any way. They're just a really interesting quirky insect that's developed a bizarre lifestyle."

Due to their relatively slow rate of reproduction, the fungus does not present a major threat to the cicada population overall. But scientists still hope to discover how the pathogen developed, and how it may be evolving to further terrorize other insect species.