Health officials: Here's what we need to do to stop Zika virus

New details about the possible effects of the Zika virus on the fetal brain emerged Wednesday as top U.S. health officials said mosquito eradication here and abroad is key to protect pregnant women until they can develop a vaccine.

The Obama administration has asked Congress for $1.8 billion in emergency funding to fight Zika.

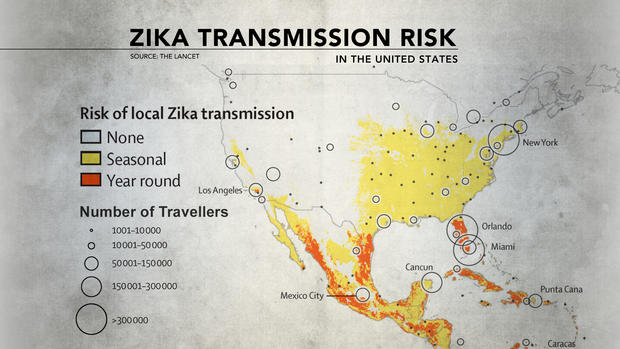

CDC Director Dr. Tom Frieden told a congressional committee on Wednesday that much of the effort must focused on mosquito control, especially in southern parts of the U.S. that harbor the mosquito that spreads the virus. Officials don't expect large outbreaks in the continental U.S., but have warned that there could be limited local transmission, small clusters, in those areas, like there have been of related viruses, dengue and chikungunya fever, which are carried by the same mosquito.

"There's the enemy," Frieden said, gesturing towards a large photograph of the Aedes aegypti mosquito. The species flourishes in hot weather and is active during daylight hours. "It can bite four or five people in the course of one blood meal, meaning it can spread disease quickly," he said.

Zika is spreading rapidly through much of Latin America, and Frieden warned that "we will likely see significant numbers of cases in Puerto Rico," based on how quickly chikungunya spread through that territory in 2014.

"We're working around the clock to find out as much as we can, as quickly as we can, to inform the public and to do everything we can do to reduce the risk to pregnant women," Frieden said.

At least 67 cases of Zika virus have been reported in the U.S. to date. All but one of the patients contracted the virus during travel overseas. There was one case of a person in Dallas becoming infected through sexual relations with a partner who had recently returned from Latin America.

To protect women of child-bearing age in Zika-stricken countries, developing a vaccine will be important. The virus "is a flash infection," disappearing from the mother's bloodstream in days, said Dr. Anthony Fauci of the National Institutes of Health. That means other ways of fighting maternal transmission likely wouldn't work.

He hopes small safety studies of an experimental vaccine might begin late this year, but said how long it would take to prove a candidate shot really worked depends in part on whether the Zika outbreak is still going on next year or burns itself out.

The CDC has issued a warning for pregnant women to avoid traveling to more than two dozen countries where Zika is currently spreading.

New evidence of brain damage

Also on Wednesday, European researchers reported new findings on the impact Zika can have on an unborn baby. The case study involved a fetus with an extremely abnormal brain -- not only a fraction of the proper size but lacking the usual crinkly neural folds -- whose mother suffered Zika symptoms at the end of the first trimester while she was living in Brazil.

Brazil has reported a surge in the number of babies born with unusually small heads, a defect called microcephaly that can signal underlying brain damage. Whether the mosquito-borne virus really causes microcephaly isn't yet proven, but Wednesday's report in The New England Journal of Medicine offers additional biologic clues.

"This fetus was really devastated," said Dr. Michael Greene of Massachusetts General Hospital who with colleagues from Harvard reviewed the findings in an accompanying editorial.

Second-trimester ultrasounds in Brazil didn't spot any problems but a third-trimester scan when the woman returned to Europe did. A post-abortion autopsy found the Zika virus in the fetus' brain but, remarkably, no other organs, reported researchers from the University of Ljubljana in Slovenia. They also genetically sequenced the virus, which could help further research into the suspected link.

Last month, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced finding Zika genetic material in brain tissue from two Brazilian babies who'd died, and in the placentas from two miscarriages.

Together, the findings offer important evidence but still, "there are more questions than there are answers at the moment," Greene said.