Righting wrongs: How Joyce Watkins was exonerated in court

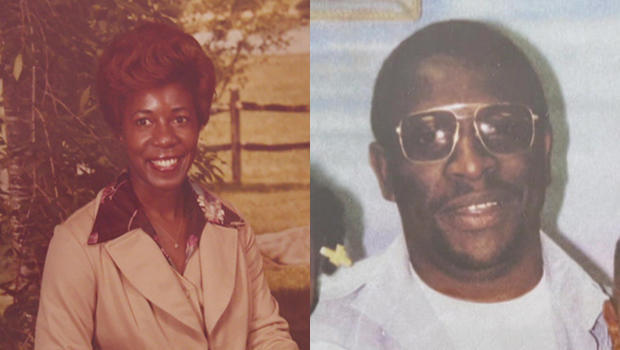

In 1988 Joyce Watkins and her boyfriend, Charlie Dunn, were wrongfully convicted of a terrible crime: the murder of Watkins' four-year-old great-niece, Brandi.

Watkins said, "It took everything away from us. It took us from our families, him from his kids. Took us from everything we worked for."

Dunn died in prison in 2015. But last December, in a Nashville, Tennessee courtroom, the 74-year old Watkins finally heard from the Davidson County District Attorney General Glenn Funk the words she had prayed for: "I want to say to both Ms. Watkins, and to the family of Charlie Dunn, that I believe they were actually innocent."

"I had been trying to get this done for a long time," Watkins told CBS News correspondent Erin Moriarty.

How long? "It took 35 years," she laughed. "I'm just not a person to give up. I knew there was somebody out there, somewhere, would help me."

Exonerations are rare, and this one might never have happened if not for an extraordinary partnership between attorneys who are usually on opposite sides: those who defend the accused, and the prosecutors who put them away.

District Attorney General Funk told Moriarty he is part of a growing number of prosecutors who believe they have to do more to uncover wrongful convictions – and to prevent future ones. "Our job is not to just seek convictions; our job is to seek to do justice," he said. "The goals have to be not only righting any past wrong.Then it's also, how did we get it wrong? Because we can't make that same mistake again going forward."

In 2015 Funk set up a Conviction Review Unit, and to show how serious he was, in 2020 Funk hired a lifelong defense attorney, Sunny Eaton, to run it,

"I think it would be fair to say that Glenn and I probably have more heated debates than he might have with anyone else in the office," said Eaton. "But I wouldn't be doing my job if that wasn't the case."

But there was little debate over the case of Joyce Watkins, brought to them by her defense attorneys at the Tennessee Innocence Project. Jason Gichner, the Project's senior attorney, said, "You need to spend all of two minutes with Joyce to realize that there is no way that this woman committed the crime she was convicted of doing. And it's not consistent with anything we know about Charlie or his family, either."

The couple's ordeal began late on the night of June 26, 1987, when a relative asked Watkins to come get her great-niece, Brandi, who had been staying with that family member in Kentucky for two months. Almost immediately, Watkins says she knew something was wrong with the child, and called Brandi's mother: "I said, 'Look, I'm fixing to take her to the hospital.' She said, 'Well, Joyce, we're on the way.'"

But by morning, when Brandi's mother (who lived seven hours away) hadn't arrived, Watkins took the child to the emergency room. The four-year-old (who was later transferred to Vanderbilt University Medical Center) was suffering from head and vaginal injuries. She died a day later.

Moriarty asked Watkins, "Did it occur to you at that moment that you would be accused of her death?"

"No."

"But they questioned you?"

"They asked me what happened to her. I told them I didn't know. I couldn't tell them something I didn't know, 'cause I don't know."

What she also didn't know is that the assistant medical examiner had mistakenly concluded that the child's injuries had occurred when she was at Watkins' house.

Gichner said, "Once that opinion came out, everybody just got laser-focused on Joyce and Charlie. It didn't matter that they cooperated with the investigation, that they kept meeting with the police over and over again without a lawyer and saying, 'We didn't do this. Come to the house, come take whatever evidence you want, photograph the scene.' It just didn't matter."

Moriarty asked, "When you heard at the hearing last December just how wrong her medical evidence was, how did you feel about that?"

"Broken," Watkins replied. "Broken. Real heartbroken."

Watkins believed that appellate courts would make it right. But the truth is, without compelling new evidence, it is difficult to get an appeal, let alone win one. Their appeals were all denied

Nathaniel Dunn, Charlie's oldest son, told Moriarty, "It just hurt from the heart, 'cause my daddy was doing time, hard time for something he didn't do."

"Did you visit him while he was in prison?"

"Yes, ma'am. It hurt going to see him, and it hurt when I left, you know, 'cause I had to leave him there and he couldn't come home with me. It hurt all over."

Web Extra: Joyce Watkins on what she lost because of a wrongful conviction:

In 2015, after Charlie Dunn died of cancer, Joyce Watkins was granted parole and released after 27 years in prison.

When asked what her mission was at that point, she replied, "To prove our innocence."

Determined to clear Dunn's name as well, Watkins was unable to do it on her own, and turned to the Tennessee Innocence Project. "It's a really tough road to prove that you are actually innocent through our current appeals process," said director Jessica Van Dyke.

Jason Gichner said, "If you're on your own trying to do this, and trying to get medical experts to help you, and trying to get back into court and litigate a complicated appellate process, doing that on your own is almost impossible."

And it takes time – time that Watkins didn't have. So, her defense attorneys did something that was once unimaginable: they went to the District Attorney's Office that once put the couple behind bars and asked for a new look at the case.

"There's nothing controversial, there's nothing political, there's nothing adversarial about it," said Gichner. "If there's evidence that these people are innocent, and went to prison for something that they didn't do, there doesn't need to be a fight about it. We should all be running to the courthouse as fast as we can to fix it."

Last fall, Sunny Eaton filed her report. Her conclusion: the wrong people were tried for Brandi's death. "We have so much information that these injuries happened before ever getting into Joyce and Charlie's custody," she said. "They were the only two people who sought help for this child."

Less than two months later, in front of a courtroom filled with Joyce Watkins and Charlie Dunn's family and friends, it was official. The judge announced: "Ms. Watkins, this charge against you is dismissed. And to the family of Charlie Dunn, the charge against Charlie Dunn is dismissed."

"It was a happy day. It was a happy day," said Watkins.

There are now conviction review units in 28 states.

But the process does not always run smoothly. Some state officials, fearing that reopening cases will clog courts, oppose any efforts to make it easier. Take what happened in St. Louis, Missouri. More than three years ago, the city's top prosecutor, Kim Gardner, found overwhelming evidence that Lamar Johnson, in prison for 27 years, was innocent of murder. But Missouri Attorney General Eric Schmitt continues to defend his conviction.

Johnson remains in a maximum security prison in Missouri. "What I'm struggling with," said Johnson, "is trying to understand why I have not been heard."

- Why are wrongly-convicted people still imprisoned in Missouri? ("Sunday Morning")

Funk said, "I do think it's offensive that some other court or Attorney General would try to intervene and keep someone in prison who the district attorney had properly investigated and determined to be innocent."

Moriarty asked, "What about all the DAs and State's Attorneys who say, 'We have to protect the integrity of convictions'?"

"Not if we have it wrong," said Eaton.

"Getting it wrong" in the case of Charlie Dunn and Joyce Watkins caused them to lose everything. She will still need a pardon from the governor to get any compensation.

And so far, there's been no justice for four-year-old Brandi. Whoever killed her is still free.

Moriarty asked Watkins, You never had time to grieve the loss of Brandi?"

"No, I haven't," she replied. "But I am gonna go and visit her grave."

For more info:

- Davidson County District Attorney's Office, Nashville

- Conviction Review Unit

- Tennessee Innocence Project, Nashville

- Joyce Watkins fundraiser (GoFundMe)

- Quattrone Center, University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School, Philadelphia

Story produced by Sari Aviv. Editor: Carol Ross.