What are executive actions?

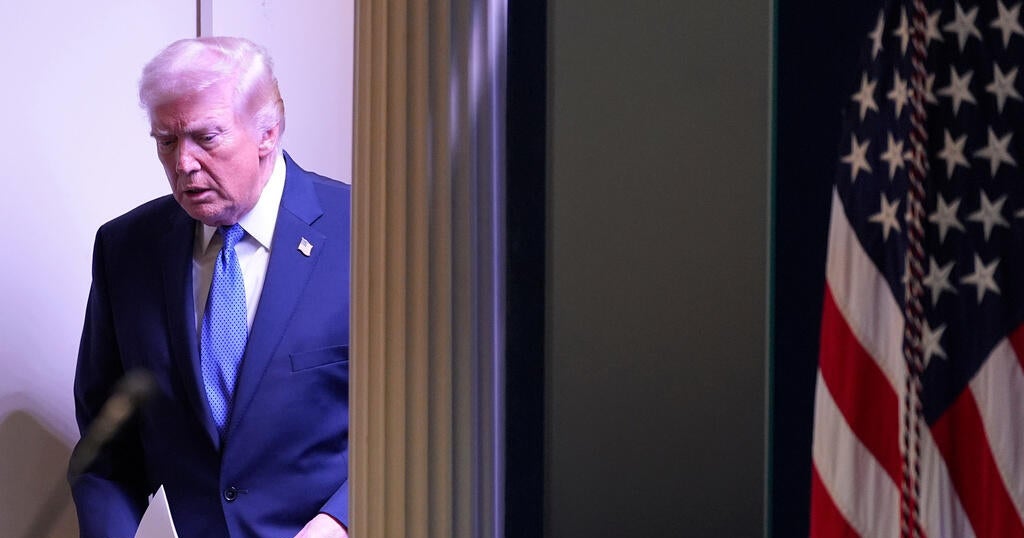

During his first week in office, President Donald Trump has been busy exercising his presidential pen. He has signed a series of executive actions ranging from slowing the implementation of Obamacare to fulfilling his campaign promise of building a wall along the southern border with Mexico.

But what exactly are executive actions? And just how meaningful are these actions taken by President Trump?

Executive actions get their power from Article II of the Constitution. There are a number of different edicts that fall under this category—from presidential proclamations to presidential directives-- but the two most important are executive orders and presidential memoranda.

Executive orders carry the greatest weight. “It’s a document that orders the executive branch officials to do something,” as Saikrishna Prakash, a law professor at the University of Virginia puts it.

So far Trump has signed four executive orders (President Obama had signed 279 by the time he was done). These orders are required by law to be recorded in the Federal Register and archived which means there is always a binding document recording the action.

The Constitution grants Congress the power to write legislation, executive orders are the president’s tool to implement lasting and meaningful policy within the powers granted to a president in the Constitution. For instance, Harry Truman’s Executive Order 9981 integrated the armed forces and John Kennedy’s Executive Order 10925 created the requirement that government contractors had to implement affirmative action policies.

If a president issues an executive orders telling federal agencies to act outside of the powers given to the executive branch in the Constitution it is meaningless. One of Obama’s first acts as president was to sign an order closing the military prison Guantanamo Bay, something he campaigned heavily on in the 2008 election, but without congressional approval it was unenforceable. Congress refused to authorize the transfer of inmates to U.S. soil and the prison remains open today.

Presidential memoranda are next on the hierarchical ladder. Due to the blurred nature of their use and power they have been called “executive orders by another name” The president uses this tool to state the administration’s position on a more general scope of policy. John Hudak of the Brookings Institute notes an advantage presidents have of using presidential memorandums over executive orders is, “they [executive orders] have taken on such a pejorative connotation.” This “pejorative connotation” stems from the fear of presidents abusing their power by going around congress to implement their own laws. In the public eye and in an increasingly political atmosphere, presidential memoranda sound less harmful than executive orders.

Memorandums act as proposals to persuade, rather than order bureaucracies to move in a certain direction. So far President Trump has issued eight memorandums ranging from removing the U.S. from the Trans- Pacific Partnership (TPP) to instituting a hiring freeze within the federal government.

The distinctions between these presidential edicts are blurry and the Constitution does not give them any formal definition. Although presidents have historically relied on executive orders, President Obama and (so far in his first week) President Trump have used presidential memoranda to cast their influence over specific policies. Both actions have a binding effect on the entire executive branch.

Dr. Lara Brown Associate Professor and Interim Director of the George Washington University School of Political Management sees a political motive in the growth of all this presidential paper. “Presidents have promised more and more,” she says “and have not been any more successful working with congress.” Brown says because of this, presidents have sought to do more on their own.

So what is the significance of Trump’s executive actions so far? Congress still has the “power of the purse” and it would take their action to implement some of what Trump lays out in his orders and memoranda. For example, while President Trump can sign an executive order telling his agencies and departments to begin the construction of a wall, it is up to congress to appropriate the funds necessary for the wall to actually be built. Unlike Obama’s failure to close Gitmo, Trump has a congress willing to work with him.

Cristina Rodriguez a law professor at Yale, says it’s important not to get too caught up on the particular edicts a president uses, but to focus on “what actually gets done.” This will be Mr. Trump’s test as he continues to push his large political agenda and trying to rally members in congress to enact the proposals he has put forward.