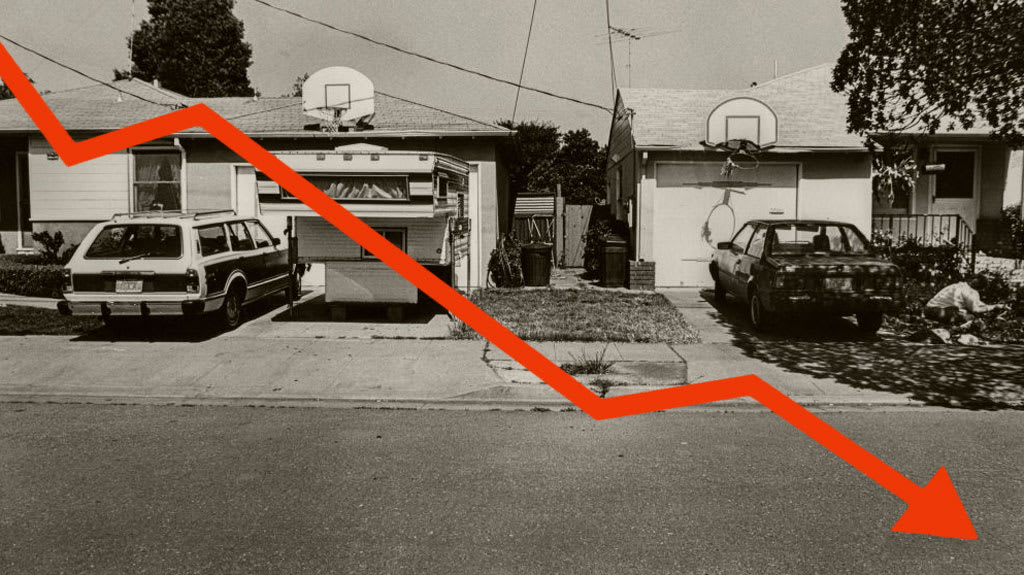

The worst states for workers have something in common: They're all in the South

Labor Day is a federal holiday to mark the achievements of the American worker — but not all workers are treated equally across the states. In fact, workers in some U.S. states fare poorly when it comes to pay and access to sick leave and other protections, according to a new analysis from anti-poverty nonprofit Oxfam America.

In the past several years, states have stepped in to create new worker protections and boost their minimum wages amid a lack of policy changes at the federal level. For instance, the federal minimum wage has been mired at $7.25 an hour since 2009, prompting more than half of U.S. states to raise their own baseline wages in recent years.

Some states have also added laws on paid sick time and family leave, as the U.S. remains the only developed nation without such guarantees for its workers. That means the treatment that workers experience is increasingly determined by their state, ranging from how much they earn to whether they can take a sick day without risking losing pay or even their job.

"The country is becoming a patchwork where where you live determines whether you are protected at work and if you can have a family," Oxfam researcher Kaitlyn Henderson told CBS MoneyWatch. "The difference between the top and bottom states are notable."

The worst states for workers have a few things in common, including that they are clustered in the Southeast, with North Carolina scoring the lowest. The following three lowest-ranked states are Mississippi, Georgia and Alabama, the new study found.

The analysis based its rankings on three main issues: wages, worker protections (such as paid family leave) and the right to organize.

Overall, the Southeast is the worst region for America's workers, Oxfam said. The best section of the U.S. for workers is the West Coast, with Oregon taking the top spot for its treatment of workers.

Better treatment, better outcomes

The analysis also looked at the correlation between states' treatment of workers and outcomes such as food insecurity, poverty and infant mortality levels. It found that there were "persistent relationships" between these measures of well-being and the state rankings for workers.

For instance, with every 10-point increase in Oxfam's rankings, the federal poverty level dropped by 0.4 percentage points. Similar relationships were found between food insecurity and child mortality.

"The connection between these labor-focused policies are very strong to other measures of well-being like food insecurity, poverty and child mortality," Henderson said. "The truth is, if you aren't looking out for the well-being of the people who live in your state, that's not a good investment."

To be sure, many workers have flocked to states such as Texas and Georgia, especially during the pandemic. But Americans who are able to telecommute and have white-collar jobs have different experiences than low-wage workers, who may be earning the minimum wage without the benefit of paid sick days or other protections.

"One of the things we learned in the pandemic is mobility can be a privilege, and there are a lot of people who weren't able to relocate for more space or better air," Henderson noted. "If we invest in the workers who are vulnerable, to lift them and make their lives better, then it makes everyone's lives better."