Small towns use financial incentives to lure young, educated workers back home

In our series Work In Progress, a partnership with professional networking site LinkedIn, we explore the future of jobs and issues facing the American workforce. In this installment, we look at a program that aims to lure college-educated workers back to their home towns.

Federal statistics show the unemployment rate, which currently sits at 3.9 percent, reached a 17-year low in April. For many people, the chance to leave home, go away to school and establish a career someplace new is part of the American dream, but for employers in those hometowns, watching the potential workforce walk away can be painful. Some places are doing their best to coax people back home and they're willing to pay money to do it.

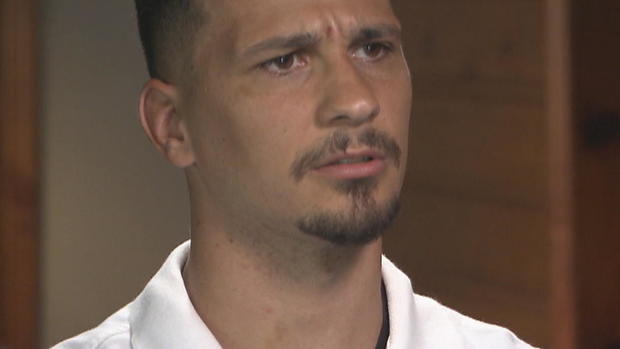

After being away from home for college and graduate school, Aaron Skinner is moving back to eastern Michigan. But that wasn't his original plan.

"I was really looking at either staying in Atlanta or Grand Rapids," Skinner told CBS News' Don Dahler. "The east side of Michigan was kind of down low on my list."

Skinner just received his chiropractic degree in Atlanta, but behind that smile and sense of accomplishment lies a mountain of student loan debt close to $300,000 – or a "very nice house on the beach" as Skinner put it.

So he jumped when he found out that his home county – St. Clair, Michigan – would pay him to move home and help him with his student loans.

"They're investing a lot of money into me, so I'm looking to invest that back into the community and either set up a practice or work out of another practice."

Skinner is taking advantage of St. Clair's Come Home Award – offered to college-educated people who grew up here and left – to lure them back to the county. Skinner will get up to $15,000 toward his student loans just to return.

It's a deal Kayla Parzynski couldn't pass up. Her $10,000 scholarship paid off her undergraduate loans, which helped her buy her first house.

"It was a great opportunity financially. It took a big load off of me. And I think it's worth it," Parzynski said. "I can definitely see myself here for a long time."

St. Clair County, a picturesque collection of small towns and cities, runs along Lake Huron and the St. Clair River. It's a quiet region with plenty of small-town appeal. The average annual salary there is just under $52,000, slightly more than the national average.

Randy Maiers helped create the Come Home Award and works with local businesses and organizations to help fund it to reverse a brain-drain from the area.

"I think a part of it is that the young people that grow up here, they get a chance to leave after high school and go to college and they want to get away from small-town America. I mean, you know, I can't blame them. The lure of Detroit or Chicago nearby, or the Carolinas. It draws people away," Maiers said.

Less than 18 percent of St. Clair's 160,000 residents have a college degree. Compare that with nearby Washtenaw County – home to University of Michigan – where more than half have a college degree.

It's not a jobs problem. LinkedIn editor-at-large Chip Cutter says the issue is educated and trained workers.

"So we're seeing this real trend across the U.S. where places like New York or San Francisco or Boston, these cities that just keep attracting the type of educated workers that employers crave. It's kind of a rich-get-richer situation," Cutter said.

It's why incentive programs are popping up around counties, towns and small cities across America: places like Crawford County, Ohio; Grant County, Indiana; and the small town of Marne, Iowa.

"It tends to be more of a gradual problem where over time workers leave, they don't necessarily come back, a town loses its population and then the companies that are there say, 'We're having a really tough time finding workers.' It might not be as dramatic as the Hollywood story, but it's just as urgent," Cutter said.

St. Clair has had 45 applicants for the Come Home Award since the program began in 2016. They have awarded them to 10 people, which doesn't sound like a lot, but Randy Maiers said that even a few people coming back, planting roots and starting families, can make a difference.