Women and children make up majority of asylum-seekers sent to Guatemala under Trump deal

Women and children make up a majority of the nearly 400 asylum-seekers the Trump administration has shipped to Guatemala since it began implementing a controversial agreement with that Central American nation.

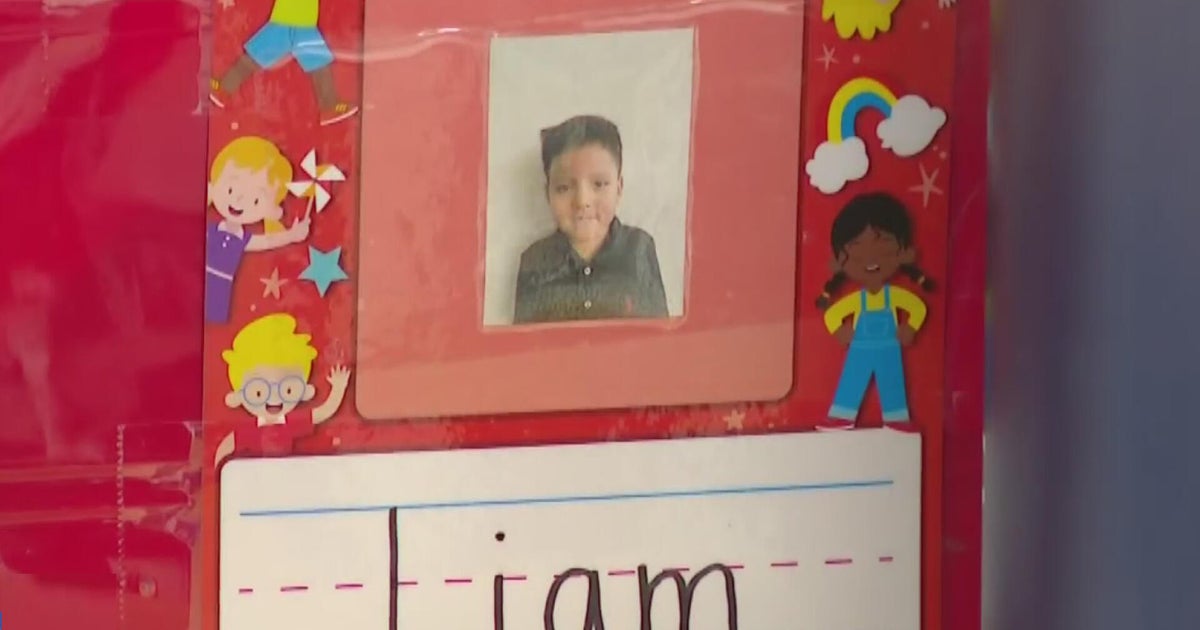

As of Tuesday, U.S. immigration officials have sent 378 asylum-seeking migrants from Honduras and El Salvador to Guatemala, denying them the opportunity to request refuge in the U.S. and forcing them to choose between returning home or seeking protection in Guatemala. Those deported under the deal include 144 children, 136 women and 98 men, according to the Guatemalan government.

Many of the asylum-seekers are part of families since unaccompanied migrant minors are exempt from the agreement, meaning that all the children have been deported to Guatemala with at least one parent. However, the exact number of families rerouted there by the U.S. is unclear.

With deportations under the deal ramping up in recent weeks, advocates worry about Guatemala's ability to continue receiving large numbers of families with children.

"It is very clear that Guatemala is not prepared to accept hundreds of families, which is why the vast majority of families have chosen essentially to return to their home country," Aaron Reichlin-Melnick, policy counsel at the American Immigration Council, told CBS News, citing a statement in which the United Nations refugee agency said asylum-seekers could face "life-threatening dangers" in Guatemala.

According to the Guatemalan government's migration institute, the country is currently processing roughly a dozen cases of asylum-seekers who have requested protection in Guatemala after being deported there by the U.S. The rest have chosen to request help returning home.

U.S. officials began enforcing the agreement, one of several policies the administration has used to restrict access to asylum at the southern border, last November. The deal is one of three "Asylum Cooperative Agreements" the U.S. forged with all countries in Central America's Northern Triangle, and the only deal to have taken effect so far.

Under the agreement, certain migrants who seek protection at the U.S.-Mexico border can be denied the opportunity to do so by Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officials. Those designated as eligible are interviewed by an asylum officer while detained in secure CBP facilities, which lawyers are barred from. If the migrants fail to prove they are "more likely than not" to face persecution in Guatemala, they are sent there within days since the decision by asylum officers can't be reviewed by an immigration judge.

So far, U.S. officials have subjected Honduran and Salvadoran migrants to the agreement, and have not moved forward with a controversial plan to send Mexican asylum-seekers to Guatemala, a proposal that drew objections from Mexico's government.

The Department of Homeland Security did not respond to a series of questions, including one on whether the agreement's stated objectives are undermined by the fact that few of those subjected to it have chosen to seek refuge in Guatemala. The department has portrayed the agreements as a way to ensure that migrants fleeing persecution can obtain protection closer to their homes.

But the deal has been met with strong criticism from immigrant advocates, who say Guatemala, a country with a skeletal asylum system that has seen an exodus of hundreds of thousands of its own citizens in the past two years because of extreme poverty and endemic violence, should not be in the business of offering foreigners safe haven.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and other groups have already filed a lawsuit seeking to halt the agreement's implementation.