Will the immigration debate affect the Hispanic vote?

As the Senate's "gang of eight" announces its proposed immigration bill, the political calculus behind any bipartisan push seems clear. Immigration affects many groups but after winning a whopping seven in 10 Hispanic votes last year, Democrats will particularly want to fulfill a promise to tackle it, while Republicans need to start winning some of those voters back. Many will see this as a chance for the GOP to re-engage after finding themselves on the wrong side of a demographic wave that could hinder them in elections for years.

Last cycle it seemed Republicans couldn't get a hearing from Hispanics after the strident talk of fences and deportation that had surfaced during the primaries. The party's own post-election review lamented that - and Mitt Romney's "self-deportation" comment in particular: "If Hispanic Americans perceive that a GOP nominee or candidate does not want them in the United States they will not pay attention to our next sentence."

What we'll see, though, that the debate has to go through a Congress where the growing impact of the Hispanic vote hasn't yet proven as determinative at the legislative level as on the presidential map. And as an issue, immigration looks like only a first step - perhaps as much a language and branding test as a policy matter - in finding out whether Republicans can win back Hispanic voters -- Because the data make clear it's economic policy, and ultimately an economic message, that will matter.

What's At Stake: The Politics of the Hispanic Vote

In the wake of the 2012 presidential election, "demographics" became shorthand explanation for President Obama's win. One big part of it was the double-whammy of immense margins in the Hispanic vote shifting toward the Democrats, coupled with the growth of the group. Going forward, there are plenty of reasons short- and long-term to watch how Hispanic vote considerations do (or don't) play into the political calculus of immigration reform now.

Big picture, the percent of voters who identify as Hispanic has risen to 10 percent and increased steadily over the years. Democrats won 71 percent last year, 67 percent in 2008 and 53 percent in 2004.

The Electoral College impact is biggest and freshest in everyone's minds. (Considering how some whispered 2016 contenders are involved in this effort, there's at least some current news peg here for looking at the presidential map.) The southwest, except for Arizona - and even that could soon get interesting but it's another story - has gone blue for at least two straight cycles.

The table below shows how much of Mr. Obama's total vote came from Hispanic voters in critical "battleground" states in Colorado, Nevada and Florida. You'll see that at least one in five of Obama's votes there came from Hispanic/Latino voters and the racewide margin between him and Mitt Romney was far smaller. Without that kind of support from the Hispanic vote Mr. Obama would have lost all three.

In Colorado, Nevada and Florida, Mr. Obama drew at least one in five of his total votes from Hispanic voters. That proportion was far larger than his win margins in each state, which were in the single digits.

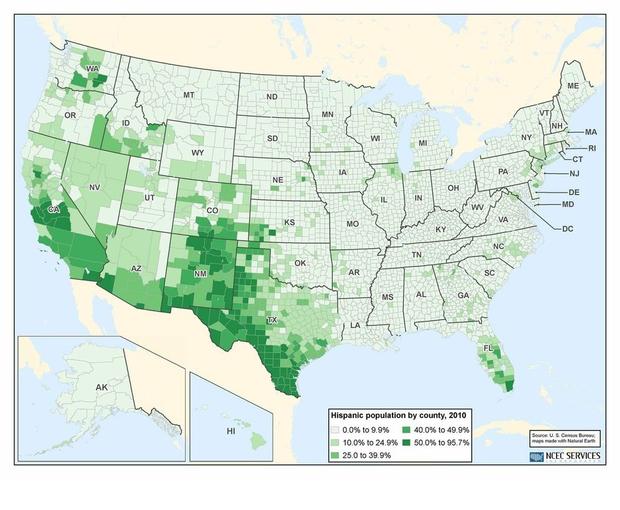

When you look at the map of Hispanic population as a percentage of county populace, the first thing that catches your eye is in that southwest and in Florida. But there's even more to the story. Look a little closer and you'll see some slightly greener pockets, not as dramatic as in the southwest but there, in northern Virginia, in North Carolina, a couple of spots in Iowa. (Battleground states!)

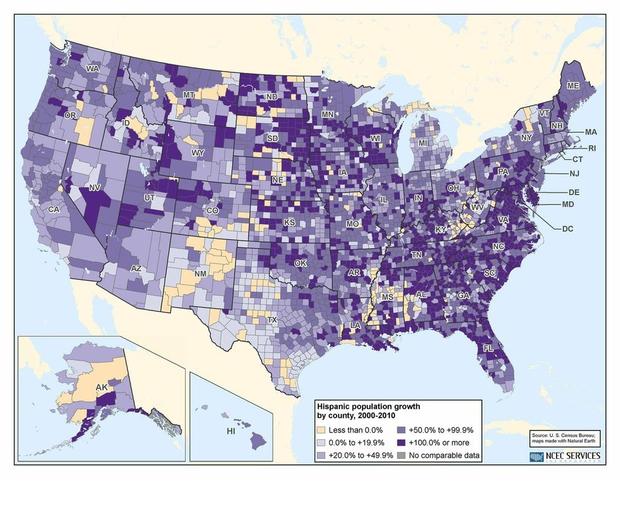

Now here's a map of Hispanic growth by county. You'll see the more highlighted, faster-growing regions in all those other states like North Carolina, Virginia, Iowa, and the overall pattern heavier in the east and south. Look, especially, at that boom in Florida, and along the southern part of the east coast and the midwest, too.

Now, large percent jumps can still mean very small numerical populations. But the trend is notable, and sometimes can be important if we were talking about voting in a close race. Also, not everyone described on these maps votes. In fact many don't. Many are too young yet, some aren't eligible or aren't engaged. But they might eventually, and that too is part of the trend.

Some of this is starting to materialize already. Consider: Virginia, with at least 25 percent Hispanic growth in some northern counties from 2000 to 2010, was five percent Hispanic voters in 2012, with a two-to-one margin for Obama, accounting for a comperably higher share of his statewide total than his win margin.

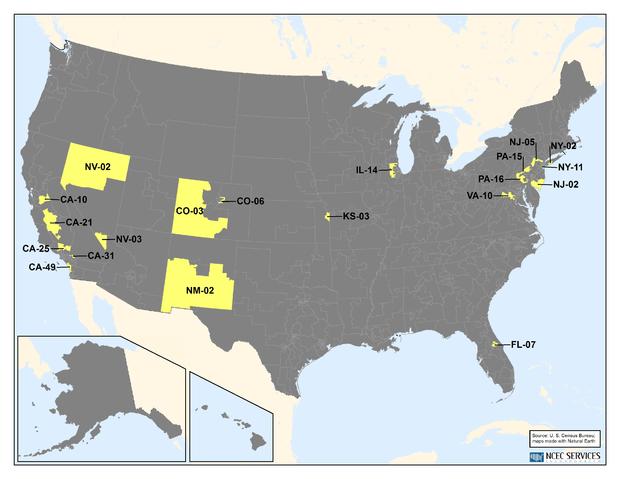

Eventually any reform bill is going to have to go through the House, so let's look at the Hispanic vote there next - where it has a much more limited impact in terms of swing or electoral impact. Simply put, the Republican House majority doesn't really need the Hispanic vote to retain control. Here's why:

By districting designs that involve both parties, and the legal needs of representation, Republicans tend to represent districts that have fewer Hispanics (other than Cuban-Americans) and are majority white, while majority-minority districts, including heavily Hispanic districts, tend to be Democratic, and very strongly Democratic at that.

Republican-held congressional seats have on average 10 percent Hispanic population while Democratic-held seats have twice that at 21 percent.

(In fact, the 10 percent average percent Hispanic across Republican-held House districts is deceptive, as a handful of them, including largely Cuban-American districts, pull that average high; the median Hispanic percentage of GOP held districts is 6 percent.)

The result is that the nation's Hispanic vote is highly represented within the Democratic caucus, and there is only so much swing or leverage, not the way it might be in, say, a Presidential race with a few battlegrounds.

In a lot of Republican districts that do have a substantial portion Hispanic, the Hispanic vote is not really a "swing" vote that needs to be courted for them to win. Most of these districts are safely Republican even assuming that Hispanics vote heavily Democratic. The map shows that there are a handful of GOP-held House districts with a sizeable Hispanic population and which might profile as potentially competitive - but not many.

Of 76 Republican-held districts that have more than 10 percent Hispanic population, only seven have a partisan index (our measure of competitiveness from past vote patterns) that is roughly even between the parties. The average partisan rating of those is a large GOP +9 percent, meaning we'd expect a Republican to win by nine points over a majority, 59-41 percent, in most cases.

When the House takes up immigration reform, GOP members might well be thinking about the party and the broader political calculus as well as, of course, of the nation's policy needs. But there is less electoral incentive for them in syncing with Hispanic voters on immigration policy (or other policy) since that isn't needed to hang on to their individual seats. At least not right now.

Next page: Can the GOP win Hispanic votes?

The Long Term: Can the GOP Win Hispanic Votes?

There's evidence that Hispanic voters haven't deserted the GOP simply because of immigration stances, but rather because they simply found more favor with Democrats on the economy. We can see this is a couple of matters of ideology and views on the economic system, which are important because they describe more broad philisophical outlook than singular vote choice.

Most Hispanic voters in 2012 said government should in principle do more, not less - much the way Democrats overall did. (Importantly, though, if you're looking for places Republicans can win back some voters, Hispanics were 11 points less likely to say this than Democrats.)

Asked whether the U.S. economic system favored the wealthy or treated everyone fairly, Hispanics also profiled more similarly to the Democrats than Republicans in this regard - each believing it favored the wealthy - 61 percent of Hispanics compared to 71 percent of Democrats and 33 percent of Republicans.

Next look at party identification, another great indicator. The good news if you're a Democrat, is that most Hispanics (53 percent) called themselves Democrats. Foremost targets for Republicans, though, might be the 22 percent of Hispanics who called themselves Independents. Hispanics' partisanship rate is nothing like, for comparison's sake, the overwhelming partisan attachment expressed by African-American voters.

(Worth noting thought that Hispanic independents voted overwhelmingly for Mr. Obama, too, in almost the same proportion as Hispanics overall.)

And there wasn't much last year that connected Hispanics' priorities to those of Republicans. For instance Hispanic voters were a lot less likely to name "the deficit" as their top issue. Hispanics named the economy as their number one issue, as it was overall for everyone.

And in household income, too, Hispanic voters looked like Democrats. Half earned less than $50,000 in household income; just like a similar 49 percent of all Democrats did. Among Hispanics who voted for President Obama, 61 percent earned less than $50,000; that was higher than the 48 percent of all voters who backed him, and similar to the African-Americans who did (60 percent.)

For a final point, let's look specifically at views on immigration and compare it to economics. The former simply didn't seem to determine vote choice. About eight in ten Democratic voters nationally supported some kind of legal status for immigrants; 77 percent of Hispanics did as well. Moreover, Hispanics who favored legal status for undocumented immigrants (which was most of them, but not all) were not much more likely to vote for Obama than Hispanics in general. If this was just about immigration policy, one might have expected a more divergent pattern.

A majority of all voters in 2012 - not just Hispanics - favored the idea of allowing some legalized status to undocumented immigrants. That includes a majority of Republican voters, which further suggests there may be a electoral rationale for compromise on policy.

All of which says that when we think about the Hispanic vote and Republican prospects, economic messages will be the real test (in the parlance of the GOP report, it would be the message that comes in the "next sentence") and immigration is only the start, albeit an important one; a shot at reversing a cycle that got away from them. "There's got to be an economic and jobs agenda with outcomes that matter to Hispanic voters," said David Winston, a prominent Republican pollster. "Looking back on the 2010 House elections Republicans did comparably better with Hispanics on a message asking 'where are the jobs.' In 2012 Republicans saw a drop when they let statements that weren't reflective of the party's policies define things."

Brett Blythe (maps), Brian Fraher and Mark Gersh contributed to this report