Will Social Security run out of money?

(MoneyWatch) Social Security is not in financial trouble, at least not under the current laws that govern the retirement program. That's the unequivocal answer from Steve Goss, chief actuary for the Social Security Administration, who spoke recently about Social Security's funding challenges at the annual meeting of the Society of Actuaries in San Diego.

But what about all the headlines about the Social Security Trust Fund will run out of money in 2033? Goss explained that Social Security benefits that are paid each year to retirees and beneficiaries are primarily funded from two sources -- payroll taxes collected from workers each year, and the Social Security Trust Fund. Of these two sources, payroll taxes shoulder most of the burden, making Social Security primarily a pay-as-you-go system.

- Why Social Security is critical to our future

- Does Congress raid Social Security?

- What you need to know about Social Security

Even if Congress doesn't act to prevent the Social Security Trust Fund from running dry in a future year, there will still be workers paying taxes into the system, and those taxes will fund the benefits that are due to retirees and beneficiaries.

Social Security is not legally permitted to borrow money, so there are no sources of funding other than current taxes and the Trust Fund. Consequently, if the Trust Fund runs dry, under the law benefit payments must be reduced to the level that can be sustained by tax receipts in a given year.

If taxes in a given year exceed benefit payments, then the surplus is added to the Trust Fund. Likewise, if taxes fall short of benefit payments due for the year, the Trust Fund makes up the difference -- until it runs dry. For many years Social Security operated with a surplus, building up the Trust Fund to about $2.7 trillion as of the beginning of 2013.

Because future taxes are projected to fall short of benefit payments, Goss and his actuarial team project that the combined Social Security Trust fund will run dry in 2033. At that time, benefits to retirees and other beneficiaries in that year would need to be reduced by about 23 percent in aggregate. While that certainly isn't good news, it doesn't mean that Social Security will totally run out of money and won't be able to pay any benefits.

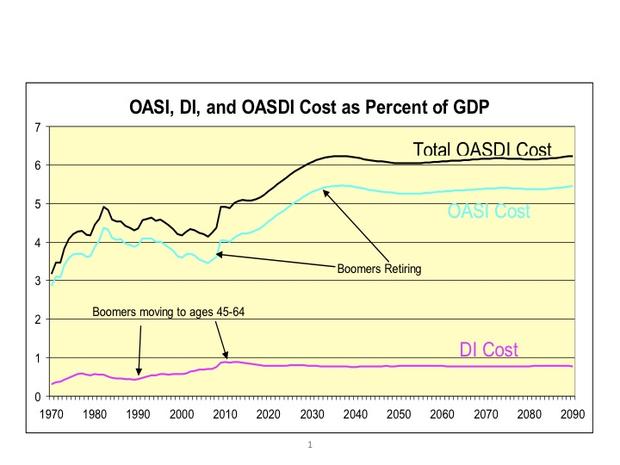

The problem is that projected taxes after the trust reserves are fully depleted in 2033 are estimated to fall short of projected benefits by 23 percent. The chart below from Goss's presentation illustrates this challenge. It shows Social Security benefits and taxes paid each year since 2005, expressed as a percentage of total earnings subject to payroll tax by the system, plus a projection to the year 2090.

After 2033, payroll taxes are projected to fall short of projected benefits. The top line in the graph below shows benefits after 2033 that are scheduled under current law but are not fully payable if the Trust Fund runs dry. The bottom line shows the reduced level of benefits that would be payable if the Trust Fund runs dry and nothing is done to address our funding challenges. In this case, the benefits paid out must balance with income -- the taxes paid by workers into the system -- and benefits would need to be reduced in order to match income.

After 2030, taxes paid into the system are projected to be about 4.7 percent of GDP, but the benefits paid will be about 6.1 percent of GDP. To close this gap, either taxes need to be increased by about one-third, benefits need to be reduced by about one-fourth, or there needs to be some equivalent combination of revenue increases and benefit reductions.

The fix is easy to say, and harder for lawmakers to make. We need to reallocate about 1.5 percent of all the goods and services produced by our country. This doesn't seem like an insurmountable problem. And the sooner our leaders make the necessary changes, the better we'll be able to adjust our plans accordingly and get on with life.