Will Donald Trump's two Steves clash over banks?

Will the tale of two Steves end in warfare within the Trump administration over how to regulate banks? President-elect Donald Trump has tapped two men for powerful posts whose approaches to Wall Street are poles apart: populist firebrand Steve Bannon and establishment Republican Steve Mnuchin.

In a way, the two men embody the two views of Wall Street that Mr. Trump displayed on the campaign trail -- that it’s an elite cabal that has hosed the average American, and a vital business that needs to be rescued from strangling government rules.

The firebrand, Bannon, will be Mr. Trump’s chief strategist in the White House, an enormously powerful post. Although Bannon once worked for Goldman Sachs (GS), he since has joined the GOP’s populist wing, which is suspicious of what he has called “crony capitalism.” He opposed the bank bailouts during the 2008 financial crisis. Bannon headed the right-wing website Breitbart News, which specializes in trashing the Republican leadership, and he has railed against the party’s establishment wing as “globalists” and “the party of Davos.”

A rumpled, unshaven fellow with a fiery temperament, Bannon, 63, endeared himself to Mr. Trump by taking over management of the campaign when it was floundering and refocusing the candidate on his all-out assault against the economic status quo.

The establishment Republican, Treasury Secretary-designate Steven Mnuchin, is also a Goldman alumnus, but he has stayed more in the storied investment firm’s buttoned-down mode. At Goldman, where he was a partner, Mnuchin ran the mortgage-backed securities trading desk and served as the firm’s chief information officer. He also has been a hedge fund operator and a bank CEO who aggressively foreclosed on delinquent mortgage borrowers -- making him a villain to both the populist left and right.

Soft-spoken and reserved, Mnuchin, 53, was the Trump campaign’s national finance chairman and raised tens of millions in small contributions. But while a lifelong Republican, he is hardly a movement conservative, having in the past donated money to Democratic politicians, including Hillary Clinton.

Of course, every administration has factions vying to get their way on policy and win over the president. And there’s no evidence to date of any conflict between the two. “They have always worked well together and are totally in sync with President-elect Trump,” spokeswoman Hope Hicks wrote in an email reply to questions about how Bannon and Mnuchin would interact.

Nevertheless, their pronounced differences have led to rampant speculation that they will end up tussling over policy. The stakes are high enough that the subject bears scrutiny.

“It’s populism versus Goldman Sachs,” said Mike Mayo, banking analyst at international investment firm CLSA. “Looks like there will be some mud-wrestling in the process.”

To Paul Brace, a Rice University political science professor who has studied the presidency, ”Bannon is genetically programmed to be a bomb thrower, and this could upset Mnuchin.”

In a research note, Cowen & Co. analyst Jaret Seiberg pointed out that Mnuchin probably will have his hands full on Capitol Hill revamping the tax code, with the result that “Bannon may play a bigger role on bank policy.”

Whose views are more likely to prevail on the banks question? Economist Hugh Johnson, who runs an asset management firm in Albany, New York, opts for Mnuchin. “Over time, I think Trump will learn to appreciate the more thoughtful and balanced approach” of Mnuchin, he said. “Trump cannot be a flamethrower and be successful, so my guess is that Bannon will become less important over time.”

The two incoming Trump officials have widely contrasting upbringings. Although both are wealthy, Bannon came from a blue-collar background and is self-made -- his father was a telephone lineman. Mnuchin’s father, Robert, was a Goldman lifer, and young Steve had a privileged upbringing. He drove a Porsche while a Yale undergrad.

Bannon served as a Navy officer, and his daughter went to West Point. He has expressed resentment at how few well-off types join the armed forces. Mnuchin, like many from his social stratum, didn’t serve in the military. Bannon worked at Goldman for only four years, while Mnuchin did for 17.

At this early stage, before Mr. Trump takes office, the public has seen only glimpses of Bannon’s and Mnuchin’s thoughts about what specifically they think needs to be done to reform Wall Street. While Bannon’s job isn’t subject to Senate approval, Mnuchin’s is, meaning he must testify before the Senate Banking Committee. That should shed more light on his intentions.

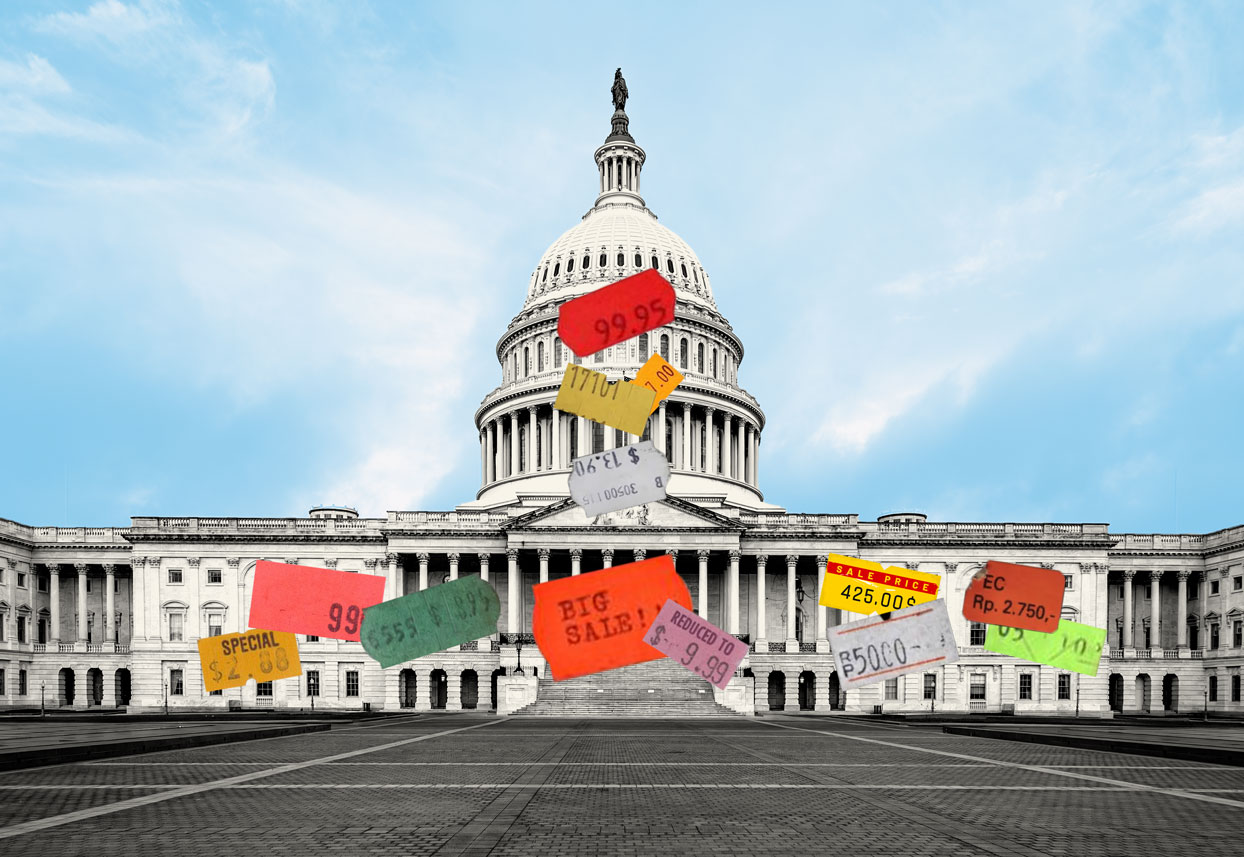

The Dodd-Frank financial overhaul law likely will be at the heart of their differences. Enacted in 2010, the measure requires banks to maintain sufficient capital to offset losses and curbs riskier trading using an institution’s own funds.

The law also set up the Consumer Financial Protection Board, which has cracked down on, among other things, what it sees as abusive lending and credit card schemes. Conservatives and the banking industry in general want to rein in the CFPB.

In recent TV interviews, Mnuchin has said he wants to pare back Dodd-Frank’s regulatory burden, especially on smaller banks, in a bid to encourage lending to businesses and consumers. He has indicated that the law’s rules were often “too complicated.” Note that he did not call for gutting Dodd-Frank.

Bannon hasn’t expressed his views on public issues lately, but in the past has been very vocal about Wall Street. At a conference held at the Vatican in 2014, Bannon railed against bailouts of banks during the 2008-09 financial crisis. According to a transcript of his remarks, he denigrated “the Republican establishment, which is really a collection of crony capitalists.”

He lamented that “no criminal charges” were brought against bank executives. And he warned: “Trust me -- they are going to be held accountable.”

Exactly what that might mean for bank rules is hard to tell. Bannon called for a restoration of something close to the Glass-Steagall Act, passed in the Great Depression and repealed in 1999. That law separated banks’ lending and investment operations, which Dodd-Frank mandates to a less-stringent degree.

Certainly, other actors are involved in this drama. Since the election, Vice President-elect Mike Pence, a former member of the House of Representatives, has been in close contact with congressional leaders to plot legislative strategy. Jeb Hensarling, Republican of Texas and the chairman of the House Financial Services Committee, has his own ideas on rolling back Dodd-Frank, and his panel has approved his version.

Ultimately, the White House’s policy will be shaped by Mr. Trump, who has indicated he wants to be a hands-on president who’ll negotiate with Capitol Hill, said economist Gary Shilling, who runs an investment firm in Springfield, New Jersey. Added Shilling: “What you’ll hear from the two Steves will largely be a reflection of what Trump thinks.”