Why you shouldn't worry about stocks slumping

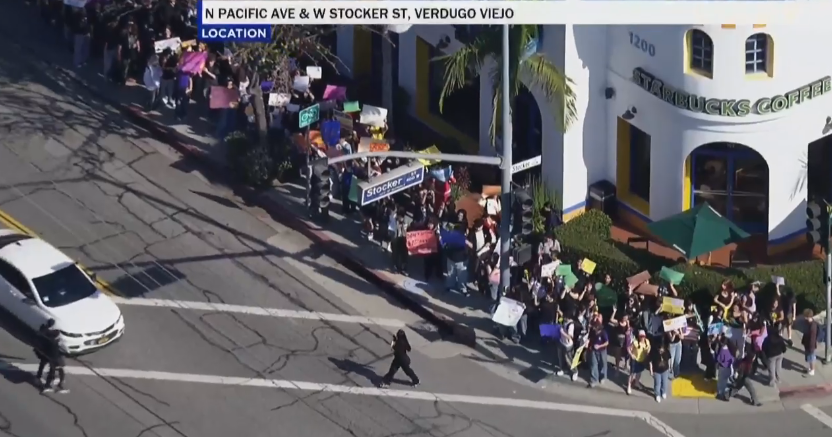

For Americans, blaring headlines about market "corrections" can cause plenty of agita given how rising equity prices are routinely equated with broader economic prosperity. President Trump, for example, has routinely pointed to the market's performance as evidence of his administration's good work. And to be fair, that thinking informs much of the media's coverage of stocks, with entire TV networks, newspapers and websites breathlessly following the daily gyrations of the Dow, S&P 500 and other indices of wealth.

But here's a reality check: What happens on Wall Street has much less impact on Main Street than people might think.

Taking stock

For one, most Americans don't own many -- or any -- stocks. Roughly 84 percent of the market's value is owned by the wealthiest 10 percent of income earners, according to research by New York University economist Edward Wolff, who included stocks held in retirement accounts in his analysis.

Put another way, roughly half of U.S. households own no stock, whether through a 401(k) account or shares in Apple (AAPL). And most of the remaining half of the population that do own stock have relatively little skin in the game. Most individuals and families had less than $5,000 in total holdings in 2016, the latest year studied by Wolff. He calculates that for nine of every 10 households, a market decline of 10 percent would at most have a 1 to 2 percent impact on the value of their holdings.

In fact, Wall Street's pain may be more acute overseas, by one accounting. That's because foreign investors own about 35 percent of all U.S. corporate stock, Steven Rosenthal, a senior fellow at the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, estimated in October.

Pay day at last?

Then there's what seems to be the main catalyst for the market plunge -- investor concerns that accelerating wage growth will lead to higher inflation and spur the Federal Reserve to jack up interest rates. Since most Americans' financial well-being depends on their paychecks, as well as homeownership, and wages in the U.S. have stagnated for the better part of four decades, a modest uptick in pay (which may or may not be sustained) is healthy for consumers and for the economy at large.

Finally, stocks just haven't fallen that much -- and this next part is key -- relative to the broader value of the market. The last time the Dow fell by a larger percentage in a single day was on August 8, 2011, when it shed 635 points to close at 10,810 points for a decline of 5.5 percent.

By comparison, the Dow fell 4.6 percent this week when it plunged 1,175 points on February 5 and another 4.2 percent when it slid 1,032 points three days later. As John Lynch, chief investment strategist for LPL Financial notes, none of these three seemingly scary drops ranks among the 100 biggest ever market declines in percentage terms.

Although the recent turbulence had equities down 10 percent from their highs, putting stocks in correction mode, that's still a ways off from the 20 percent decline that would signal a bear market. Meanwhile, unless you're a day trader, the market's day-to-day moves are unlikely to impact the longer-term health of your retirement account.

So while most Americans shouldn't be happy that stocks are in retreat, they also shouldn't worry too much.