Why the U.S. hasn't joined the race for deep sea mining in international waters

This is an updated version of a story first published on March 24, 2024. The original video can be viewed here.

Something akin to the California Gold Rush is happening in the Eastern Pacific—an international mad dash, not for one precious metal but for vast quantities of minerals scattered across the ocean floor—vital for everything from electric cars to defense systems. To avoid a free-for-all, 168 countries—including China—have signed onto the United Nations' Law of the Sea, a treaty that divvies up the international seabed. Conspicuously absent is the United States, kept out of the race by a group of Republican senators who say the treaty undermines American power. Despite efforts by five Presidents, ratifying the treaty has hit a wall in the Senate year after year. As we first reported in March, seabed mining is set to begin next year, and China is in place to dominate it. Now a group of former diplomats and military leaders is trying again to break the logjam in the Senate.

A thousand miles from U.S. waters—between Mexico and Hawaii—lies this patch of Pacific Ocean. It looks tranquil but it's a locus of fierce competition. To see what's at stake, you have to plunge to the bottom. See those potato-sized rocks? They're filled with cobalt, nickel, manganese and copper—some of the most valuable metals on earth.

In 2019, we went along on a pilot expedition as a crew with Canada's metals company hauled its sunken treasure to the surface.

Bill Whitaker: There are that many of them down there?

Geologist: If they found a deposit with this much metal concentration on land, it would be a bonanza that nobody would stop talking about for years.

Today, the race is on for the estimated trillions of dollars of strategic minerals on the ocean floor, vital for next-generation electronics. Countries that ratified the Law of the Sea treaty, now are testing giant robots that vacuum the minerals from the sea floor.

They're carving up and laying claim to parcels on the seabed covered with rich balls of ore. China has five sites—90,000 square miles—the most of any country. The United States? None: blocked from even putting a toe in the water by its refusal to ratify the treaty.

John Bellinger: We are not only not at the table but we're off the field. The United States probably has got the most to gain of any country in the world if it were party to the Law of the Sea Convention, and conversely, we actually probably have the most to lose by not being part of it.

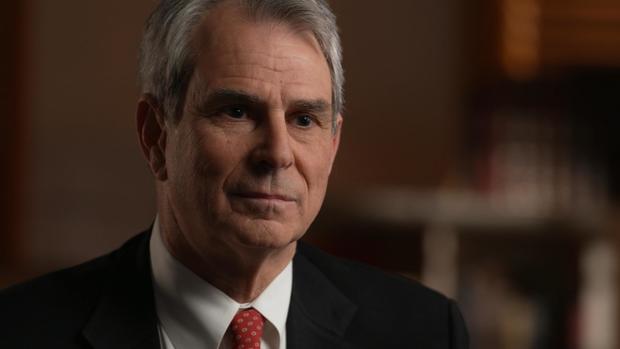

John Bellinger is a partner at the D.C. law firm Arnold and Porter. In 2012, he testified in favor of the treaty at Senate hearings as a former legal adviser to George W. Bush. He told us Bush was no fan of U.N. treaties but he supported this one, not only for codifying access to the deep seabed but also for safeguarding the free navigation of U.S. ships around the world. Bellinger told us support was so broad in 2012, he thought it would be a slam dunk.

Bill Whitaker: President George W. Bush was in favor

John Bellinger: That's right.

Bill Whitaker: U.S. Intelligence?

John Bellinger: Yes.

Bill Whitaker: Military?

John Bellinger: Yes.

Bill Whitaker: Major Business groups. Big Oil?

John Bellinger: Yes.

John Bellinger: And environmental groups as well. Hard to find any treaty or probably any piece of legislation that has such broad support.

Yet it failed. The conservative Heritage Foundation convinced 34 Republican senators to turn thumbs down, saying it would subjugate the United States to the U.N.

The law of the sea was sunk.

John Bellinger: It surprised me that a number of senators would tell us in the government, "We know better than you, uh we know better than our U.S. Military. We know better than U.S. Business."

Bill Whitaker: Does the American position make any sense to you?

John Bellinger: It honestly does not. The opposition was not on national security reasons or on uh business reasons. It to me seemed just a reflexive ideological opposition uh to joining the treaty.

Since 2012, while repeated attempts to ratify the treaty have failed, China has made deep sea mining a national priority. It already has a near monopoly of the critical minerals on land. Now, it's set to lock up the bounty on the sea floor. Ambassador John Negroponte—a former director of National Intelligence in the Bush administration—told us, China's aggressive actions should be setting off alarms.

Bill Whitaker: What's changed since 2012?

John Negroponte: The People's Republic of China and its more assertive behavior on the international scene, particularly in the South China Sea. And then with respect to deep seabed mining, they're eating our lunch. They've got access to five sites. Right now, we have access to none.

John Negroponte is one of a number of senior Republicans urging the Senate to reconsider and ratify the treaty. If it doesn't, the U.S. can't get a license from the U.N.-backed International Seabed Authority to mine the ocean bottom. It won't have a say in drafting environmental rules for mining the deep. Absent the U.S., China is the heavyweight in the room.

Bill Whitaker: So does it seem to you that we're just sort of giving this resource to the Chinese without any pushback from us?

John Negroponte: We are conceding. If we're not at the table and we're not members of the Seabed Authority, we're not gonna have a voice in writing the environmental guidelines for deep seabed mining. Well, who would you prefer to see writing those guidelines? The People's Republic of China or the United States of America?

Steven Groves: It just doesn't make sense to a conservative to say, "these minerals that are in the deep seabed are so important to the United States, we are done without those, let's put an international bureaucracy in charge of getting us access to them."

Steven Groves is a senior policy analyst at the Heritage Foundation. He was a special counsel in Donald Trump's White House. In 2012, Groves testified that the U.S. didn't need anyone's permission to mine the seabed. His views haven't changed.

Steven Groves: What businessman in their right mind said, "I'm going to invest tens of billions of dollars into a company that I will then have to go and ask permission from an international organization to engage in deep seabed mining?"

John Bellinger: But no general counsel, no board of a company uh, if faced with a clear right under a treaty that says, "You can go and do this" or taking an action that's flatly contrary to the treaty of course the companies are going to say, "I want to take the clearly lawful route before I invest billions of dollars."

Lawyer John Bellinger told us U.S. companies interested in mining the seabed want the legal guarantees of the treaty. But even as other countries move ahead, Steven Groves insists American companies are staying away—not because the U.S. hasn't ratified a treaty—but because deep sea mining isn't viable.

Steven Groves: If China wants to go and think that's it's economically feasible to drag those nodules up to the surface and process them, let them do it. The United States has decided to stay out of the game. The one U.S. company that had rights to the deep seabed got out of the game, that's Lockheed Martin.

Bill Whitaker: U.S. companies will tell you it's because there's uncertainty.

Steven Groves: What U.S. companies?

Bill Whitaker: Lockheed.

Steven Groves: Lockheed is out of the game.

Bill Whitaker: Lockheed will tell you that their investors—

Groves: Lockheed quit.

Whitaker: their—their counsel all say, "If we don't have this treaty, we're not—we're not getting into this."

Groves: They're already out of it. They quit.

Whitaker: Because we are not supporting them in any way.

Groves: Well that's a business decision they made.

Lockheed Martin has not quit. The defense giant had rights to four Pacific seabed sites. It sold two and is holding on to two in case the treaty passes. But Lockheed told us if the U.S. doesn't ratify the treaty, it can't dive in. Ambassador John Negroponte told us the Heritage Foundation is standing in the way.

John Negroponte: What Heritage is saying is we don't even want to give 'em a chance. We have—we know the answer already. And I, you know, I think that's sort of hypothetical thinking. The pragmatic approach would be to say, "Okay, let us have access and see what happens."

Bill Whitaker: And we could end up being even more dependent than we are today on China for access to these minerals?

John Negroponte: If they end up being the largest producer and we're not producing at all that might place us in a—in a difficult economic position.

But national security fears of China's growing prowess in the deep are about more than mining. In March, a letter signed by 346 former political, national security and military leaders, warned that China was taking advantage of America's absence from the treaty to pursue overall naval supremacy.

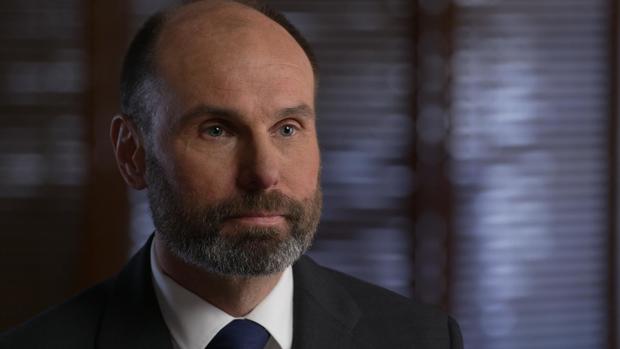

Thomas Shugart: Over the last decade and I've done the math, China has built 20% more warships by tonnage than the United States Navy has. They've built 160 warships, where the U.S. Navy built 66. It is a truly massive expansion in—in naval power.

Thomas Shugart is a former U.S. Navy submarine warfare officer and a senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security. He told us China is flexing its maritime muscle by claiming the South China Sea as its private ocean. It has challenged the treaty's navigation laws that ensure safe passage by harassing passing ships, including the U.S. Navy. It has fired water cannons at its neighbors, caused collisions, even flashed a military-grade laser at ships. Steven Groves at the Heritage Foundation says that's why the treaty is meaningless.

Steven Groves: It's China who is a party to the treaty who doesn't obey the rules of the road. They're the ones getting into near collisions with U.S. uh vessels in the South China Sea. The United States respects and adheres to international law. It is the Chinese who are the scofflaws here. And the idea that the U.S. joining the treaty would somehow change that Chinese behavior has no basis in reality.

Thomas Shugart: Every time the U.S. points at them and says, "You're violating the law," they very quickly turn back and say, "well you're not a signatory so what do you have to say about it?" We are in a messaging contest and an effort to win hearts and minds all over the world against what is clearly our greatest strategic competitor.

Former submarine Captain Thomas Shugart told us being outside the treaty undercuts American credibility, while China is laser focused on building its maritime power. He told us China's deep sea miners have a second mission: collecting information for the Chinese military.

Bill Whitaker: The technology that these companies use to mine the seabed, do they also have a military application?

Thomas Shugart: Absolutely. If you're going to find submarines in the ocean, you need to know what the bottom looks like. You need to know what the temperature is. You need to know what the salinity is. If China is using civilian vessels to sort of on the sly do those surveys, then that improves, could improve their ability to find U.S. and Allied submarines over time as they better understand that undersea environment.

Back in D.C., Ambassador Negroponte's group is lobbying the Republican holdouts. We decided to call the senators who torpedoed the treaty in 2012 to see if anything had changed. We found their opposition as strong as ever. With the U.S. Senate locked in stalemate, China is forging ahead.

Produced by Heather Abbott. Associate producer, LaCrai Scott. Broadcast associate, Mariah B. Campbell. Edited by Robert Zimet.