Why the market selloff could deepen

Stocks got hammered hard on Thursday in response to increasing nervousness following Wednesday more-hawkish-than-expected Federal Reserve policy statement. A looming debt default in Argentina, ongoing geopolitical hotspots and caution ahead of Friday's jobs report are all also playing a role.

Some of the corporate earnings news has also been mixed, with Exxon Mobil (XOM) reporting soft production. Consumer names Kellogg (K) and Colgate (CL) fell after both missed revenue expectations, while Kellogg cut fiscal 2014 guidance. Moreover, 3-D printing sweetheart 3D Systems (DDD) got crushed after missing top- and bottom-line expectations as inventories rose and margins fell.

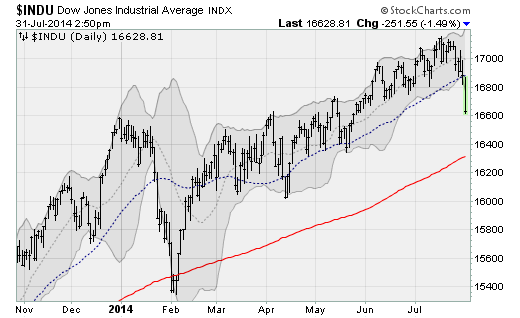

As a result, stocks suffered. The Dow Jones industrial average, closing down 317 points, has collapsed below a key indicator known as a lower Bollinger Band for the first time since January. But more than that, a flood of selling pressure hit the market -- washing away the investor complacency that had settled in over the last few months of easy, breezy gains.

You can see this in the way the breadth, or the number of stocks moving higher, collapsed today. In afternoon trading, there were more than 2,400 net declining issues on the NYSE. That's the worst reading since June 2013 and is deeper than the selling seen during January's emerging market sell-off and April's Russia-related worries.

But we're far from a deep oversold condition just yet.

For one, the percentage of S&P 500 stocks that are in uptrends has just fallen below 78 percent from a high of nearly 85 percent earlier this month. That matched the high set back in December before January's wipeout. When the market bottomed in February, this measure dropped to just under 62 percent. In April, it hit 65 percent.

The big plunge in 2011 featured a decline all the way down to 21.8 percent. So, whether this is just another light drop, or the start of something more severe, this suggests more stocks will need to be pushed lower first.

Valuations had also become quite extended. The cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings multiple on the S&P 500 had recently increased to levels that have only been exceeded during the bubble-blowing extremes seen in 1929, 2000 and 2007. So, in the long arc of market history, stock prices weren't exactly attractive and were ripe for a correction.

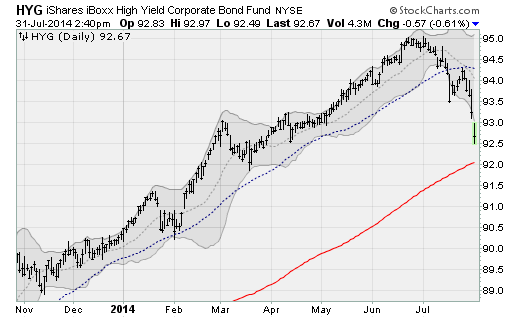

The bond market is also getting hit very hard -- likely in anticipation of a change in Federal Reserve policy -- on a scale that hasn't been seen since last summer, as the chart above shows.

The fundamentals also suggest some additional downside risk here. With the economy strengthening, and the unemployment rate falling very near the Congressional Budget Office's estimate of full employment (with the wage gains and inflationary pressures that should follow), the Federal Reserve could very well tighten policy sooner than expected.

That's especially true after Philadelphia Federal Reserve President Charles Plosser dissented and voted against Wednesday's Fed policy statement because of his objection to his colleagues' commitment to hold interest rates near zero "for a considerable time" after the QE3 bond-buying stimulus ends.

The policy hawks are quickly making their reservations known, with Plosser's vote coming on the heels of Dallas Fed President Richard Fisher's Wall Street Journal Op-Ed on Tuesday titled "The danger of too loose, too long."

This is a big deal because it has been eight years since the Fed last raised the cost of money. And a change could happen as soon as early next year, if inflation, housing and the job market rise faster than the Fed expects.

Plenty of other dangers are lurking. Conflicts in Ukraine, Iraq, Libya, Syria and Israel all have the potential to worsen considerably. And the worst-ever Ebola outbreak is underway in West Africa. An epic drought is still scorching the fertile farmlands of California. And the sure-to-be-contentious midterm elections are just a few months away.

Investors clearly have a lot to worry about. And after ignoring all these negative catalysts for months, they're suddenly feeling weak in the knees as reality rushes back in. It's likely to get worse before it gets better.