Why the House could be (but really isn't) in play for 2014

After polling showed Republicans took the bigger political hit from the 16-day government shutdown, House Speaker John Boehner, R-Ohio, was asked what it could means for his House majority. He said Republicans will be fine - and he's likely right. The Republicans do remain favorites to hold the House, underpinned by still-strong support from conservatives in a lot of safe districts. But that's not the whole story.

"Fine" doesn't sound as buoyant as, well, "well" or "good" which - intentional or not - feels like an apt word choice. Yes, the Democrats got the better of the shutdown fight, but the best word for the whole political environment may be "uncertainty," given the public's anger. If nothing else, 2014 just got a lot more interesting. Here's what we see (and why so much is unsettled) in the House landscape one year out.

The big picture: It looks like anti-incumbent fever is building - though that doesn't mean the House flips.

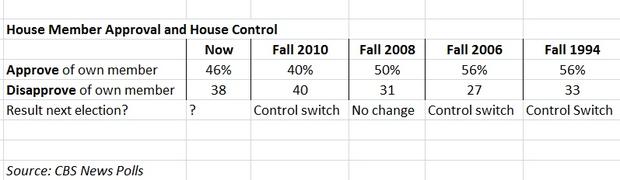

The latest CBS News poll showed just 46 percent approve of how their own representative is doing, which drew attention because the number is "underwater," or less than half. Historically, though, that does not mean the House will flip. Consider:

That measure hit its lowest-ever number in 2010 (at 40 percent) and that year Republicans did retake the House, in an historic wave. But it was also underwater in the fall of 2008, and Democrats went on to keep House control. Before House control flipped in 2006, it also proved a lousy predictor because a majority 58 percent approved of their own member. And in October of 1994, before House control flipped, 56 percent approved of their own member.

Years ago this "own member" approval number was routinely in the low-60s or mid-50s nationally, whenever the CBS News poll asked it, going back (albeit, intermittently) all the way to the 1970s, which is partly why people still use the line "Americans hate Congress but love their own congressman." Back then ticket-splitting was more prevalent and people really did like their own congressman more. But that hasn't been the case for years now. Today partisanship drives these views more than locality.

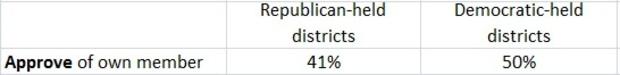

Voter anger and the uncertainty that comes with it cuts both ways, and Democrats have a lot of seats in marginal districts of their own to defend in 2014, which is another reason this measure (like the generic ballot) has issues as a predictor. If there is an edge for Democrats in these numbers, it's that Republicans have slightly lower own-member approval in districts they hold than the Democrats do in theirs. Democratic members get 50% from voters across their districts, Republicans 42 percent in theirs.

The districts: Some in play, many to watch; lots of fights for Democrats too

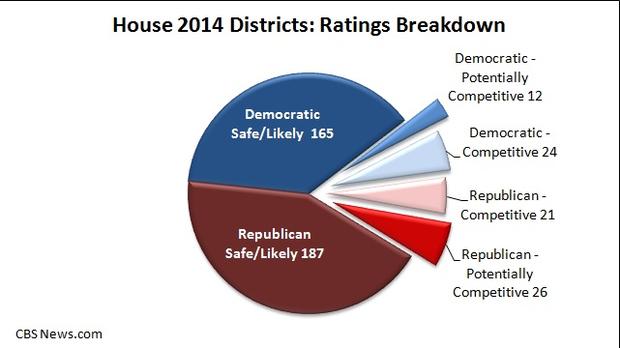

The biggest issue for competitiveness and for hopeful Democrats is that this is not a one-way street. They have a lot of marginal districts of their own to defend too. Many of them are in territory that gets harder in midterms because the electorate tends to get a little older and less liberal.

Depending on the outcome of some special elections or other factors, in 2014 control could take a net gain of 16 or 17 seats. That seems like a few, but most districts aren't competitive.

Here's one item in Democrats' favor: The average partisan index of Democrats' potentially competitive seats is +5 Democrat, which means Republicans have to do some real work to move them into contention. If the GOP's standing with moderates isn't good, it's harder to see how that happens. The average index in Republicans' potentially competitive districts is +2 Republican, so some of these could move into range if the Democrats catch any kind of momentum.

The party image battle: Democrats are winning, but it's all relative

When we look at the impact of the shutdown and incumbents across Democratic- and Republican-held districts, we see much the same effects we do nationally: Democratic incumbents came out of this a little more insulated from anger than their Republican counterparts. Voters who live in Democratic-held districts give their own Representative slightly higher average approval ratings (50 percent) than voters represented by Republicans (41 percent.)

The Democrats' congressional delegation, as a whole, finds better favor in Democratic-held districts (38 percent) than the Republican delegation gets across Republican-held districts (20 percent). Neither is great; neither is above 50 percent, but it looks like a relative edge at this point. (One caveat is that some of this is to be expected, as Republican-held districts aren't quite as lopsidedly partisan to begin with as are Democratic ones.)

Perhaps the single biggest issue for Republicans, if there is one, is that moderate voters consistently blamed them more for the shutdown. Republicans will do just fine by hanging on to conservatives and reliable partisans in a lot of their safe districts, but if we see consistent movement away from moderates (over time; we're not there yet) it could lead to tougher fights in districts on the margins. It is historically hard to flip a CD even a few points in the direction opposite its usual voting pattern, but if some are starting to move, the moderates are often the first warning sign.

Even if it's too soon to say that the shutdown made more seats competitive, but right now we're looking at indirect effects: its impact on the parties' overall images could draw money and candidates off the sidelines. The environment could persuade more Democratic candidates to enter marginal district races, and want to campaign under the party banner, which could in turn put more districts into play.

The Budget Vote: Maybe a big deal, maybe not

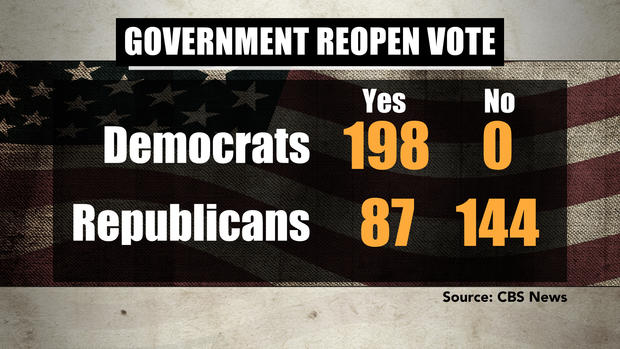

Americans told us they'll weigh their member's debt ceiling vote when it comes time to evaluate them. Given the negativity and anger directed toward Congress during the shutdown, that doesn't sound like good news for anyone. But members votes on the final budget deal ultimately synced up with what voters in the districts wanted, so there may be a limit to the damage.

House Republicans who voted "no" on the debt ceiling and budget deal came from much more conservative districts, as we noted last week, and in this poll we find that their voters disliked the deal, too - at a rate of 56 percent in districts whose members voted "no." So these members and voters were mostly in step. And a lot of Republicans in more marginal districts also voted "yes," which could insulate them (though less so if a primary challenge comes along.)

People whose representatives said "yes" to re-opening the government and raising the debt ceiling tended to favor that agreement 51 percent to 41 percent in the poll, so those members were mostly in line with their districts too. All of which means: some members will surely be on the wrong side of this issue for their districts, and campaigns against them will certainly bring that up, but many were in sync, and so that'll have to play out on a case by case basis. Moreover, we have to leave with this thought: coming out of the shutdown the big news has been the problems with the Affordable Care Act website. Democrats were defending the new program in the shutdown - the next item to watch is whether its rocky rollout cut against those Democrats after all, or take some of the luster off their recent (and relative, and maybe fleeting) political win.

All of which adds to an uncertain environment. On balance, that may be a net positive thing for Democrats, who would probably take their chances (however slim) with uncertainty, considering where things stood before the shutdown. It's at least looking like a more intriguing year than we'd expected -- even if Democrats shouldn't be getting too excited just yet.