Why THAAD is controversial in South Korea, China and Russia

The U.S. military now has an advanced Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) anti-missile system up and running (mostly) in South Korea, ready to take out at least some missiles that Kim Jong Un's rogue North Korean regime could launch.

The objective of the THAAD deployment, which the U.S. agreed to pay for under an agreement between the Obama administration and South Korea, is to protect U.S. troops in Asia and allies like South Korea and Japan from a potential North Korean attack. But opposition to it has been fierce, and it has already had very real implications. Here's why:

China's objection

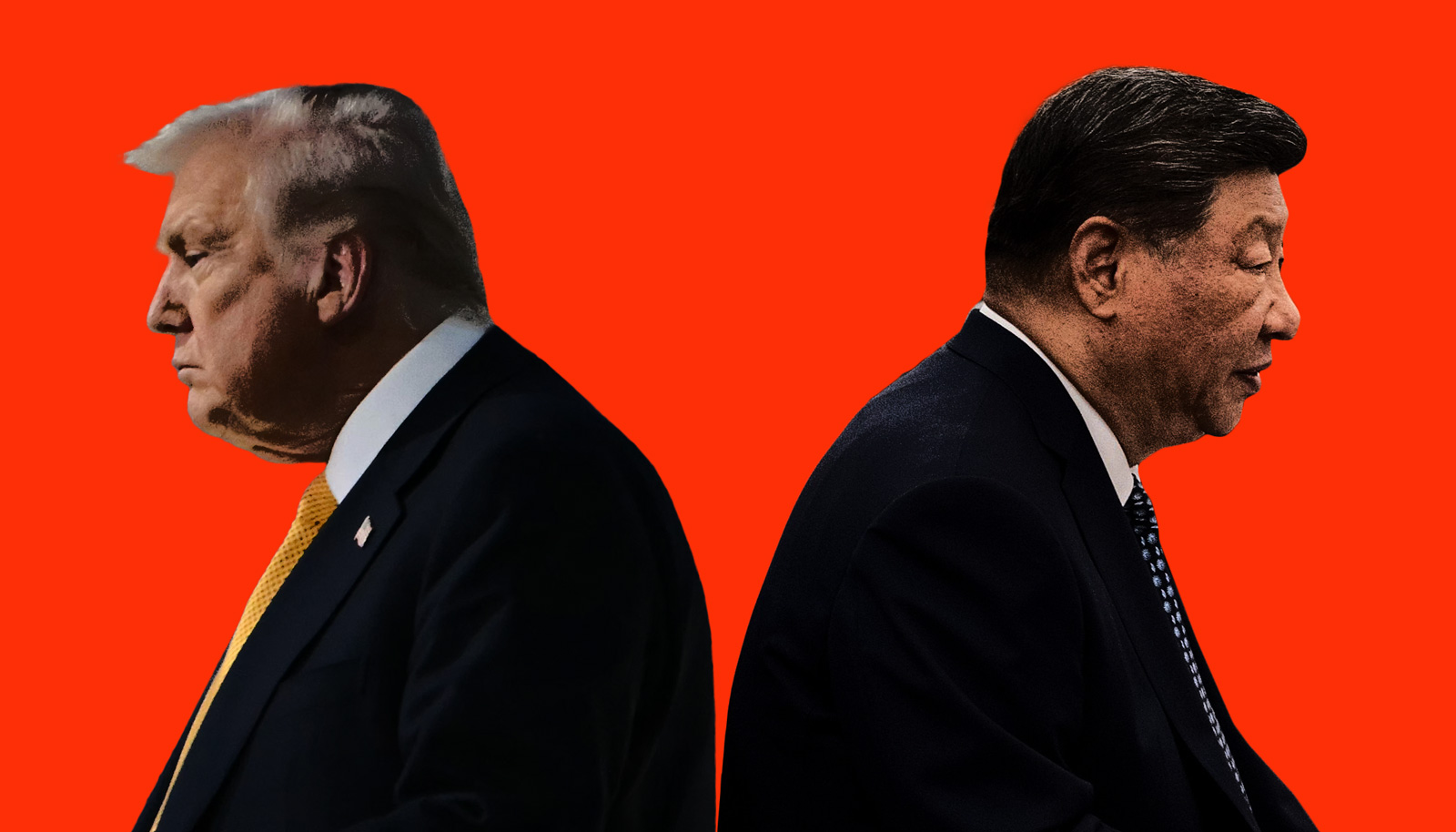

China is furious about the THAAD deployment, and that complicates the already-daunting challenge President Trump faces in trying to resolve the standoff with North Korea.

While Beijing has almost certainly grown weary of Kim Jong Un's repeated refusals to play by the rules of international conduct and stop testing nuclear devices and missiles, China remains, at least for the purposes of broad definition, an ally of North Korea and a strategic competitor of the United States.

It is not the prospect of the U.S. shooting down a North Korean missile irking Beijing, but rather the ability. THAAD's advanced radar system gives the U.S. military the ability to peer across the Yellow Sea into China's own airspace and potentially to track the movement of Chinese military hardware on the ground.

Beijing has voiced its strong disapproval since the THAAD deployment in South Korea was first announced. That annoyance was reiterated Tuesday by Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Geng Shuang, who urged "relevant sides to immediately stop the deployment."

He added, without any clarification, that China would "firmly take necessary measures to uphold our interests."

China's disapproval is perhaps the most problematic, given the Asian behemoth's unique role as longtime benefactor of the North Korean Kim dynasty. Beijing remains far and away the most valuable trading partner -- virtually an economic lifeline -- for North Korea.

President Trump and his top aides have made it clear that they want China to try to force Kim back to the negotiating table by curtailing that trade.

China doesn't want a war on its border for a number of reasons, and there have been real signs that it's tightening the financial screws on its old ally North Korea. But THAAD remains a massive hurdle in the dialogue between Beijing and Washington.

South Korea's objection

Even South Korea, the primary country that THAAD seeks to defend from the aggressive and unpredictable neighbor to the north, is far from unified in its stance on the anti-missile system.

Opposition, which has manifested itself in large demonstrations across the country, is multi-faceted, but stems primarily from concerns that the protection THAAD offers may not be worth the massive hit to relations with neighbors China and Russia, which also opposes the deployment.

THAAD is designed to target and intercept short and medium-range missiles fired by North Korea. It is not an effective countermeasure against intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM), and with a range of only about 125 miles, it may not even be able to protect all of South Korea.

South Korea knows that the best way to prepare for an attack by North Korea is to avoid one, which makes diplomatic relations with the North's ally China critical. China has not hesitated to make its displeasure known in South Korea.

For months, South Korean businesses have suffered loosely veiled, unofficial economic retaliation from China, and threats of much harsher measures should the full THAAD deployment be realized.

There are also health concerns among South Koreans who live near the THAAD installations and fear the powerful radar systems could emit damaging radiation.

Russia's objection

Like China -- and recently, to an even greater degree -- Russia has shielded North Korea from harsher sanctions by wielding its veto power on the United Nations Security Council.

"Relevant countries shouldn't use Pyongyang's acts as a pretext to increase their military presence on the Korean Peninsula," Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said in April 2016.

Russia's objection, like China's, is rooted in the country's role as a geopolitical adversary to the U.S. -- Moscow is just as reluctant as Beijing to have a powerful U.S. military radar system sitting just hundreds of miles from its territory.

Russia and China are also allies, and the Kremlin has repeatedly voiced its concern that the THAAD deployment could further "destabilize" the region.

Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Gennady Gatilov said at the end of last month that the anti-missile system posed a threat to "the existing military balance in the region."

"It is not only we who perceived this step very negatively. We are once again urging both the United States and the Republic of Korea (South Korea) to reconsider its expediency and other regional states not to yield to the temptation of joining such destabilizing efforts," Gatilov was quoted as saying by Russian media.

In short, the controversy over the U.S. THAAD deployment in South Korea boils down to whether the system's limited capability to defend Americans and American allies is worth the potential impact to the political process aimed at ensuring it is never needed.