Why is this market so crazy?

For casual investors, it must seem like the financial markets have overdosed on crazy pills.

We've got a red-hot IPO in Friday's Alibaba (BABA) launch, bringing back memories of the dot-com bubble's heights. We've got the Dow Jones industrial average and the S&P 500 pushing to new highs, while the small-cap stocks in the Russell 2000 are on track for the first "death cross" since 2011. The Dow has been up five days in a row, but the Russell 2000 has dropped back below its 200-day moving average.

And while large-cap stocks are flying higher on the expectation the Federal Reserve is going to hold off on short-term interest rate hikes for as long as possible, other areas of the market -- like currencies and precious metals -- are preparing for the first increase in the cost of money since 2006.

Things are sort of all over the place.

Just look at the reaction to Thursday night's Scottish independence vote. The British pound soared against the Japanese yen as traders realized the union would be preserved.

The yen has been hit by terrible economic data and the realization that Japan's goose is probably cooked in terms of too much debt, not enough growth and a paucity of new ideas to get it out of its funk. The latest obsession is the idea that Tokyo will plunge more money into the stock market by raiding state pension funds, moving money out of the safety of bonds.

And yet, Japan's Nikkei stock index jumped 1.6 percent to close at a seven-year high.

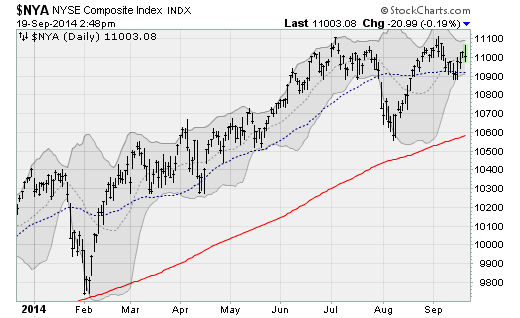

The truest sense of where things stand is probably provided by the more somber NYSE Composite Index, which as shown above, has been sliding sideways since June after recovering from the steep drop in August.

But behind the façade of price stability, market internals suggest the situation is weaker than it looks: Less than 50% of the stocks in the NYSE are above their 50-day moving average, a measure of medium-term trend. That's down from 65% at the start of September and nearly 85% back in July.

All of this confusion is coming at a time of high investor confidence that borders on complacency as well as full stocks valuations. Rarely has the market, based on price-to-earnings measures, been higher. And when it has, it was in 1929, 2000 and 2007.

So what are investors to do?

With the risk-reward ratio skewing toward unfavorable as we head into the end of the Fed's QE3 bond-buying stimulus in October, the sure-to-be-contentious midterm elections in November and the eventual start of the Fed's rate-hiking campaign in the middle of 2015, I continue to recommend investors remain cautious.

That means raising cash where possible, avoiding the urge to chase the market higher and thinking about protection instead of profits as big market catalysts approach.