Why immigration reform faces an uphill battle in the House

We haven't seen any polling on this, but we'd wager that few Americans outside D.C. know what the "Hastert Rule" is. And who could blame them? It isn't even a written rule. But it does help highlight the pressures in the Republican conference right now as it wrangles with immigration reform, and the way Congress operates in this new era.

When they assembled this week to map out their approach, House Republicans made clear they won't be taking up the Senate's "gang of eight" bill because not all House GOP members support it. Many expressed principled disagreement with the policy; still others said they were skeptical that the Senate bill's plan for border enforcement - which they prioritize - would really happen.

- Dim prospects for comprehensive immigration bill in House

- McCain, Schumer put positive spin on House immigration plans

Many national Republicans see an immigration measure as a step toward making inroads with Hispanic voters, who have growing clout and have voted overwhelmingly Democratic. But House members' political calculus can be - by design - very different from the Senate's, and probably from those looking to steer the national party's "brand." The thought of primaries or voter anger back home might outweigh the allure of any gains for the national party from appealing to Hispanic voters (or, at least, by not continuing to do things unappealing to Hispanic voters).

On "Face the Nation" two weeks ago, host Bob Schieffer pointed out the conservative and non-minority composition of many GOP districts, adding he's "noticed over the years that when politicians of either party are given the choice between personal survival and party survival, they usually choose personal."

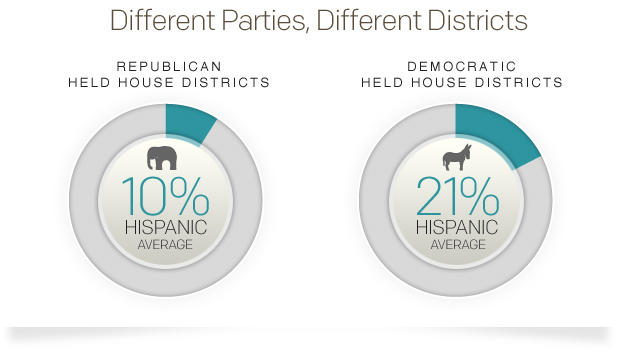

Republicans' districts average just 10 percent Hispanic voting age population. (By contrast, Democrats' districts average more than twice that, on average.) There simply aren't many Hispanic voters for many of these members to appeal to.

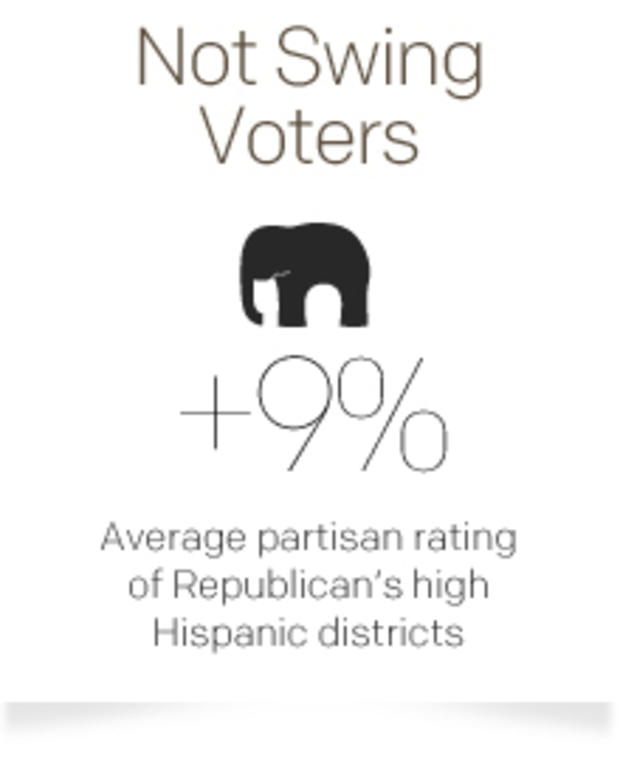

Here's the kicker: even the handful of GOP districts that do have a sizeable Hispanic share (greater than 20 percent) are not even swing districts. They have a CBS average partisan rating of +9 so Republicans don't usually need the Hispanic voters in them, anyway.

All told, this is only 14 percent of their conference, or 32 seats. There are some - particularly in Texas, California, and perhaps Florida - where a GOP House member might breathe a little easier if they got more of the Hispanic vote, but those are not numerous enough that those members can force the conference.

No one is saying the House can't pass immigration reform. The question is: Can it pass something with a path to citizenship for those immigrants in the country illegally, which is a requirement of the Senate Democrats and the president?

Some members might fear conservative primary challenges in their district should they go the wrong way on this, coming from partisans who'd balk at anything that looks like amnesty. So policy concerns aside, they face the question of a vote for a hypothetical, unproven potential help to the party's future in upcoming Presidential or Senatorial elections or risk their own political future in their own district. The peril in their own district may be more tangible, or at least more imminent.

Business interests in favor of reform might pressure the House. They might be pitted against outside conservative groups opposed to it who readily boast of multimillion dollar campaign spending against Republicans who don't stay in their good graces. Today's PACs can and do reach into any district in the country to target members, often taking sides in primaries or runoffs between candidates of the same party, for the candidate who best fits the policy goals. We've seen outside groups repeatedly back one Republican candidate over another in the last few cycles, and this is the kind of issue that could open the door to those scenes again. Many of the House Republican seats are safely Republican (the average GOP member won with about two-thirds of the vote) but that just means more conservative voters to rally against them in a primary, more so than in moderate districts.

There's yet another way this is particular to the House and districts: Republican voters nationwide have generally shown some support for a combination of bolstered border-security and conditional path to citizenship. An April CBS News poll didn't find much difference between Republicans, Democrats and independents on the matter. Moreover, to the extent this is supposedly about conservative voters who'd be upset, it didn't find a significant difference between conservative Republicans and the rest of the party, though sample sizes somewhat limit the ability to test this fully, and the political reality is that it doesn't take a majority of Republicans to generate a primary challenge, only a handful of committed ones. And outside money can help turn a small movement into a force.

This is all another example of how parties are increasingly nationalized, too, and it's especially interesting against the backdrop of immigration policy. Immigration issues have often crossed party lines and split members as much by region, or by ties to particular businesses, at least as much as by party. They just did again: in the Senate, Republican senators from border and high-immigration states were in favor, like Sens. John McCain, R-Ariz., and Marco Rubio, R-Fla.; and opposed, like Sens. Ted Cruz and John Cornyn from Texas.

House Speaker John Boehner, R-Ohio, said "it's always in the party's best interest when we're doing the right thing for the country." But not everyone defines what's best for the party - or for that matter the country - the same way. And the House of Representatives doesn't naturally foster broad governing coalitions of supporters across the electorate. Redistricting has made it likely the GOP can keep control of the House for a while, but it also means more conservative districts electing more conservative members.

There's a twist here, too, on the classic tension of district representation versus the national party, in that many Republicans in the House, especially those elected through the help of tea party groups, aren't strongly aligned with the dictates, such as they are, of the national party on this or many issues. Rather they see themselves as part of a national movement that is rejecting what they see as the status-quo national party and its apparatus. That, in turn, has put extra pressure on Boehner to try to hold together the conference.

And hence, the "Hastert rule:" a bill or a series of bills, as may be the case here, won't come to the floor until most Republicans are behind it, so the House GOP will speak with one voice on this, despite its divisions. Or as Rep. Tom Cotton, R-Okla., stated in a Wall Street Journal editorial, there will be a House Republican bill, or no bill at all.

Whether or not that would pass the whole chamber is another matter. Getting a House bill becomes a harder climb because it won't simply be a matter of finding a majority of House members in support (some combination of Republicans and Democrats) it'll be a matter of finding something a majority of Republicans will support. And their pressures, in this era of nationalized parties, outside money, and local voters, are simply different mix than many others.