Why humans are wild about apes and monkeys

LOS ANGELES - Movies have been messing with apes since a Hollywood director captured and chained that great gorilla on Skull Island and brought him to Broadway in 1933's "King Kong."

The reason, of course, is as plain as the image in the mirror. Apes and monkeys: They're like us, but they're not us. That's the fascination. And it's a great starting point for all kinds of storytelling, be it comic or cautionary.

This summer, movies have served up quite a bit of both, offering a barrel full of monkeys that, at the risk of offending Bonzo and Mighty Joe Young, eclipses all previous comers, not to mention the rumbling robots, pirates and wizards currently littering the multiplex.

Monkeys and apes are everywhere, from Crystal, the crazy capuchin seen in "The Hangover II" to the bromance between Kevin James and the Nick Nolte-voiced silverback gorilla in "Zookeeper."

"Dirty Hairy": Can chimps really shoot guns?

Freida Pinto, "Rise of the Planet of the Apes" cast, step out

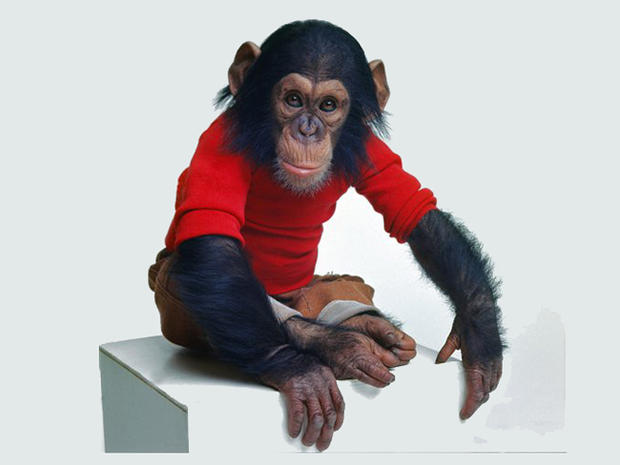

Then there's this story of human hubris: Scientists perform experiments on a young chimp and, afterward, abandon it, leaving the animal caught halfway between man and monkey.

It's the premise of not one, but two summer movies: the upcoming reboot "Rise of the Planet of the Apes" and the Sundance Film Festival documentary sensation, "Project Nim," which chronicles a Columbia University professor's radical attempt in the 1970s to teach a chimpanzee sign language by raising it as a human child.

"They're science-fiction and we're science-fact," says "Project Nim" producer Simon Chinn, whose film is currently expanding its North American run.

"The fascination in our movie comes from watching the similarities between chimps and humans, yes," Chinn adds. "But if there's any lesson to take from the film, it's that, while there may be a lot of overlap, chimps are very distinct and should be left to live among their own kind."

Or risk, in the case of "Rise of the Planet of the Apes," a primate rebellion that its makers liken to the classic Roman slave revolt epic "Spartacus."

What separates this "Apes" movie from the 1968 Charlton Heston sci-fi adventure, its sequels and the 2001 Tim Burton remake is both its present-day earth setting and its point of view.

"The ape is the star of the film," says 20th Century Fox chairman Tom Rothman. "The movie starts out relatively conventionally, but, after something unfortunate happens and the ape is put in a `sanctuary,' which to the ape is just jail, the movie stays with the ape. The rest of the movie is his story, told from his perspective."

"The key," adds "Apes" director Rupert Wyatt, "is in the telling for you to understand whose side we're on. And it's not the Romans." Maybe that's OK. Humans have a "deep, intrinsic attraction to primates," says San Diego Zoo animal care manager Greg Vicino, that goes beyond the mutual owning of opposable thumbs. Like people, monkeys and apes (how to tell the difference: most monkeys have tails) maintain intense relationships through sophisticated social behavior.

"They follow physical signals, gestures, postures and vocal behavior in order to dictate how they behave," Vicino says. "They're fascinating because they appear so human in so many ways. Yet, it's also the subtle differences we find irresistible. You can't predict what they're going to do."

Those mercurial mood swings entice screenwriters to create wild scenarios for their monkey characters. Take the super-smart capuchin Crystal: She plays a cigarette-smoking drug dealer in "The Hangover II" and then, voiced by Adam Sandler in "Zookeeper," dishes out relationship advice to Kevin James. ("Throw poop at her!")

Over the past eight years, several capuchins have played Jack the Monkey, a screeching mischief maker seen in all the "Pirates of the Caribbean" movies, including this year's "On Stranger Tides."

"Monkeys are childlike and can act on just about every impulse and nobody judges them for that," "Zookeeper" director Frank Coraci says. "Add in that they're 20 times stronger than us, and they're living the dream life for a lot of dudes."

Should filmmakers decide to pursue a more serious route, apes and monkeys can hold up a mirror so humans can examine their own behavior. As we watch the chimp in "Project Nim" being shuttled between various homes and facilities, it's easy to view the film as an allegory for parenting.

Says producer Chinn: "I first saw it as a story about how we as adults in society sometimes discharge our responsibilities to those who are more vulnerable, be they chimps or children."

Not that the message always needs to be profound.

"Sometimes you just want to monkey around with your persona, with your image," Clint Eastwood tells The Associated Press, talking about his surprising, mid-career comedic turns opposite an orangutan named Clyde in 1978's "Every Which Way But Loose" and its sequel, "Any Which Way You Can." "Or maybe I just got tired of riding a horse and needed something new."