"Euro-QE" isn't exactly an all-clear for investors

For even the most casual market observer, the meme underlying this bull market is pretty clear: Whenever anything bad happens, or even threatens to happen, the major central banks will rush in and print more cheap money.

Stocks haven't suffered so much as the indignity of a typical 10 percent price correction since early 2012. After that, the Federal Reserve unleashed its "QE3" program, the Bank of Japan went all in on "Abenomics" and crushed the yen, and the European Central Bank (ECB) hinted that it would buy eurozone government bonds in volume -- overriding German political concerns and legal hurdles -- to protect the currency union.

Since then, the S&P 500 has surged a whopping 63 percent. With interest rates at 14th century lows across Europe and trillions in high-powered money coursing through the veins of the global financial system, why not join in? For years, you couldn't lose.

The ECB delivered the latest injection of monetary meth on Thursday, finally unveiling the "Euro-QE" program it had been hinting it. The details were largely as expected, though a bit on the high side, with monthly purchases of 60 billion euros through September 2016, with room for more if inflation and growth don't improve by then.

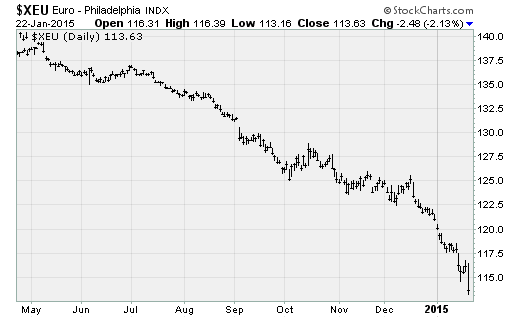

In response, the euro dropped hard (chart below), which appears to be the primary policy goal in an effort to boost export competitiveness.

Stocks soared in response, with the major U.S. indexes wiping away their year-to-date losses. It's tempting to assume that the song and dance will continue. But here are some wrinkles that threaten the narrative.

For one, unlike in 2012, central banks are no longer united. Some are breaking rank, violating the script and increasing volatility as a result.

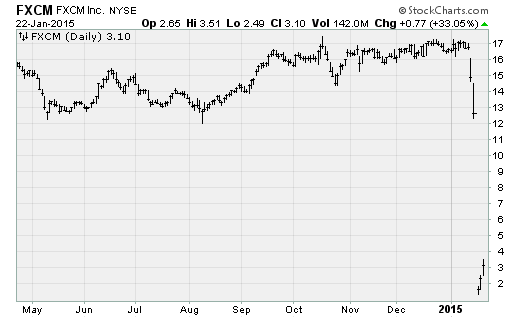

Last week's surprise move by the Swiss National Bank to end the Swiss franc's peg to the euro -- resulting in a sudden 30 percent appreciation -- caught many macro hedge funds and currency brokerages wrong-footed, as the chart of FXCM (FXCM) shown above attests. Denmark recently cut rates as well for the same reason: exposure to the collapse in the euro.

Next week, the Federal Reserve will likely reinforce the message that it's preparing for its first rate hike later this year since 2006. Recent strength in the dollar has forced panicked rate hikes by Russia and Brazil. Commodity market weakness encouraged the Bank of Canada to cut rates on Wednesday.

The problem is that unlike in 2012, the situation has evolved. Doubts are growing about the efficacy of cheap money pumping, as Japan's ongoing malaise suggests. Economic weakness across Asia and Europe, juxtaposed with America's strong job market and consistent GDP growth, has ignited the dollar higher. But that has also helped crush crude oil by nearly 57 percent from last summer's highs.

The drop in energy prices, along with the specter of wage inflation in the U.S., currency movements and a slowdown in foreign economies, creates a situation that feels similar to what happened in the late 1990s. We had the Asian financial crisis (triggered by currency volatility), the Russian bond default (precipitated by a large drop in crude oil prices) and a "profit recession" here at home. The S&P 500 dropped 20 percent in the midst of strong job creation and steady GDP growth.

Europe's new stimulus program will, if anything, magnify these dynamics. That's because concern is real and growing that Euro QE won't fix the structural problems at the eurozone's core.

According to the economists at Societe Generale, because of these problems the ECB's program needs to be triple the announced size to work -- something on the order of 3 trillion euros in total purchases.

In the estimation of SocGen's Michel Martinez, Euro-QE "could be five times less efficient than in the U.S." The team at Capital Economics warns that while the ECB's announcement didn't disappoint, the mixed global record of quantitative easing suggests it "won't miraculously cure all of the currency union's problems."

We'll know for sure later this year, as the economic data either prove or disprove these worries. Sunday's Greek election results could also upend the situation.

For now, investors should avoid the temptation to believe this is 2012 all over again.