Why don't Americans trust government?

Trust (noun) 1: assured reliance on the character, ability, strength, or truth of someone or something. (Merriam-Webster)

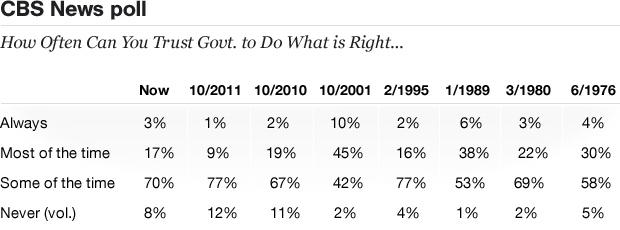

Skepticism about government is, in many respects, part of our national DNA. But surveys in the 1950s and 1960s showed most Americans expressed at least a basic trust that their government would do the right thing most or all the time. The 1970s and the tumultuous issues of Vietnam and Watergate eroded that sentiment, and the polling numbers on it have never really recovered.

- Poll: Obama's approval stands at 52 percent

- Poll: On deficit, immigration, guns, public in sync with Obama

- Complete coverage: CBS News polls

Our own trend picks it up in 1976, when just a third said the government did right most or all the time; by 1980 that had dropped to a quarter. Things rose a bit in the late 1980s, dropped again in the 1990s, spiked up amid a welling of patriotism in the fall of 2001, and bottomed out - our lowest number ever - last year, after the 2011 budget showdown and America's credit downgrade.

Today trust in government, as measured by ourlatest CBS News poll, has inched back up to a still-low (but about normal for the era) 20 percent, with Americans trusting government just "some of the time" the most prevalent answer.

This week, as another legislative session really gets rolling, we decided to ask the 78 percent of Americans who don't trust it most of the time to tell us why they don't, and we asked these skeptical Americans to describe their beliefs in their own words. The replies we got described a frustration with ineffectiveness and partisanship; misgivings about an insular Washington wrapped up more in its own battles than in working for average people. To many, it seemed, lack of trust was born not from apprehension about what a government might do to you, but rather that it isn't doing anything for you.

"They can't make a mutually agreeable decision together," said one interviewee, "They cannot be trusted to work together," said another, riffing on the question's phrasing. "The fact that they fight all the time."

Views of Washington being removed from 'the people' were exemplified by thoughts like "they (politicians) ...are set for...years, so they don't think about us anymore;" they "can't relate" and "don't know what's going on with the common man." "What's good for the country isn't good for Congress."

These kinds of quotes, along with general complaints about perceived pandering and influence of lobbyists or special interests, were more prevalent than comments about any specific policy and comprised about one in five answers (22 percent, a plurality.) Another quarter decried either what they saw as untrue statements from politicians (15 percent) or the prevalence of money in politics (11 percent).

Given the tough, often personal rhetoric that surrounds politics and elected officials today, it might surprise - perhaps, happily - that the answers didn't get more personal. Few volunteered an elected official's name, nor a party nor a prominent leader past or present - as an ad hominem reason for their distrust. Rather, answers tended strongly toward the institutional and structural, as exemplified by those mentions of interests and infighting. Maybe part of that is due to the phrasing of question (we asked "what" you distrust, not "who") but it also suggests that this cynicism transcends any current occupant of an office or seat, too. Like the trend line that led here from the 1970s, it is deeper and more prevailing.

And so it's a reminder, too, that regaining trust - if it happens - isn't likely to come via a single election or figure or policy but, as it would always be between people, something that has to build over repeated actions and time.

Within the overall numbers there is some partisanship, which isn't unexpected.

Though Democrats are - importantly - still mistrustful, overall they're more likely to be trusting that Republicans are. (35 percent of Democrats trust the government today - still less than half - while only 9 percent of Republicans do.) This kind of pattern has been the case over time for partisans who don't hold the White House.

During President George W. Bush's term Democrats tended to answer the question more negatively than Republicans. For example in 2005, when 32 percent of Americans expressed trust all or most of the time, 52 percent of Republicans did, and 19 percent of Democrats did.

There have been similar findings elsewhere. The Pew Center, which also regularly tracks trust and has for years, did a nice graph of the timeline and split between Republicans and Democrats here. And some of this, too, is probably the inevitable disappointment that comes in a democracy where few, if anyone, get everything they want, even when they hold the presidency. In our responses this week Democrats were a more likely (23 percent) than Republicans (12 percent) to blame ineffectiveness for their lack of trust.

But just as the responses to the volunteered answers in our poll weren't pointed at a single party, neither should the partisan splits overshadow the larger point because trust has declined over time for partisans of all stripes and the difference only tends to be relative.

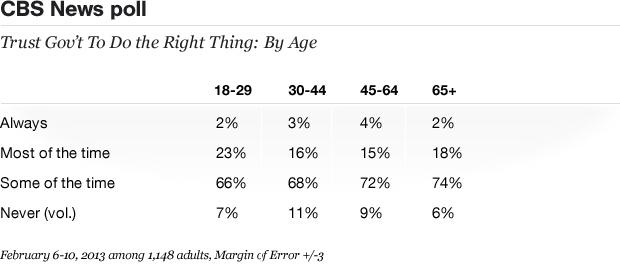

Nor is there substantial difference today on age. Some might speculate that mistrust could build over time or that it might be stronger among people who lived through more events that inspired it. But that's not the case in our latest measurement. Young people today trust the government to do what's right only marginally more than older folks.

Some of this sentiment, of course, probably emerges from conflicting views on what, exactly, is "the right thing" for government to do. But it also speaks to just how widespread the view has become - perhaps one of the few things on which folks from all sides of the spectrum agree.

Follow on twitter @salvantocbs