Why al Qaeda's still a threat in Afghanistan

This story was filed by CBS News terrorism consultant Jere Van Dyk, author of "Captive," Times Books, 2010.

On Sept. 20, 2001, President George W. Bush told Congress, "Our war on terror begins with al Qaeda, but... It will not end until every terrorist group of global reach has been found, stopped and defeated."

On Aug. 19, 2011, Marc Grossman, President Obama's special envoy to Afghanistan and Pakistan, told Radio Free Europe, "The job President Obama has given us is to deter, deny, and defeat al Qaeda in Afghanistan. I think we're well on the way to doing that."

Ten years after the Sept. 11 attacks on New York and Washington, does al Qaeda in Afghanistan or Pakistan still pose a threat to the U.S.?

9/11: Ten years laterIn October 1981, I went as a young journalist to Peshawar, Pakistan, to meet the leaders of the Mujahideen - America's allies in the war against the Soviet Union - and to live with their men in Afghanistan.

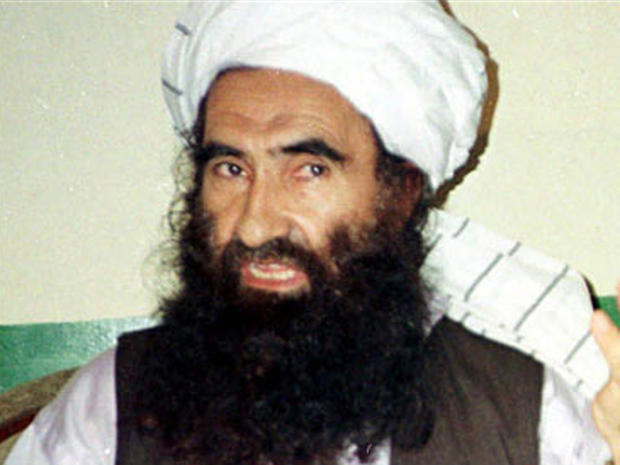

I met Gulbadeen Hekmatyier, Yunus Khalis, and other leaders. I liked Khalis and went with his men into the tribal areas and hiked up the mountains into Afghanistan to the bombed, baked-mud compound of Jalaluddin Haqqani, a Mujahideen commander.

It was at a place called Shi-e-Khot. Haqqani gave me a plate of honey to go with my tea.

An Egyptian Army major came to stay with us. He hated me because I was American. He was arrogant and the Afghans didn't like him, but he seemed to have power over Haqqani, and they deferred to him. Haqqani allowed him to fire a surface to air missile. He missed his target, a Soviet helicopter, and the Afghans laughed behind his back. I realized years later that the Egyptian major was the beginning of al Qaeda's influence in Afghanistan.

According to the 9/11 Commission, from 1996 until Sept. 11, 2001, between 10,000 and 20,000 foreign fighters came to Afghanistan and trained in camps run by al Qaeda. Al Qaeda's camps were mostly in Haqqani territory.

Today, Haqqani is the patriarch of the Haqqani Network, the most lethal insurgent group in Afghanistan. He was once a lowly mullah who ministered in a small baked-mud mosque outside of Khost. Today, his giant white marble mosque with turquoise minarets looms over Khost like a cathedral over a village in France or Spain.

In 1984, the Mujahideen, under Pakistani tutelage, formed the Afghan Mujahideen government-in-exile in Peshawar. A few months later, Pakistan and the U.S. brought the government to the U.S. to present its credentials to the U.N. and to meet with President Reagan. I sat in a hotel room in New York with Hekmatyier, president of the government.

A call came from the State Department. "Tell Mr. Hekmatyier it's confirmed that he and other members of his government will meet with President Reagan in the Oval Office," said the caller. He gave a date and time. I told Hekmatyier.

"I can't do that," he said softly. I told the State Department official. He screamed at me on the phone. "Who does he think he is?"

He knew who he was, an ambitious, ruthless man whose Mujahideen fired on other Mujahideen as well as the Russians. He was a guest in the U.S. and had the gall, and, I noted, the courage, to say no to the most powerful man in the world, who was providing millions of dollars in arms and ammunition, sent through Pakistan's ISI military intelligence agency, to him.

In 2007, he told Pakistan's Geo television that his men helped bin Laden escape from Tora Bora, but said he had no links to al Qaeda today. He is based in Chitral, Pakistan, and is still fighting the infidel, foreign invaders, 35 years later.

In December 2006, I disguised myself as a Pashtun and went up into the mountains of Khost Province, along the Afghan-Pakistani border. I realized I had been here before, with Haqqani's men. Nothing had changed, except now I was the enemy.

My guide pointed east, toward Pakistan. "Jalaluddin is over there," he said softly. "The Taliban come across through that valley."

I wanted to see Haqqani again, and find out about al Qaeda. I spent months traveling, off and on, along both sides of the border. Tribal leaders blamed bin Laden for "burning their houses" - the destruction of Afghanistan. Others said he was a good Muslim. No one said he could hide him for longer than a day or two. He was too big, too important.

In November 2007, I sat in a mountain village across from a Taliban commander. Why was he fighting?

"We are fighting jihad," he said. Who supported him? "Pakistan," he replied. "We live in the mountains, but for training we go to Pakistan. Sometimes the army comes and trains us."

A few of his men stood in the doorway, among them a thin young man wearing a red and white kefeyyah, like men wore in the Middle East. He was al Qaeda. I asked who was in charge, the Taliban or al Qaeda.

"We are," said the commander. "Al Qaeda is also fighting for Islam, and they are our friends."

U.S. officials say there are no more than 50 al Qaeda fighters in Afghanistan. In February 2008, I was kidnapped in Pakistan by the Taliban.

"Not a shot would be fired in Afghanistan without Pakistan's approval," my jailer told me. He told me there were many al Qaeda fighters there. They married local women.

I believe, based upon my experiences over a period of 30 years in the region, that Hekmatyier and Haqqani are tied to the Pakistani government. Haqqani especially is still tied to al Qaeda.

Ex-Militant: Pakistan supports terror groups

U.S. official: Pakistan still tips off militants

Why won't Pakistan dump the Islamists?

Al Qaeda is comprised of foreigners living in an alien land, and cannot operate independently. The question is, after the death of bin Laden, will those who know where al-Zawahiri is hiding, allow him to try to attack the U.S.?

The threat is still very much there, but I think an attack, if it comes, will originate in Yemen, or Europe.