Who will chair the Joint Chiefs of Staff?

Before the year is up, there will be a major turnover in the leadership of the U.S. military. Defense Secretary Gates is telling anyone who will listen that he will leave in "months," Admiral Mike Mullen, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, is scheduled to retire this fall, and General David Petraeus is expected to rotate out of Afghanistan by the end of this year. Who will replace them is the most popular guessing game at the Pentagon.

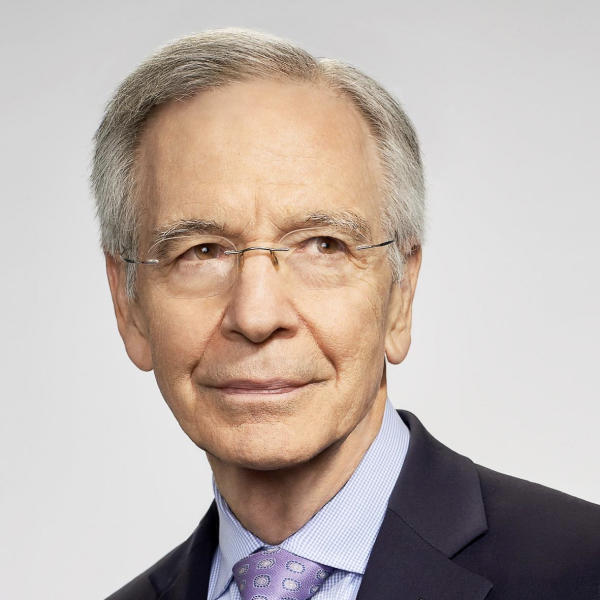

General James Cartwright, the current vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (the number two job in the military), is widely expected to succeed Mullen as the next Chairman, but there's a problem - an investigation into his relationship with a female Marine captain on his staff. An anonymous caller alleged that he was having a romantic relationship with the woman, who served as his aide de camp. (I have chosen not to use her name because she is still a junior officer far removed from consideration for a senior position.)

The resulting investigation by the Department of Defense Inspector General found no evidence of a romance but did conclude he had an "unduly familiar relationship" with the aide and raised questions about Cartwright's leadership.

A heavily redacted copy of the investigation released to CBS News under the Freedom of Information act, concluded that "Gen. Cartwright's failure to correct behavioral shortcomings on the part of (his female aide) was inconsistent with established leadership regulations" and recommended that the Secretary of the Navy (who has administrative control of Cartwright since he is a Marine) "consider appropriate corrective action." Those findings were ultimately rejected by the Secretary of the Navy, cleared Cartwright of any misconduct.

Most of the unredacted portions of the Inspector General's report deal with a trip to the republic of Georgia in March 2009, when, according to the report, "Gen. Cartwright spent several hours alone with (the female aide) in his (hotel) room in Tblisi between 11:00 pm and 5:00 am . . . in part for purposes unrelated to official duties."

According to the report and to interviews, Cartwright went to bed at the end of a long day and the rest of the staff adjourned to the bar. A message came in from the National Military Command Center that Cartwright needed to urgently review a classified document. She and another staff member came up to his room to set up secure communications with the Pentagon but were unable to do it. One person described her as "coming in and out of consciousness" but couldn't tell whether it was due to drink, stress or fatigue. Someone else set up the machine and while Cartwright worked on the document she fell asleep at the foot of his bed.

Cartwright testified that other staff members were constantly coming in and out and that he was alone with her for no more than 15 minutes. His staff asked Cartwright if he wanted them to carry her back to her room and he said, no, let her sleep.

A second incident occurred at the Alfalfa dinner in Washington, an annual gathering of big wigs. His female aide accompanied Cartwright to the dinner and waited for him in a holding area where she had too much to drink and got in an argument with a Secret Service agent. When the dinner was over, Cartwright saw that she was drunk and told his security detail to take her home so she would not have to drive herself.

In both cases, the aide got drunk and Cartwright let her get away with it. Or, as the report puts it, "Gen. Cartwright witnessed (her) questionable conduct in both Tbilisi and at the Alalfa dinner, but chose not to directly confront or correct (her) behavior. . . It is reasonable to conclude that Gen. Cartwright allowed the 'bonds of personal friendship' to deter him from dealing with (the aide's) shortcomings 'promptly and with sufficient severity.'"

The Secretary of the Navy, former Mississippi governor Ray Mabus, reviewed those findings and rejected them. "I do not agree with the conclusion that General Cartwright maintained an 'unduly familiar relationship' with his aide, nor do I agree that General Cartwright's execution of his leadership responsibilities vis-à-vis his aide . . . was inconsistent with . . . leadership requirements." In an interview, Mabus told me that he found nothing in the report that would disqualify Cartwright for the Chairman's job.

In the civilian world, the relationship between Cartwright and his aide would qualify as water-cooler conversation, but in the military, which revolves around "good order and discipline," it merited a full blown investigation. Officers who witnessed it thought her behavior was unprofessional and faulted Cartwright and his executive officer for not taking a harder line with her. Part of it seems to have been her personable style - calling senior officers "babe" or "hon," touching them on the arm when she spoke to them. Some members of Cartwright's staff tried talking to her about it, but she shrugged them off, perhaps because she knew how valuable she was to Cartwright. He described her as the best aide de camp he had ever had.