White-collar crime prosecutions hit lowest level in 33 years

- New data show a major drop in the number of white-collar criminal cases being brought by federal prosecutors.

- While the Trump administration is bringing fewer cases, the falloff is part of a longer trend that started in the Obama years.

- One expert said there likely is some "serious corporate crime going on" that continues being unpunished.

Federal prosecutors under the Trump administration are on track to bring the fewest number of white-collar criminal cases this year in at least 33 years, government records show.

White-collar prosecutions are down 8.5% from a year ago, to 4,973, and they are half what they were eight years ago, according to the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, a research center at Syracuse University that tracks federal data,

What's more, the white-collar caseload represents just over 3% of the 170,487 overall federal prosecutions that have been brought so far in the 2019 fiscal year that ends Sept. 30. Eleven months into fiscal 2019, the number of white-collar cases is expected to be the lowest annual total ever recorded in TRAC's database,which goes back to 1986.

"It's not just generally down," said Susan Long, TRAC's co-director. "The pattern of white-collar prosecution is a whole lot lower than they used to be."

In the 1980s and 1990s, the number of white-collar prosecutions regularly neared 10,000 a year. In the past three years, though, the number of cases has not topped 6,000.

While Trump administration officials are generally seen as more focused on immigration crimes than corporate wrongdoing, and the administration has said it doesn't want multiple federal agencies piling onto the same corporate criminal cases, Long noted that the white-collar decline precedes Donald Trump.

Federal white-collar prosecutions reached a high in 2011 under President Obama and have been dropping ever since. In fact, the annual numbers under the Trump administration are not that much lower than the number of cases brought in the final years of the Obama era.

"It's a matter of resources and staffing and competing priorities," Long said.

Take out immigration cases, which often get prosecuted as identity theft, and the number of white-collar cases would be even lower, she noted. Of the overall drop, however, "It is not something that a lot of people have noticed," she said.

John Coffee, a Columbia University Law School professor and expert on white-collar crime, said the drop-off in prosecutions may simply be a sign of how far we are from the financial crisis. Public outcry against corporate wrongdoing — higher in the early part of this decade — has died down.

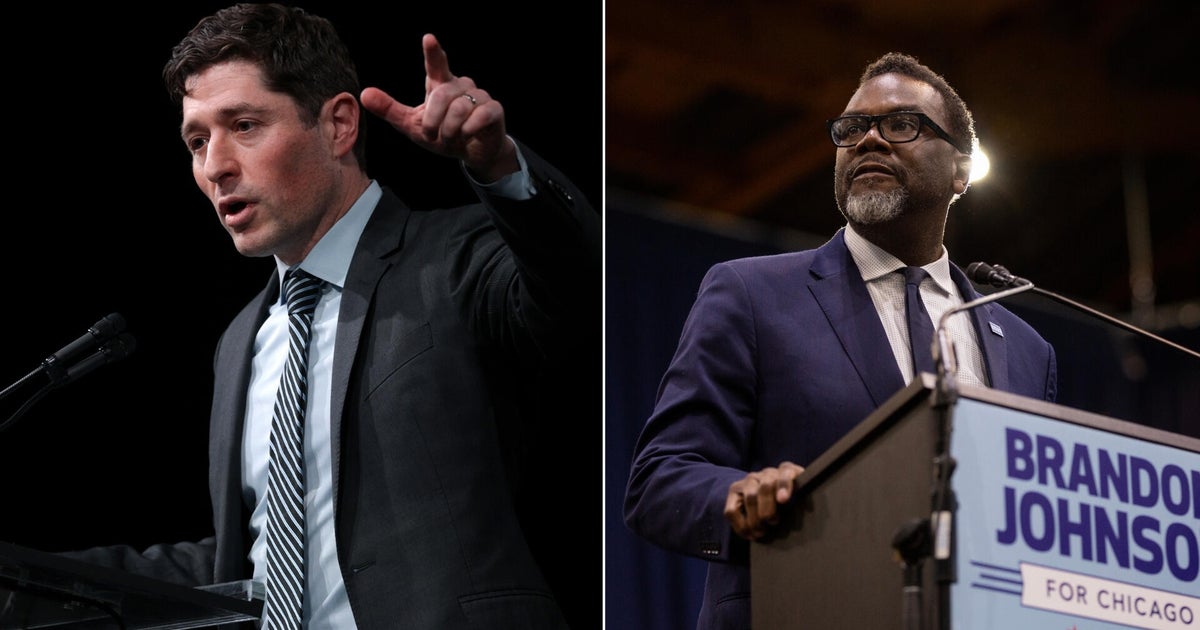

Brandon Garrett, a professor at Duke Law School and author of "Too Big to Jail," prefers to track punishments for white-collar crime rather than just the number of cases being brought. He said fines against corporations dropped dramatically in the second half of 2017. "If you look at the past 18 to 20 months, there is no comparison to the Obama years," Garrett said.

While it is possible there is less corporate crime than there used to be, Garrett's guess is the falloff is a matter of enforcement. "My sense is that there may be some serious corporate crime going on that is just not being punished," he said.