Which party is extreme? Depends on who you ask

As members of the 113th Congress went back to their districts for the August recess Friday, they headed out to a country collectively frustrated with its performance; one that says it wants compromise and thinks Congress has put aside efforts to help the economy in favor of political maneuvers, but also places where partisans view each other with great suspicion. That makes compromise even harder.

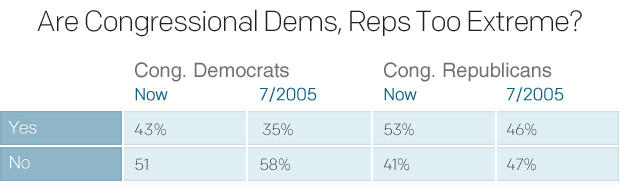

In the latest CBS News poll we noted more Americans think the congressional parties have become "too extreme" in their political views -- it's part of the reason so many are frustrated with Congress.

But what's driving that? Only some of it is from centrist Americans increasingly fed up with polarized parties -- most of it is actually driven by partisan Americans, who overwhelmingly see the other side as extreme. And that's not good news for the majority of Americans who want to see Congress compromise. When a representative's base voters don't think the opposition is even reasonable, then why shouldn't he or she stand firm?

The "too extreme" in their views tag was hung on congressional Democrats by 43 percent of Americans, higher than 35 percent back in 2005, and on Republicans by a majority of 53 percent, up from 46 percent in 2005.

But it's the partisan breaks on this that jump out: seven in 10 (69 percent) Republican voters think congressional Democrats are too extreme, and Democrats return the favor equally, with 69 percent saying congressional Republicans are too extreme.

Compared to partisans, independents actually don't appear stuck in the middle: just 29 percent of them see both parties as too extreme. Independents instead tend to pick only one of the parties as too extreme, so this isn't really a case of an alienated center watching both parties move further away. (And it also squares with the fact that many people who call themselves independent do in fact lean to one side.)

So for legislators who have to answer to voters back home, it's often who you're making the deal with that can cause them political problems. Americans want deals and compromises in principle, and from both sides -eight in ten say they'd like to see more of it. But when those Republican voters back home see congressional Democrats as too extreme, and vice versa for Democratic voters, then members to who cut deals across the aisle are bound to face suspicion: has that extreme other side really changed its stripes? Did our side really get more than we gave? And it's easy to see why activists on both sides are turned off by the very thought of cooperation with another party that's so (seemingly) out of touch.

Having said that much of this is driven by partisans, we should also note that the increases here from eight years ago come a lot from independents. (The partisans being somewhat locked in.) The percent of independents who say one party or the other is extreme has risen and both are taken to task today: 43 percent of independents now say congressional Democrats are too extreme in their political views for their taste, up from 36 percent, and 54 percent now say that of congressional Republicans, ticked up from 49 percent eight years ago.

These perceptions aren't strongly correlated with the demographic groups that vote for the parties, either; ideology and political positioning matter more. Women are not more likely than men to think the Republicans in Congress are too extreme; there's no gender difference (both say so). Conservatives and tea party supporters are faster to say Democrats are extreme.

And while this sentiment measures the caucus' political views, part of it is likely driven by the cues Americans take from a gridlocked process, too. Most - including most independents - think that when the parties oppose each other it's more often about them finding political advantage than it is true policy disagreement. And people who see one party as too extreme in their political views are also more likely to suspect political motives - not real disagreements - when the two oppose each other.

Each party can have a campaign interest in painting the other side as too extreme in its stances, of course, a tactic that's gone on throughout American political history, so this doesn't just come from the grassroots up; it permeates the rhetoric in both campaigns and legislative battles and it appears to have seeped in. It is especially impactful in lopsided, safe partisan districts, too, as we've shown, where a member needs to make sure the base is behind them.

Something to keep in mind as we watch the August recess; this year's town halls and constituent meetings. Voters of all stripes overwhelmingly say they want compromise - including from their own party. But remember that many representatives, and many of their constituents, tends to think the other side has a whole lot further to go than they do.