Which countries will a weaker yuan hurt most?

The Chinese yuan dropped for the third consecutive day on Thursday, bringing its loss to 3 percent against the dollar this week. Overnight, Beijing authorities tried to stabilize the situation by saying the currency didn't have much reason to fall further. They also dismissed talk Beijing was targeting a 10 percent devaluation.

Whether this was truth or conspiracy remains to be seen. But it's worth remembering that the People's Bank of China initially described Tuesday's revaluation as a "one off" move, and that's already been disproven.

Analysts and economists are now busily trying to figure out which countries will be worst hurt by the currency drop -- which looks like it could be an opening salvo in a mercantilist-style currency war, a last ditch effort to reinvigorate China's economy by spurring exports (which, not coincidentally, dropped sharply in July at a 8.3 percent annual rate).

Americans should be comforted by the fact labor productivity and cheap energy, as well as years of depressed wage growth, have greatly increased U.S. manufacturing competitiveness. An analysis by Boston Consulting Group last year found that manufacturing costs were only 4 percent cheaper in China vs. the U.S.

A recent update, taking into account shifts in currency values (mainly, the dollar's rise) found that foreign exchange fluctuations didn't meaningfully alter this takeaway. "The underlying trends that have driven the improvement in U.S. cost competitiveness over the past decade have not changed," according to BCG's Justin Rose.

"Manufacturers know that sharp gains in the dollar can quickly reverse," Rose said. "So they are far more likely to focus on trends in wages, productivity, and energy costs when making long-term decisions over where to locate plants."

Put simply: The U.S. is looking pretty good.

The same can't be said for China's other major trading partners. David Rosenberg at Gluskin Sheff looked at China's main exports and compared them to other countries focusing on the same things. He found China primarily exports electronic equipment, machinery, furniture, vehicles, clothing, medical/technical goods, plastics and iron/steel products.

Germany had "the most vulnerability by far in this sense," according to Rosenberg, with the two countries competing in practically every export category. Following Germany were Italy, France and the Netherlands. India was vulnerable in clothing, as was Turkey. Mexico had exposure in furniture, machinery, cars and electronics. And Japan was vulnerable in cars, machines and technical equipment.

Still, there are risks.

Mainly to the health of the global economy and markets, if one considers the currency devaluation as a desperation play. Sarah Boumphrey at Euromonitor International finds that Asian economies near China including Hong Kong, Taiwan and Vietnam are most at risk of economic weakness should a "hard landing" scenario play out.

Oxford Economics estimates that a 10 percent devaluation would have a "small positive effect on Chinese GDP, but is deflationary for other countries." The Federal Reserve, in this scenario, would likely delay its first interest rate hike beyond September, keeping long-term U.S. bond yields lower for longer.

In Oxford's downside scenario, Chile would be hit hardest, suffering a 5 percent GDP loss relative to baseline in 2017. The U.S. would suffer a 1.5 percent loss in foregone economic growth.

Long-term implications revolve mainly around the accumulation of dollar-denominated debts in the region. As China devalues, other countries will be tempted to follow. Indeed, Vietnam has already widened the trading band on its currency to 2 percent. This will make repayments more difficult and will make default events more likely.

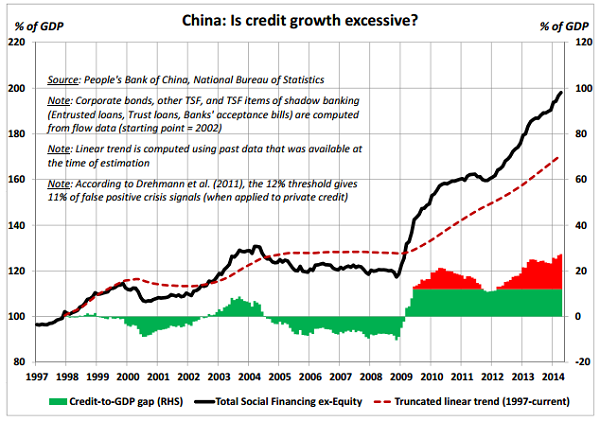

The chart above from the Banque de France shows just how extreme China's credit binge has been. According to Hans Redeker from Morgan Stanley, short-term dollar liabilities in China reached $1.3 trillion earlier this year -- equal to nearly 10 percent of Chinese GDP. Historically, in his words, this level of foreign indebtedness in emerging markets has been a "perfect indicator of coming stress."

A repeat of the Asian financial crisis of the 1990s, if that's where we're headed, would hurt pretty much everyone.

Gluskin Sheff's Rosenberg dismisses the comparison (China's currency was devalued 33 percent in 1994), and he doesn't believe China has launched a currency war, either.

First, he thinks the devaluation was merely a market reform effort to help encourage global acceptance of the yuan. Second, the Chinese government is mindful of its dollar-denominated debts. Third, a deeper devaluation would trigger capital outflows and destabilize sensitive Chinese markets. Fourth, a floating exchange rate would allow the central bank to cut interest rates to stimulate growth.

And finally, a weaker currency works against Beijing's stated goal of rebalancing the economy away from export dependence toward a consumer-focused growth model. The bottom line: Fears over what China has done are "way overblown."