When is a voter not a voter?

When is a voter not a voter?

It might sound like a silly riddle, but it's the rather serious business pollsters and campaigns are engaged in right now. The answer may tell us all we need to know about these midterms.

Republicans are often showing bigger leads among "likely" voters - the group that polls expect to actually show up - than among the wider group of all registered voters. In many recent polls, in a lot of Senate battleground states, that difference between likely and registered change a race from what can look like a toss-up to one where Republicans might pull away. In the national House vote the GOP lead is larger among likely voters (+6 ) than it is among all registered voters (+4) from our latest CBS News poll. (Though Republicans are expected to keep the chamber in any case, for a host of reasons.)

This is hardly just a polling matter or confined to election forecasts. It describes a more important - maybe the most important - political reality right now: Democrats probably have to either match Republicans' excitement, or find a way to turn out their base despite a lack of it, if they're to keep the Senate. And they have one month in which to do it (maybe less, because of early voting). It's a measure we've been watching all year: Republicans were eagerly eyeing November all summer.

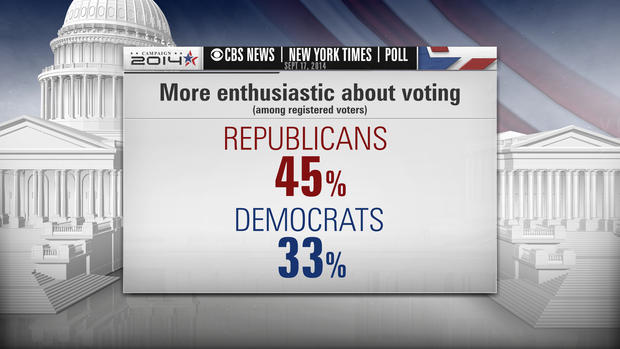

The enthusiasm gap shows the percent of each party who say they're more enthusiastic about voting this year than usual. 45 percent of Republicans say they're more eager this year, while 33 percent of Democrats describe themselves as such.

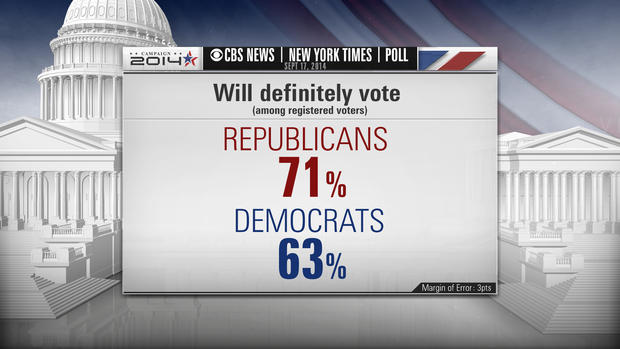

Now couple this with a more direct measure of turnout: voters who say they are "definitely" going to vote, versus those just "probably" going to vote. The latter of course implies far more certainty. In the latest national poll 71% of Republicans describe themselves as definite, while 63% of Democrats are.

Never mind, for a moment, the models or forecasts, from this one could just take voters at their word and estimate more Republicans would vote. We see similar differences between registered and likely voters in many polls right now.

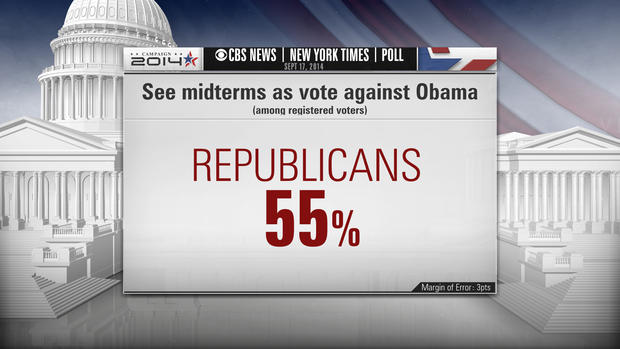

What's behind this? For Republicans, the number one reason is President Obama. He isn't on the ballot, but most (55 percent) say they view these midterms as a chance to cast a vote against him.

Historically, this isn't unexpected or even unusual. In the 2006 midterms when the Democrats retook Congress, 36 percent of all voters said their congressional vote was motivated by their opposition to President George W. Bush, and 93 percent of them went on to vote Democratic. So it can work both ways. Going back further, midterms have almost always been a bane to sixth-year presidents (with a notable exception for President Clinton in 1998) the theory being that by that time, core voters have either gotten what they wanted and are a little more complacent, or else - and more often, if we're being cynical - they're disappointed and stay home just the same.

Although Mr. Obama remains popular with his own base (he still has a 69 percent approval rating with Democrats) his low overall approval and unpopularity with independents (just 36 percent) means Senate campaigns aren't eager to have him come in to speak or rally that base, partly for fear of alienating the rest of the voters they need to persuade. And so many Democratic Senate candidates' ads - in races from Kentucky to Arkansas to Alaska - have stressed differences with, never a connection to, the President.

Democrats, for their part, say this election isn't entirely about the president, but rather that they care mainly about the economy. This, too, may turn into a turnout challenge. Most voters don't think the economy is good and few think it is getting better. That's particularly true for independents, which could effectively take that campaign issue off the table for Democrats, as it's tough to motivate voters to come out and reward a recovery that they don't feel is happening.

From a polling standpoint, there are years of data and plenty of good reasons to consider enthusiasm and expressed intention when considering what the final electorate might really look like. Midterm electorates always have lower turnout (around 40 percent of eligible voters) than presidential years (closer to 60 percent of those eligible) not coincidentally because the media attention and campaigning in the latter activates far more voters.

Attention and interest matter because voting takes effort. There's cognitive effort: you have to spend time learning about candidates and issues and make decisions. Even for a committed partisan planning to follow the party line, there's still an investment in learning those candidates' names (hence campaigns but such emphasis on building name identification early on.) And there's physical effort, and time. You have to go stand in line - sometimes, for hours - or drive out of your way to find an early voting spot or pick up an absentee ballot and fill it out. The recent rise in early and absentee voting has clearly helped Americans whose lives are busier-than-ever (more than a third of all ballots were cast that way last cycle) but it's still a commitment, even if you do it in October.

In voting, as with many things in life, commitment often goes hand in hand with interest.

It's also borne out when people with more time to spare, as well as more interest, show up in bigger numbers. It's why seniors, for example, many of whom are retired, vote in higher percentage numbers in midterms then younger age groups. (A demographic shift that in itself favors the GOP in midterms, as we explored earlier this year, because nowadays seniors tend to vote Republican.)

Of course, we can debate the degree to which parameters like enthusiasm or even expressed intention matter at all, too. People can change their mind from "probably" to "definitely." Those definitions could mean different things to different people. (One could imagine, in the abstract, that there is nothing at all you're "definitely" guaranteed to do next November!) Measuring enthusiasm also means looking at a state of mind that can change or vary. And one can argue that people don't need to be enthusiastic to vote; you might reliably vote out of a sense of civic duty, for instance, even if you aren't excited in any given year. (Likely voter models tend to use vote history, too, for this reason, though here again, that can't cover everything: the enthusiastic first-time voter has to be accounted for, too.) And comparing motivation year to year isn't easy, either. A given voter might have especially eager a few elections ago, with a candidate they liked, and just because this year doesn't measure up doesn't mean they'll stay home. This phenomenon could especially apply to Democrats these days, whose excitement about Mr. Obama was quite high when he was first a candidate. Polls that put too much stock in enthusiasm relative to voters' expressed intentions to vote might have fared worse in 2012, for instance, when Democrats did turn out but didn't report quite the same fervor as 2008.

It could also seem like this is just a fancy version of "it all comes down to turnout," but that can make it sound too much like turnout is a random effect that pops up on Nov. 4 than it really is. The decision of whether or not to tune in takes place in many voters long before that, and so at least some part of turnout can be anticipated long before Election Day by polling picking up these clues.

So the difference between a registered voter and one who is, effectively, not a voter - in other words, one that does not turn out - could well be the defining story of the midterms. And for Republicans, right now, the part of that equation looks like it's working in their favor.