What Trump's threat to close U.S.-Mexico border would cost

President Trump again threatened to close the southern border on Friday, or at the very least, "large portions" of it, next week if Mexico doesn't halt all undocumented immigrants from entering the country.

"If Mexico doesn't immediately stop ALL illegal immigration coming into the United States through our Southern Border, I will be CLOSING.....the Border, or large sections of the Border, next week," the president tweeted from Florida. "This would be so easy for Mexico to do, but they just take our money and "talk." Besides, we lose so much money with them, especially when you add in drug trafficking etc.), that the Border closing would be a good thing!"

It's unclear how Mr. Trump wants Mexico to stop the flow of migrants, and Mr. Trump has repeatedly threatened to shut down the border, as recently as Thursday, but he has yet to close ports of entry.

In November, the Trump administration shut down the busy crossing in San Ysidro, California, between San Diego and Tijuana, Mexico. It reopened hours later, but Mr. Trump's to "close" the entire 1,954-mile border with Mexico raise many questions -- including how realistic such a threat might be.

The U.S. has shut the border to passenger traffic and immigration only in spots, and for short periods, including after the Sept. 11, 2001 terror attacks (More on that experience in a moment.) So what impact would closing the U.S.-Mexican border have?

"An economic impossibility"

The San Ysidro crossing is the biggest passenger land port in the Western hemisphere -- just closing it alone would be hugely disruptive. Every day, an average of 120,000 commuter vehicles, 6,000 trucks and 63,000 pedestrians use the border gateway, many to go to and from their jobs in the U.S.

Sealing the entire border between the countries, meanwhile, would cause economic chaos. In 2017, about $558 billion in goods flowed across the U.S.- Mexico border in both directions, making Mexico our third-biggest trading partner for goods behind Canada and China. U.S. goods exported to Mexico totaled $243.3 billion, while trade in services accounted for another $58 billion.

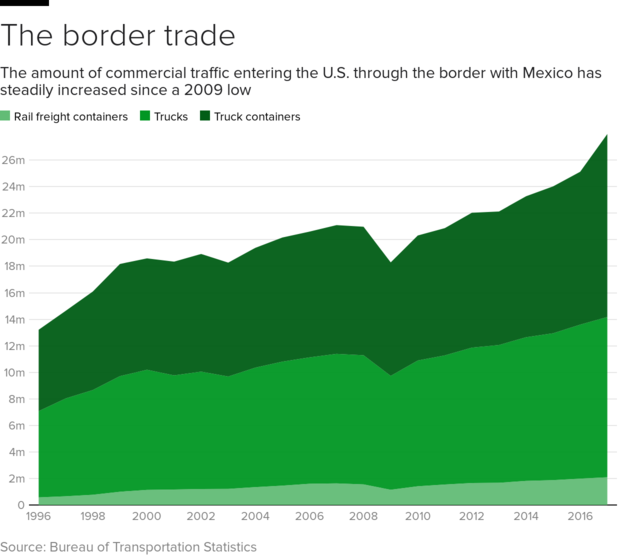

Trucks transport the bulk of goods: In all of 2018, $424 million -- 69 percent of all southern border freight -- crossed in from Mexico by truck, according to the U.S. Bureau of Transportation Statistics. That's up 10 percent from the amount of freight that crossed over in 2017. Two of the busiest truck border ports are Laredo and El Paso, both in Texas. Another $78 billion in freight crossed by rail, $67 billion by vessel, $17 billion by air, and $5 billion by pipeline.

Roughly 465,000 people also enter the U.S. each day through the various ports of entry at the southern border, according to a Wilson Center report. That's enough people to fill El Paso's Sun Bowl Stadium nine times.

"If you are thinking about a total shutdown of the border, then it's hundreds of millions of dollars a day -- maybe a billion," Duncan Wood, director of the Wilson Center's Mexico Institute, told CBS MoneyWatch. "It's an economic impossibility. Literally, the two economies would grind to a halt. Both economies are set up to depend upon cross-border trade."

The post-9/11 experience

Experts say the best analogy for closing the border with Mexico may be 9/11. The U.S. didn't seal the entire border after Sept. 11, 2001, instead enacting a "Level 1 Alert." That meant customs officers had to physically search every vehicle before allowing entrance.

"Usually you cross pretty promptly -- after 9/11 they went to this Level 1 Alert, and within about a day you had lineups of 12 to 18 hours at the borders -- both the U.S.-Canada border and the U.S.-Mexico border," according to Edward Alden, an expert on migration at the Council on Foreign Relations.

The backlogs "had an immediate effect in places like the auto industry," he said. "In a couple of days, GM and Ford were running out of parts they needed for production."

If Mr. Trump did order the closure of the southern border, costs for imported parts and goods would quickly spike, "from TV sets to washing machines to computers to avocados. Just run down the list of stuff that Mexico exports to the U.S.," Alden said.

Closed for how long? Actually, there's a study...

A 2011 simulation study to analyze threats including terrorism and deadly pandemics predicted that America's economy would collapse by nearly half if all U.S. borders were closed for a year. The study from the CREATE Homeland Security Center at the University of Southern California said cutting all imports 95 percent by shutting borders would in turn slice GDP by 48 percent.

However, if oil imports were allowed in and American workers "accepted real wage cuts" then the hit to GDP after a year would be closer to 11 percent, the study found.

Meantime, back in San Ysidro

San Ysidro, the busiest of the southern border's two dozen passenger land crossings, sees about 70,000 northbound vehicles and 20,000 pedestrians crossing each day.

Long lines and other inefficiencies at crossings like San Ysidro cost $7.2 billion in lost economic output and 62,000 jobs on both sides of the border, a 2007 study by the San Diego Association of Governments and California Department of Transportation found. The study even calculated that economic impact of an extra 15 minutes of border wait time: an additional loss of $1 billion in productivity and 134,000 jobs annually.

In all, about 6.8 million people live on the San Diego-Tijuana border, with a combined annual economic output of $220 billion, according to The Outline. Traffic at the port is projected to rise 87 percent by 2030.

An extended closure could cost the area billions, Paola Avila, a vice president at the San Diego Chamber of Commerce, told Bloomberg in November after the president again threatened to close the southern border. "The uncertainty of border closures occurring at any time is a substantial economic threat for our region," Avila said, adding the economies are "inextricably linked."

Still, the economies on both sides of San Ysidro are economically resilient when it comes to short, temporary closures, said Adam Rose, a professor at the USC's Price School of Public Policy and one of the co-authors of the 2011 CREATE report on total border closure.

Rose said such a shutdown would be a "significant inconvenience," but doesn't think it would seriously harm the U.S. or Mexican economies if the closure lasted no more than a few days. "Longer than that, it would be harder to make up the losses."

-- Additional reporting by Irina Ivanova and Grace Segers