What Monday's "shock day" sell-off could signal

The optimists are doing their best to dismiss the risk of the Greek financial crisis. They point out that the Greek economy is smaller than Louisiana's. They point out that unlike in 2011 and 2012, the European Union has built up defenses against financial contagion, including the European Central Bank's ongoing bond-buying stimulus.

In comments on Tuesday, President Obama said the situation in Greece "is not something that we believe will have a major shock to the system." This less than 24 hours after the U.S. stock market suffered its worst one-day loss of the year.

The evidence from internal stock market data suggests the optimists could be wrong. If history is any guide, the sell-off may get worse. Much worse.

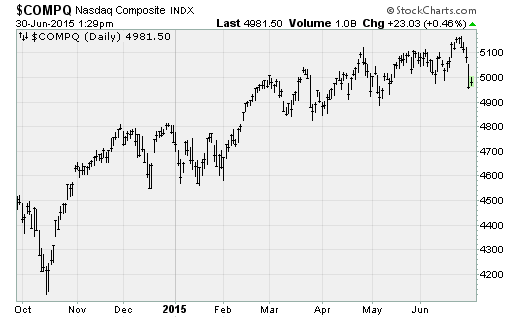

Monday's plunge was notable in that it ended months of market calm. The Dow Jones industrials index was trading near the 18,000 level first reached in December. The CBOE Volatility Index, a measure of fear among traders, had been in hibernation since February.

But Monday's decline pushed the Dow back below its 200-day moving average, a measure of medium-term trend, for the first time since October, while an exchange-traded fund that tracks the VIX posted its biggest one-day gain since 2011. In other words, investors felt a tinge of emotion they haven't experienced in a long time: Panic.

Jason Goepfert of Sundial Capital Research noted that the Nasdaq suffered a "shock day" sell-off -- a three-standard-deviation move coming on the heels of a 52-week high. Abrupt changes in market direction of this magnitude marked the last two bull market tops in 2000 and 2007, which is a scary precedent.

But before that, rising market volatility meant days like Monday came more frequently, and thus, they hold less predictive power about where stocks are headed. Yet it's notable that shock days also came before big market declines in 1984, 1987 and 1990. It's also notable that the market data suggest the shock days didn't mark an imminent low. Normally, they marked the initial phase of a more protracted pullback.

How bad could things get? History isn't destiny, but Goepfert calculates that since 1971 the median decline over the next week or so following a shock day was in the three percent to five percent range.

His advice to investors: "It almost always paid to let the initial shock pass before trying to step in."

Especially if this sell-off follows the more recent pattern: One year after the shock days of November 7, 2007 and January 4, 2000, the Nasdaq was down 42 percent and 33 percent, respectively.