Defining socialism: What it means and how it's shaping 2020

Socialism used to be a dirty word in American politics, but in today's Democratic Party, you'd hardly know it. One of the top contenders for the party's presidential nomination, Sen. Bernie Sanders, is a self-described democratic socialist. And the breakout star of the current Congress, New York Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, ran on a democratic socialist platform to defeat top House Democrat Joe Crowley in 2018.

But it isn't just lawmakers who have embraced the label. Young Americans, particularly those born after the end of the Cold War, say they want the U.S. to become more socialist. A recent Harvard Caps/Harris poll of 1,792 registered voters obtained by The Hill found 56 percent of 18 to 24-year-olds favor a "mostly socialist" system. The same is true of 48 percent of those aged 25 to 34. One Gallup poll last year even found Democrats prefer socialism to capitalism.

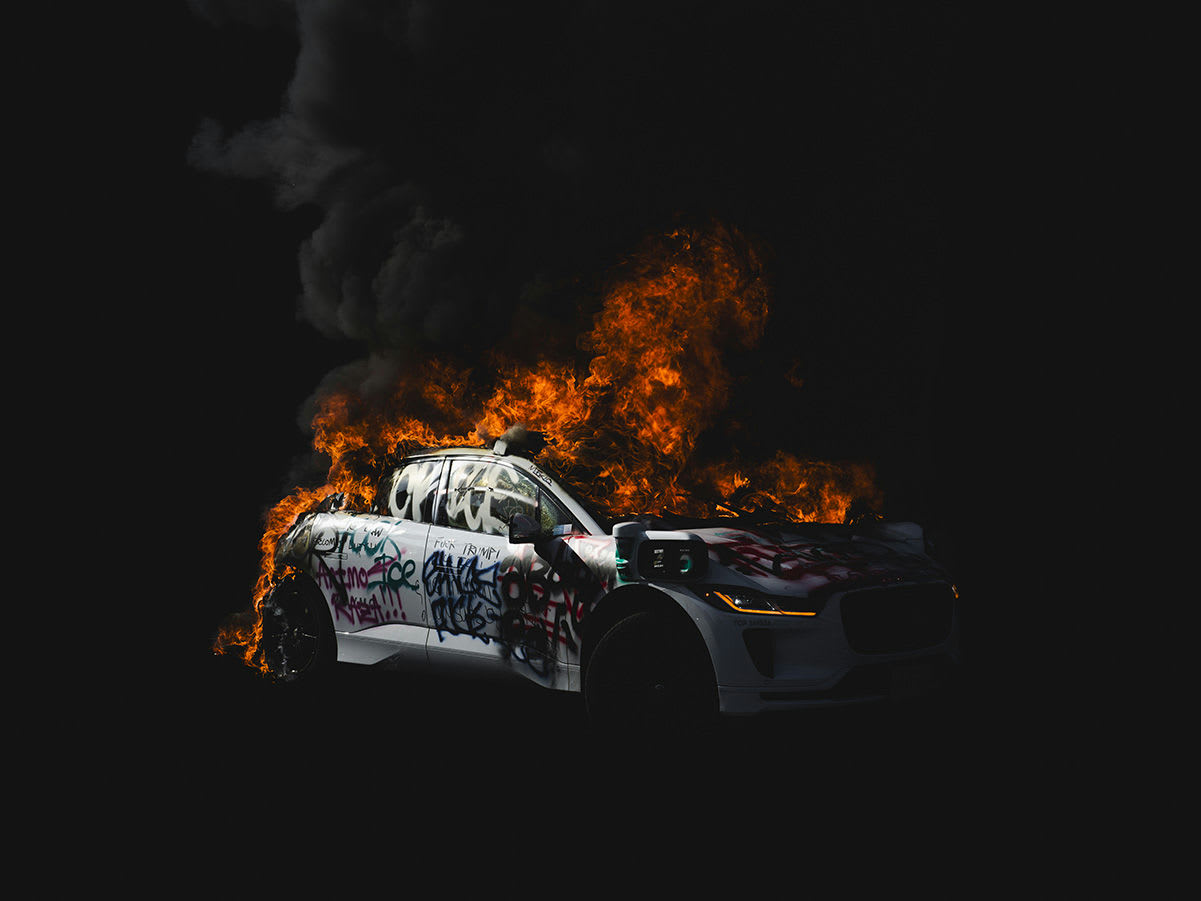

President Trump and his allies, however, are betting that most voters still aren't ready to see a socialist in the White House. In recent months, Mr. Trump has repeatedly insisted that a Democratic win in 2020 would put America on the road to socialism, a tactic that's become more noticeable during the administration's ongoing standoff with Venezuela's authoritarian socialist government.

So, why is the idea of socialism so appealing now? And, three decades after the Soviet Union's collapse, what does socialism even mean?

Defining socialism

Socialism was likely first used in a political context by followers of the 19th-century British social reformer Robert Owen. Traditionally, it's associated with the concept that the "means of production" should be both owned and operated by the state, although the 20th century saw the emergence of many divergent strands of socialism that often competed with each other.

"There are many different kinds of socialism," Michael Kazin, a history professor at Georgetown University who is an expert in U.S. politics and social movements in the 19th and 20th centuries, and who describes himself as a democratic socialist, told CBS News. "That's part of the reason why it's easy for the president to attack Democrats by linking them to Venezuela, which of course is not a socialism that anybody that I know of in the United States wants to emulate."

"But the original meaning of it is a society -- that's where it comes from -- which is socialized so that everybody benefits from it and one that is democratically governed by everybody in the society," Kazin said. "It's a utopian notion originally."

Socialism came to be heavily associated with the work of 19th century German economist Karl Marx and the emergence of labor unions. By the turn of the 20th century, socialist parties were represented in several European parliaments. And after Russia's October Revolution 1918, the first "socialist state" was established: the Soviet Union, which hewed to the idea of the state owning the means of production.

Unlike most of the rest of the world, the U.S. has never had a major socialist party. But it still always had its supporters, including a number of celebrities, trade unionists, and prominent intellectuals.

"This is not the first time that socialism has had a high profile in America. I mean 100 years ago, a little less than 100 years ago in the 1908-1918 or so period, you know there were many more socialists in America than there are now," including Hellen Keller and Charlie Chaplin," Kazin said.

From the beginning, American socialists fought over which form of socialism was the genuine article. Many of them originally embraced Soviet communism, although that became an increasingly marginal opinion among socialists as the Cold War began. Others remained socialists but were critical of the Soviet model and other examples of similarly repressive forms of socialism in places like China and Cuba, which led to the emergence of groups like the Democratic Socialists of America in the 1980s.

What socialism means today

Kazin said the socialism most Americans are embracing is what Europeans would call social democracy, a view associated with mainstream parties like the Labour Party in the U.K. and the SPD in Germany. This version, Kazin said, advocates "a much larger welfare state where everyone is pretty much guaranteed a place to live, a job, or at least good benefits if they can't find a job, health care that they can afford, which is subsidized by the government."

After decades on the fringes of American political discourse, the Democratic Socialists of America is enjoying a surge in membership and interest. Although still small compared to other political interest groups, it's ballooned from 7,000 to some 50,000 members since the 2016 election, according to organizers. Ocasio-Cortez is a member, as is fellow first-term Rep. Rashida Tlaib.

Chris Riddiough, a founding member of the Democratic Socialists of America who now serves as a DSA National Political Committee member, said DSA strives to represent a "big tent" of socialism. But at its core, she says, socialism entails a belief that the American economy treats people unfairly and must be put on a new course.

"In DSA we define our politics as a big tent of socialism," Riddiough said. "And that means our view is that there is not a correct line on socialism. But in general, we believe that it encompasses the idea of economic and political and civil democracy so that people have the resources they need to make it in the world. So we support things like Medicare for All, some of the recent child-care proposals, college tuition breaks, things like that. And we believe that the economy in particular over the last 20, 30 years or so has become increasingly undemocratic."

Most self-described socialists in the U.S. today don't want a government-run economy but an "economy where the government has a larger role to play in guaranteeing the basic necessities of life," Kazin said.

His point echoes arguments made by Sanders when he ran for president in 2016. When asked what his kind of socialism looks like in practice, the Vermont senator would point to Denmark and other Nordic countries, not Cuba or Venezuela. Comparing the autocratic socialism of underdeveloped countries to the kind that exists in wealthy democracies, Kazin argues, is like "comparing apples and coconuts." The human rights issues countries like Cuba and Venezuela are clearly problematic.

But Joshua Muravchik, a fellow with the World Affairs Institute who authored "Heaven on Earth: The Rise and Fall of Socialism," said that the European democracies that Kazin and Sanders point to as models "aren't socialist and they actually pulled back from socialism, and Sweden has a quite robust private sector."

"The point is that democratic socialists or social democrats were successful to a degree in creating what is usually called a 'welfare state,' which we also have in the U.S…but they achieved this only by abandoning socialism," Muravchik, a former socialist turned neoconservative and critic of the system, said.

"If you want to say that Denmark and Iceland have a 'version of socialism,' then you have to say that every democracy in the world does, too, because they all have one degree or another of welfare state. If they have a version of socialism, they also all have capitalism. Every democracy has a 'mixed economy.'"

Regardless of how the term is defined, it's clear that Americans have become more open to the idea of socialism. This is particularly true since the Great Recession and Sanders' 2016 campaign for president, which drove conversations about socialist ideas into the mainstream.

"I think Bernie Sanders entering the race in 2015 made it possible to talk about socialism and a lot of the policies that he was putting forward, and I think his entry into the race now also helps shape the debate," Riddiough said.

Today, even Democratic presidential candidates who eschew the socialist label – such as Sens. Kamala Harris and Elizabeth Warren – have embraced policies championed by Sanders, such as expanding Medicare coverage to all Americans regardless of age.

Such progressive policies — and socialism in general — are something the Republican National Committee will focus on in its messaging as the 2020 presidential cycle progresses. Mr. Trump already highlighted socialism in his State of the Union address, and socialism was a key theme in many speeches at the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) last week.

"The debate between capitalism and socialism will take center stage in 2020," RNC spokesman Steve Guest told CBS News. "The RNC will continue to spotlight all of the good news that is happening in our country thanks to President Trump's free-market approach. And, we will make sure Americans are fully aware of the Democrat 2020 candidates efforts to make their radical, far-left socialist policies the mainstream in today's Democrat Party."

What comes next

Perhaps the greatest divide in the approaching Democratic primaries will be deciding just how far left the party is willing to go. Polling indicates that the majority of Democratic voters want an electable candidate first and foremost, which may make them wary of socialist-endorsed proposals necessitating big tax hikes.

Sanders' Medicare for All plan would cost an astronomical $32.6 trillion, according to one study by the libertarian-leaning Mercatus Center at George Mason University. Even House Speaker Nancy Pelosi recently questioned how the nation would pay for Medicare for All, although proponents of the idea argue it would control costs in the long run.

"Thirty trillion dollars. Now, how do you pay for that?" Pelosi asked in a recent interview with Rolling Stone.

The Green New Deal proposal, a plan to transform the economy to combat climate change and dramatically expand the welfare state, would also cost tens of trillions of dollars. Top White House economic adviser Kevin Hassett recently estimated the plan would shave 10 to 15 points off U.S. GDP if implemented. And although the Green New Deal is championed by lawmakers like Ocasio-Cortez, most top Democrats have been skittish about embracing it in full.

"The 'Green New Deal' is a joke," Muravchik said. "If enacted we would get one year into it, and it would be repealed because it would be so disruptive to the economy."

Medicare for All and other social democratic priorities, such as free college, would be "harmful but less catastrophic, except for my grandchildren and your children who would be left to try to pay down the debt," Muravchik added.

Still, in a sign that the Democratic Party has moved decidedly left in recent years, some economic issues are likely to become a "litmus test" in the Democratic nomination, Kazin said. And Riddiough argues that while nothing is more important than defeating Mr. Trump in 2020, Democrats should not assume that a hard-left candidate couldn't win in the general election.

"I do think that's a concern," Riddiough said of Democrats choosing someone electable in the general election. "But I don't think it's a question of being too far left. It's more a question of, which candidate is going to be able to win over voters with their ideas?"