West Virginia poverty gets worse under Trump economy, not better

West Virginia has a growing poverty problem, and experts there who study the issue say Americans in every state should pay attention.

The Appalachian state is, along with Delaware, just one of two states where poverty rose last year, bucking the national trend of growing incomes and declining hardship, according to U.S. Census data released earlier this month. West Virginia's poverty rate climbed to 19.1 percent last year from 17.9 percent, making it just one of four states with a poverty rate above 18 percent.

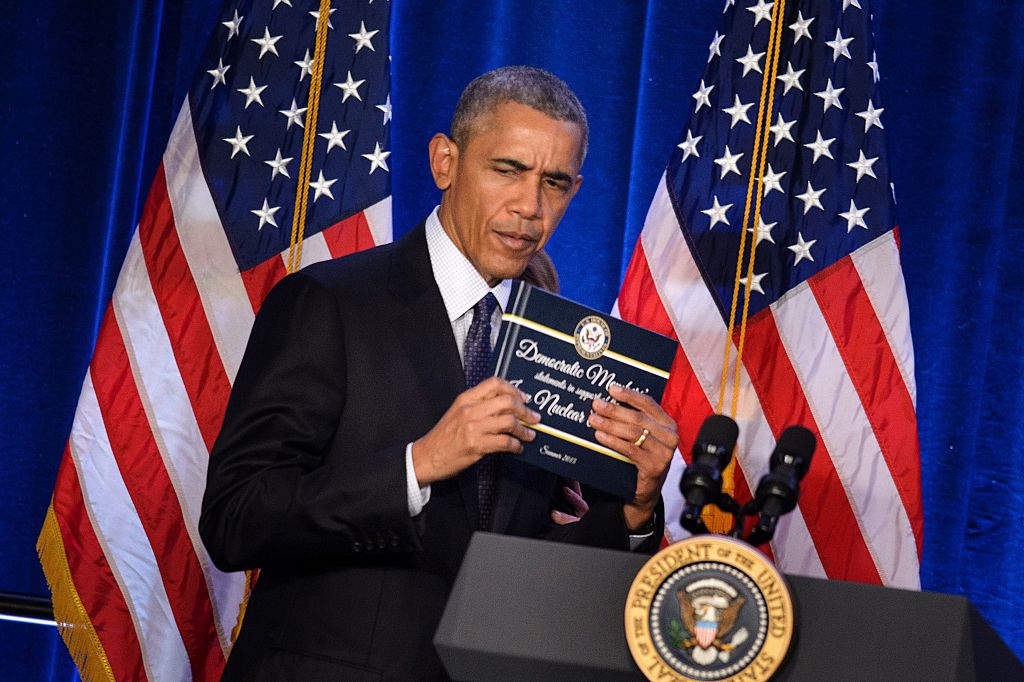

President Donald Trump plans to visit West Virginia on Saturday, when he's expected to tout his economic accomplishments. The president has said he's "very proud" of the state and claimed that he "turned West Virginia around." His administration has focused on reviving jobs in the coal industry, which has added about 2,000 jobs across the U.S. since Mr. Trump's inauguration.

Mr. Trump has boasted about the state's GDP growth, but its economy grew by 1.3 percent in the first quarter, or 37th in the nation and lagging the national rate of 1.8 percent, according to government data. It had fared better in 2017: up 2.6 percent for the year, tenth among the 50 states, compared with 2.1 percent for the nation.

Coal "is a potent message," but it overlooks the reality of West Virginia's economy, said Sean O'Leary, senior policy analyst of the West Virginia Center on Budget and Policy, a nonpartisan think tank. "The growth we've had is in low-wage industries. Folks who find jobs haven't found jobs that keep them out of poverty."

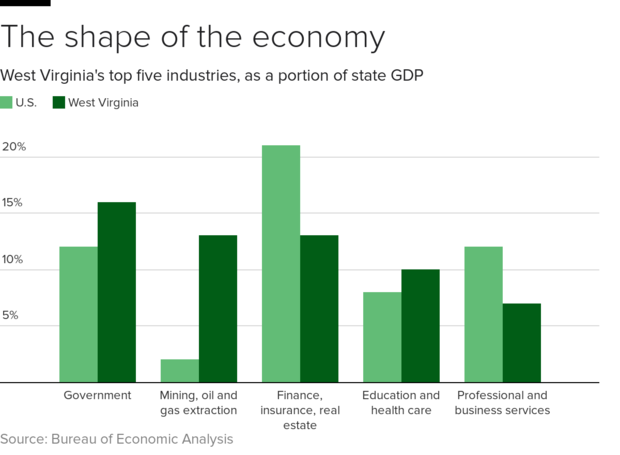

Jobs in low-wage industries have grown 14.5 percent since 2001 in West Virginia, compared with a decline of 2.8 percent in jobs that pay higher wages during the same time, according to the WVCBP's figures. The state has about 22,000 people employed in mining and logging, compared with 131,000 education and health care workers and 155,000 government workers, two of the biggest industries in the state, according to government data.

West Virginia's dismal trends point to an economic issue that's impacting states across the country: Workers at the bottom of the pay scale aren't benefiting from the growing economy. Their issues range from low pay to unstable and scanty work hours, which makes it difficult to earn a living wage. Almost one in four West Virginians is employed in a low-wage job, the WVCBP found.

"It's cashiers, retail sales people, service employees -- those are our fastest growing jobs, but those jobs don't pay very well," O'Leary notes.

At the Manna Meals soup kitchen, more people are coming in for nourishment, said its executive director, Tara Martinez. The Charleston soup kitchen served almost 10,800 meals in August, compared with about 9,700 in January.

"There's a direct correlation between the hopelessness and the lack of jobs," she said. "The jobs that are available are minimum wage and part time -- they don't have benefits. When you have that, coupled with the hopelessness of, 'How do I get out of this cycle?' and having to go to a soup pantry, it's like a hamster wheel."

The opioid crisis is another issue facing West Virginia, which Martinez said she believes is tied to low-wage jobs and a lack of opportunity. Her observations echo academic findings from Princeton economists Anne Case and Nobel Prize-winner Angus Deaton, who found rising mortality rates for less educated white adults in the U.S., which they called "deaths of despair."

And West Virginia plays directly into the issues highlighted by Deaton and Case. The state, whose population is 95 percent white, is frequently listed as one of the least educated states in the country.

About 21 percent of West Virginians between ages 25 to 64 has a college degree, according to the National Information Center for Higher Education Policymaking and Analysis. At the national level, about one-third of American workers have a college degree.

The post-recession economy has favored Americans with college degrees, providing them with both growing incomes and professional opportunities. But many who lack that credential have been left out of the recovery, as evidenced in West Virginia.

"People who don't have jobs or don't have any way out of this cycle, there's a hopelessness that overtakes them," Martinez said.

To be sure, West Virginia is coping with other hurdles in its battle against poverty, such as an aging population, higher rates of disability, and a small workforce compared with bigger states, such as New York or California. The state's small size -- just 1.8 million people last year, down 50,000 from 2010 -- means it's harder to lure employers to the state, O'Leary noted.

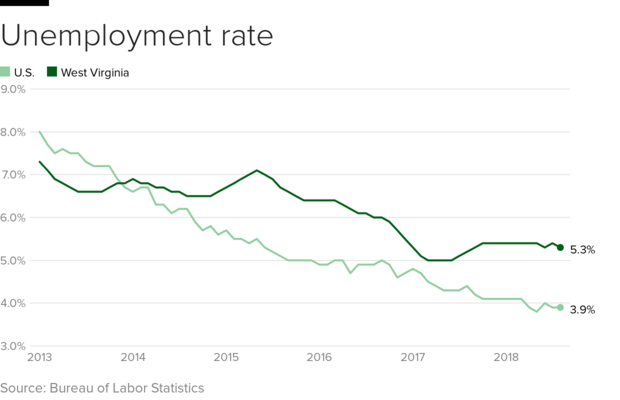

West Virginia had a net job loss of 26,000 from early 2012 to late 2016, according to a study from West Virginia University. And the state has the lowest labor force participation rate of all 50 states, at 53 percent.

Employment is growing slowly at a projected 0.7 percent per year through 2022, or below the national growth rate of 0.9 percent. At that rate, local employment isn't expected to reach its 2012 peak until 2021, the study found.

West Virginia's poor residents will face another burden beginning in October, when work requirements for food stamps go into effect across the state. Martinez said she believes the measure, which requires able-bodied adults without dependents to work, volunteer or receive job training for at least 20 hours a week to receive food stamps, will push more into poverty and ramp up demand for her soup kitchen's services.

"It's frightening and I'm worried and I'm doing everything I can to make sure our doors are still open," she said, noting that she expects demand for meals to rise by 30 percent. "It's going to be a lot of fundraising and pleading."

She added, "You have huge companies, corporations that do really well and make a substantial profit and paying their employees as little as possible -- and their employees are on food stamps or other benefits."