West Memphis 3: The cost of freedom

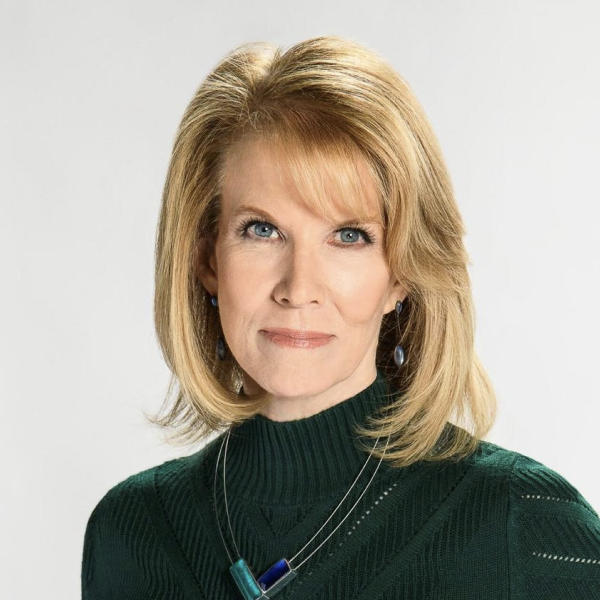

In their first television interviews since being freed from prison, Damien Echols and Jason Baldwin talk exclusively with "48 Hours Mystery" Erin Moriarty. Watch "West Memphis 3: Free" Saturday, Sept,. 17 at 10 p.m. ET/PT.

This is what justice in Arkansas looks like: On Aug. 19, 2011, Judge David Laser in Craighead County released three men who had spent the last 18 years in prison, one of them on death row. But as part of an unusual plea agreement, the three men -- Damien Echols, Jason Baldwin and Jessie Misskelley -- who insist they are innocent, had to first plead guilty to three counts of murder.

It struck more than a few observers in the packed courtroom that morning that the surreal spectacle had very little to do with justice. As one of the newly freed men, Jason Baldwin, later described it, "When we told prosecutors we were innocent, they put us in prison for life. Now when we plead guilty, they set us free!"

The county prosecuting attorney Scott Ellington's actions didn't help clear up matters either. He said publicly that he still believed these men were guilty of one of the most heinous crimes in the state's history: the brutal murder of three 8-year-old boys in 1993. And yet, he made them all sign a waiver promising not to sue the state.

The cases of the three men, known as the West Memphis 3, have long been the subject of passionate debate in the legal community. The prosecution of these men, teenagers when the crime occurred, was driven by a rush to comfort a community overwhelmed by fear and grief.

On May 5, 1993, three 8-year-old Cub Scouts -- Michael Moore, Christopher Byers and Stevie Branch -- went missing and were later found murdered, mutilated and submerged in a watery ditch. To local investigators, it seemed the work of a satanic cult and when a local juvenile officer suggested the name of Damien Echols, theory soon became fact. Echols, a local 18-year-old boy, was bright but troubled. Various problems with authorities led to a brief stay in a psychiatric hospital. Investigators were led to interrogate Jessie Misskelley, an acquaintance of Echols who reportedly has an IQ of 72. Misskelley, questioned by police for 12 hours, gave them statements that not only implicated himself, but also Echols and close friend of Echols, Jason Baldwin.

Misskelley -- who later recanted his confession -- was tried first and convicted of three counts of murder. He refused to testify against Echols or Baldwin so his confession was barred from use at their joint trial. Still, according to one juror's notes recovered long after the trial, the jury foreman added Misskelley's statement to deliberations. The jury convicted both Baldwin and Echols. Baldwin, like Misskelley, got life in prison; Damien Echols was sent to death row.

They might still be there today if not for a film crew that happened to be covering the case in 1994. The resulting documentary, "Paradise Lost," aired on HBO, highlighting the flaws in the case and trials. Since then, new witnesses and DNA tests of evidence at the crime scene have, not only supported the innocence of all three men, but have pointed to other people who were not investigated when the murders occurred. More important, the crucial theory of the case was, in large part, debunked by leading medical experts. The mutilation of the bodies of the boys, believed by investigators to be caused by knives as part of a ritual, was more likely to be the result of animal predation that occurred after the children were killed.

Despite the growing sense that the wrong men were in prison, their numerous appeals were continually denied by the Arkansas State courts, until last November. An appeal filed by Damien Echols convinced the state Supreme Court to order an evidentiary hearing on all the evidence in the case, new and old.

Most legal experts agree that the evidentiary hearing, scheduled for December of this year, would likely lead to a new trial for all three men. And that put the State of Arkansas in a tough situation. What if new juries acquitted the West Memphis 3? Faced with the very real possibility of new, expensive and embarrassing trials, state officials were willing to make a deal and Echols' attorneys came up with one: an Alford Plea.

An Alford plea, a rare legal maneuver, has been in existence since the U.S. Supreme Court ruled on it in 1970, but few defense attorneys want it and few prosecutors will allow it. It's a compromise, pure and simple. Echols, Baldwin and Misskelley would be allowed to continue to insist they were innocent, but they had to plead guilty. In return, they were given freedom and the State got its convictions. There would be no new trials. The deal almost fell through. Jason Baldwin, who wanted to be exonerated in a new trial, had to be convinced. In the end, he changed his mind to get his friend Damien Echols off death row.

And so in a bizarre hearing on that August day in Jonesboro, Ark., the three men went in front of a judge, and after announcing their innocence loudly, they went ahead and took a guilty plea. They are now free men, but may face limitations: in some states, they can't vote and could encounter prejudice down the road.

And what about the families of the little boys killed on that May day more than 18 years ago? Will they ever know what happened to their children? The state has its convictions; there is no incentive to re-open the investigation. DNA from the crime scene may someday yield new answers and new arrests, but until that happens...this is justice in Arkansas: a political compromise that saves money and face, but leaves everyone wanting something more.