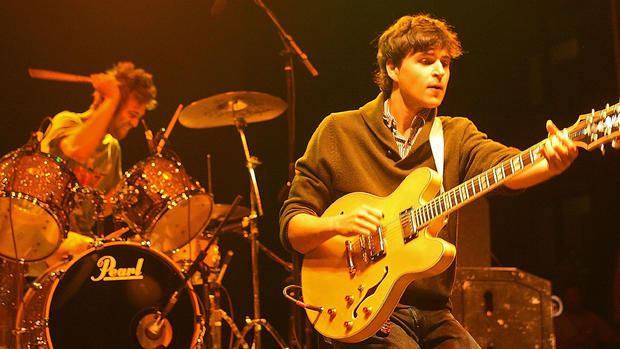

Web extra interview: Vampire Weekend's Rostam Batmanglij

(CBS News) Raised in Washington, D.C., by parents who fled the Islamic Revolution in Iran, Rostam Batmanglij began his musical education at a young age, as a performer and a mixer of sounds -- gifts which have now flourished in the success of his band, Vampire Weekend.

In this web-exclusive interview, Batmanglij tells correspondent Anthony Mason about his measure of what makes a good song, and why he's glad his music is NOT played on pop radio.

Anthony Mason: "You started playing music pretty early."

Rostam Batmanglij: "Yeah."

Mason: "How many different instruments do you play?"

Batmanglij: "I can usually make some sound come out of something (laughs), if I spend enough time with it. I guess my first instrument was the recorder when I was about five or six. But I really wanted to learn the flute and that's what I started learning, when I was seven."

Mason: "Wow."

Batmanglij: "And then I stuck with that for about seven years and I got very burned out, honestly, by the time I was about 14. I didn't want to ever have to play it again."

Mason: "Do you ever pick it up anymore?"

Batmanglij: "Yes, from time to time. But I think I was more interested in harmony, which you can't really do on the flute, as a 14-year-old. It was drawing me towards the guitar and the piano because, you know, they were instruments where you could play more than one note at the same time."

Mason: "How did you pick the flute in the beginning?"

Batmanglij: "I don't know exactly. It might have been because my older brother was learning the clarinet and I wanted to be a little bit like him. (laughs)"

Mason: "But not exactly the same."

Batmanglij: "Yeah."

Mason: "That's funny. So when did this interest in sort of mixing in music and creating things start?"

Batmanglij: "I started playing guitar when I was 14. My guitar teacher, he was one of those great people who wanted to teach you anything you want to learn. And at the same time, he would push me. So he could play any kind of guitar -- rock guitar, classical guitar, jazz. And the first day, I just wanted to learn, you know, whatever was on alternative radio.

"So I was like, 'How do you play this Radiohead song? How do you play Counting Crows?' That's what I was listening to at that age. And then, after I got through those, he would say, 'Okay, now it's time for you to learn a Jimmi Hendrix song.' And then he would say, 'Now, it's time for you to learn, 'The Girl From Ipanema'. (laughs)

"And then I think slowly I just became more interested in, how were these songs being put together? I remember, it was a big deal when I got my first four-track, which let you record four different tracks on top of each other."

Mason: "Right."

Batmanglij: "And I started sort of laying guitar parts. That was kind of the beginning of being interested in recording. And then, from there I convinced my parents to let me have a drum set in my bedroom."

"I dunno why they agreed to do it. Might have made their lives kind of tough for a while. (laughs) But once I started to have these instruments in my room, I was kind of teaching myself how to put recordings together and teaching myself how to play and teaching myself how everything fit together."

Mason: "You were a one-man band."

Batmanglij: "Yeah. What's interesting about Vampire Weekend, everyone in the band, except for me, had a band in high school in which they were the lead singers. And I'm the one who never had that experience. I was more interested in recording music. Having a band didn't interest me in the same way."

Mason: "It sounds like you didn't need a band. You were doing it all yourself, anyway. (laughs)"

Batmanglij: "I guess, yeah, maybe I was just interested in the recording process, just somehow I was drawn to it.

"[My parents] were really supportive, actually. We had a neighbor when we were really young, and my dad asked our neighbor, 'Our kids want to learn instruments. What do we do? Do we just buy the instruments and leave them in the house? What if they stop playing them after a week?' And this neighbor said to my dad, 'Just buy them. Let them be there. The kids will learn them. You know, it'll be positive.' And so my parents took his advice. So if there was anything I wanted to learn, they were happy for me to explore it.

It's interesting because neither of my parents play instruments. They both love music, but neither of them are musicians. Somehow, I was drawn to it.

Mason: "What would you do with the stuff that you mix together in your room?"

Batmanglij: "Well (laughs), I'd play it for my cousins. I'd play it for my parents. I played it for my guitar teacher, and I remember what he said. He was like, 'Oh. That's very special, what you're doing there.' And I didn't think so. I thought it was, you know, it was whatever. He's like, 'You know, not everyone can do that.' He kind of encouraged me in a way that was pretty important."

Mason: "It's funny how, like, a sentence like that from a teacher somewhere along the line can actually change a lot."

Batmanglij: "It does, yeah."

Mason: "Because it changes the way you think about yourself."

Batmanglij: "That's true."

Mason: "Because you're like, 'If he sees something, maybe there IS something and it's not just me in my head.' "

Batmanglij: "You know, I spent a long time devoted to music, but it wasn't until about halfway through college that I feel like I something clicked for me and things changed. I dunno. I felt like I was making music that I was proud of for the first time, proud of in a different way than I'd been proud of before. I felt like I was starting to have a little bit of an identity musically. And that was always really important to me.

"Since I was a kid, like, I really wanted to be a painter. What I loved about Basquiat was that his style was so distinct. Like, you knew it was him. You could see the arc of his hand, you know? It was preserved. It was intact. And that was important to me, to make music that's distinct. That's still important to me, to this day: that people be able to hear, 'Oh, like, I get it. I hear you in that,' you know?"

Mason: "Uh-huh. When did you start wanting to be a painter and when did you give it up?"

Batmanglij: "I never really gave it up. But no, I guess I kind of did give it up! (laughs) Since I was really young, I used to draw in front of the TV for hours. Drawing was something that my parents would encourage me and my brother to do, and we would have, you know, family portrait contests where everyone in the family had to draw a portrait of everybody. At some point, I think I realized I didn't want to devote myself to painting.

"I did see an interview with Brian Eno recently. He was at art school in the '60s or the '70s, and he was saying that at that time, the recording studio was just kind of being invented and as a painter, he went there. And he realized that recording music was sort of like painting with sound. So I think there is a connection with people who like visual art and people who like recording music. There is some kind of a connection there."

Mason: "So if you weren't in a band, what were you envisioning doing with all of this?"

Batmanglij: "Well, I thought about being a contemporary classical composer. That was something I really, seriously thought about. But I dunno. That world didn't really draw me in. On some level, I realized that music had this power. And that part of that power was connecting with people and connecting with traditions. And I felt like, in some ways, the tradition of classic music is dead, it's a dead tradition. Whereas, the tradition of writing songs is very much alive."

Mason: "And you wanted to take one into the other somehow? Because you've done that."

Batmanglij: "I want -- yeah, I wanted those two to exist with each other. I think I was just drawn to songs as the medium for whatever you want to express."

Mason: "Because listening to your music the first time, what's so striking is the eclecticism of it."

Batmanglij: "Yeah."

Mason: "All these things thrown into a pot. And what comes out is this still very accessible music. Is that what you were aiming for, or do you even know what you were aiming for?"

Batmanglij: "I think it's the result of maybe, as a kid I was never exposed to music that was so far out that I would -- I don't know. There's some music that I really respect that you couldn't call accessible. And I think I've realized that I'm not really capable of making that kind of music, even though I love it. But there is some limit to the kind of music I'm capable of being a part of, the kind of music I'm capable of writing.

"When I was at Columbia majoring in music, we studied 12-tone music and I had to listen to so much of it and it would just pass right through me. I wouldn't feel what I wanted to feel for music, listening to 12-tone music.

"So I think maybe it's the result of just growing up mostly listening to pop songs and listening to classical music, which, to me, classical music and pop songs, they're not that disparate. I think of them kind of in the same world. But there is this other world of music, and there's some of it that I really respect. But I recognize that I'm not capable of being a part of that world of music, like atonal music."

Mason: "Why do you think of classical music and pop songs as being [not that disparate]?"

Batmanglij: "Well, they're both accessible. They both have idioms and they have sets of rules [that] they conform to. And if you understand some of the basic rules, they are very similar. They share a lot of the same kind of principles."

Mason: "I remember the first time I heard your first album and thinking, 'This is really catchy, almost in spite of itself.' (laughs) There was the classic stuff that comes in, which sort of surprises you. There's the African stuff, which is obviously catchy. But there was a lot going on. It was just a really interesting kind of soup that still, you know, had a real big bite to it, I thought."

Batmanglij: "Yeah. I think at the end of the day, we have, like, a sort of checklist for songs. Like, a song isn't successful to us, isn't worth putting on an album, unless it satisfies certain goals that are maybe more conceptual.

"But then, on another level, it has to also succeed on, is it a catchy song? Does it stick in your head? Does it satisfy you? Is the melody strong? Is the chord progression satisfying? Those things. You can't just throw African music and classical music together and feel like ... the only things necessary to make a good song. On some level, it has to succeed as a pop song, ya know? We don't get played on pop radio and that's a good time. (laughs)"

Mason: "It is?"

Batmanglij: "I think for now it's a good thing that we're not on pop radio."

Mason: "Because why? Would you be scared if you were?"

Batmanglij: "I would definitely be surprised. I might be happy. But they say that once you enter the world of pop radio, you can't come back. Like, other radio stations don't want to play you, once you're on the pop station. You enter a level where you can't be, like, Nicole Kidman who does one independent movie and then one blockbuster and then one -- it's not like that. (laughs) Once you enter the world of pop radio, the rock radio will stop playing you because, you know, you've lost all cred."

Mason: "I don't know how much radio matters anymore. But you guys have made a career without radio, so who cares, right?"

Batmanglij: "That's not true, actually. (laughs)"

Mason: "What do you mean?"

Batmanglij: "Well, we do get played on alternative radio stations."

Mason: "Right, but I mean, not mainstream pop stations."

Batmanglij: "No, but I think it's definitely been important."

Mason: "Uh-huh, the alternative stations, the college stations and stuff like that, sure."

Batmanglij: "Yeah, all of that stuff has been really important, too."

Mason: "Right. But I mean, you can almost do it now with, if you get in films, as you've done, and TV shows and stuff like that, that opens the door pretty wide, don't you know?"

Batmanglij: "Yeah, and once those doors are opened, people are more interested to play your music on their radio, as it were. (laughs)"

Mason: "So I get a sense, just in listening to the way you describe what goes into a song and what your own standards are for a song, not that you would have low standards, but it sounds like you guys are a pretty tough sell on what a good song is."

Batmanglij: "We are. And that's why on this record, we spent about a year just songwriting and just collecting ideas. And not stopping the writing process until we were at a place where we were like, 'Okay, we have enough.' "

Mason: "What was the first song you guys wrote together? In the very beginning, what was the first song you really got finished?"

Batmanglij: "Hmmm, well, we were putting together our early shows, and some of the earliest ones were 'Walcott,' 'Oxford Comma,' 'Cape Code Kwassa Kwassa,' and 'Campus' was one of the early ones, too."

Mason: "What's interesting to me, you hit out a sound really quickly."

Batmanglij: "To some extent, yes. But you have to understand, we spent four years talking about music and working on music, sometimes together and sometimes separately. And we could bring all those things together, you know?"

Mason: "Uh-huh. So you had kind of an incubator?"

Batmanglij: "Yeah, we did, we definitely did."

Mason: "Why do you think it worked?"

Batmanglij: "(Laughs) I don't know! I think, you know, somebody asked me if I believed in serendipity and I'd never thought about it until a few years ago. And I realized I do, because if we hadn't all been at Columbia, we wouldn't have met each other and we wouldn't have inspired each other in the way that we have."

WEB EXCLUSIVE VIDEO: Rostam Batmanglij on his process for writing music, and why it's a "good thing" his songs aren't played on pop radio.

WEB EXCLUSIVES: Delve more deeply into Vampire Weekend by reading an extended interview by Anthony Mason of Ezra Koenig.

For more info:

- vampireweekend.com

- "Modern Vampires of the City" (XL Recordings); Also available on iTunes and Amazon