We found our personal data on the dark web. Is yours there, too?

The little drips of personal data leaked from every major data breach—your name, email, phone number, Social Security number, and mailing address—pool in a murky corner of the internet known as the dark web. Some of these leaks might seem relatively insignificant, but criminals exploit your personal data for profit and to help other criminal operations prosper. The dark web is where these transactions happen.

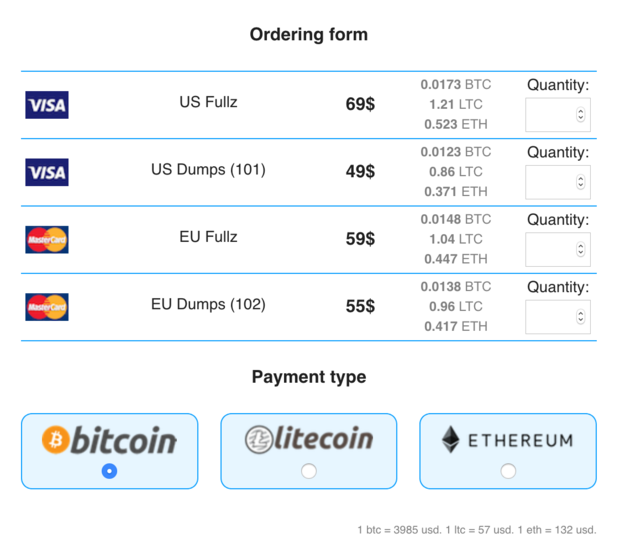

The spectrum of threat actors operating on the dark web is broad, ranging from lone wolf hacktivists to nation-states and organized criminal operations. What they have in common, however, is a lust for personal data. The recent Gnosticplayers hack, for example, obtained nearly 840 million records from 32 companies. And according to cybersecurity experts, while unique records sell for cheap—a portion of the trove was listed for 1.2431 bitcoin, or about $4,940—in aggregate our personal details help enrich these nefarious operators.

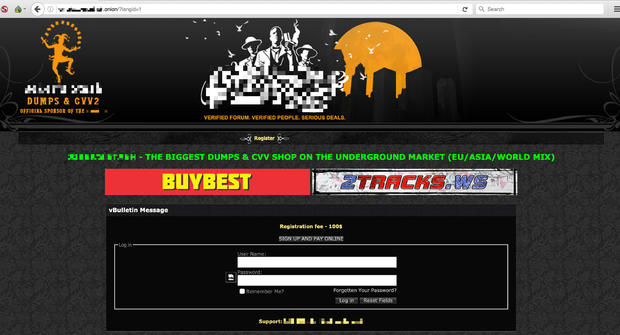

Navigating the dark web

Like the traditional internet that we use every day, the dark web is a network of websites. But unlike our traditional internet, the dark web requires special security software to encrypt browsing activity and hide a user's location and identifiable details.

There are countless legitimate uses for the dark web. Political activists living in totalitarian states use the encrypted web to share mission-critical information, and reporters in conflict regions often use the dark web to communicate with sources. But the dark web's discreet nature is also exploited by hackers and criminals to trade in weapons, drugs, stolen data, and other illicit goods and services.

Hacked personal data may seem benign relative to other harmful material for sale on the dark web, but according to Emily Wilson, the vice president of research at cybersecurity firm Terbium Labs, in the hands of criminal actors your personal data can have serious and potentially dangerous consequences.

"Data is transmitted very quickly. There's no ship time. Criminals buy it, they get it instantly, and they can cash it out," said Wilson. "Data is often good for a long time. If somebody uses your credit card, you get a fraud alert, and get a new credit card number. That's a loss to you and that's annoying. But what about your Social [Security number], what about your name, what about your address or your driver's license numbers? These are data points that can be exploited for decades or for a lifetime. And once it's out it's nearly impossible to get it back."

We asked Terbium Labs to do a deep dive into the dark web and search for any information about us that had been leaked as a result of hack. What they found was disturbing. Our personal information was mixed in with wholesale data dumps of information about thousands of people. The building blocks to not only replicate our own identities online, but everyone else packaged along with us.

"Identity theft and other scams often rely on incomplete information," wrote Wilson, in the report she prepared for us. "These scams exploit and bypass systems designed to reduce user friction first and provide security second."

One reporter's name triggered matches dating back to 2015 on what Wilson described as a "fraud site" named Black Stuff. His name also popped up among leaked email that included tens of thousands of rows of data from thousands of people. The leaks, Wilson said, may have included passwords.

Someone with the same name appears to be further compromised, she found. That person, "appears repeatedly exposed through work-related leaks of code and information, including contact details."

The other reporter was a bit more obscured, but the findings are nevertheless disturbing. An apartment building where he recently lived is lighting up the dark web.

The address "has partial matches on a series of doxes," she wrote, using a term that refers to the act of publishing someone's contact information as a sort of malicious revenge. Information from people at the residence also appeared on a fraud site called Omerta, as well as on a well-known non-dark web site: WikiLeaks. The leak in that instance involves campaign donations, and information includes people's full names, addresses (including apartment numbers), emails and even phone numbers.

Our personal records are packaged with the records from tens of thousands of other individuals. This year, the seemingly-endless parade of hacks and data breaches includes the video game Fortnite, Dunkin' Donuts, and the Dow Jones company.

The real harm, said Wilson, is that once your data is for sale on the dark web, it's likely to remain there for years to come. "You're just another cog in the wheel. You're just another resource. Data is often repackaged, resold, re-released, which means, if you're exposed once, it's going to be used hundreds, thousands, maybe even millions of times before it's all said and done."