Warren Commission kept in dark over meeting with Castro

A top-level mission to interview Fidel Castro about President John F. Kennedy’s assassination 50 years ago was kept so secret that even staff members of the Warren Commission did not know it had taken place.

In interviews on the anniversary of Kennedy’s death, some of the staff say they learned of the trip only from former New York Times reporter Philip Shenon’s new book, “A Cruel and Shocking Act: The Secret History of the Kennedy Assassination.”

“I have no independent knowledge of it,” said Howard P. Willens, a member of the commission’s supervisory staff and now a lawyer in private practice. “If it did in fact happen during the Warren Commission’s period, I’m favorably impressed.”

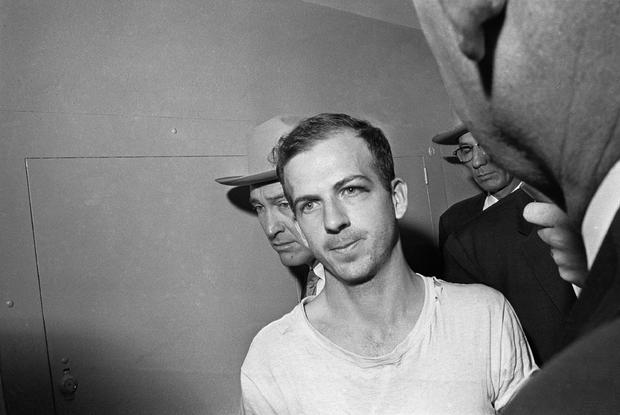

Willens and four others on the staff spoke to CBS News about their work and the many criticisms that have dogged them since their report was published 10 months after the assassination. They said that the commission’s conclusions had not been seriously challenged in the last half-century, despite four official government inquiries and a flood of books accusing right-wing zealots, Communists or President Lyndon Johnson himself, and that no credible evidence has surfaced showing Lee Harvey Oswald was part of a conspiracy.To this day most Americans remain suspicious. A new CBS News poll this month found that although the numbers are declining, 61 percent of those surveyed said that they did not think Oswald acted alone, and 56 percent said that they believed there was an official cover-up to keep the public from knowing the truth. Even Secretary of State John Kerry said that he was skeptical Oswald acted alone.

“I certainly have doubts that he was motivated by himself,” he said on NBC. “I’m not sure if anybody else was involved – I don’t go down that road with respect to the grassy knoll theory and all of that – but I have serious questions about whether they got to the bottom of Lee Harvey Oswald’s time and influence from Cuba and Russia.”Willens, Burt W. Griffin, Stuart Pollak, W. David Slawson and Richard Mosk – who reunited at Southern Methodist University in Dallas last month – acknowledged that the CIA and the FBI withheld information from them and agreed that they should have seen the autopsy photographs that U.S. Chief Justice Earl Warren refused to release.

“The

chief justice may have erred on the side of good taste, I suppose,” said Mosk,

an associate justice on the California Court of Appeal. “But we had the

testimony of the autopsy doctors who were involved and their testimony proved

to be correct, because some 19 or 20 autopsy physicians who examined the photos

later all confirmed the conclusions of the Warren Commission.”

Initially, Johnson opposed the idea and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover argued that the investigation should be left to his agency, worried that the commission would disclose CIA telephone intercepts in Mexico City and FBI mail openings in Washington, according to Willens.

“What would not emerge for some time, though, was that Hoover’s most pressing concern was to prevent anyone from criticizing the FBI for not notifying the Secret Service before the Dallas motorcade of Oswald’s presence in Dallas, based on the FBI’s ongoing investigation of Oswald after his return to the United States in 1962,” Willens writes in his new book, “History Will Prove Us Right: Inside the Warren Commission Report on the Assassination of John F. Kennedy.”

The deputy director of the CIA, Richard Helms, lied directly to him when Helms denied that any of the CIA’s activities were relevant to the investigation – including plans to kill Castro, Willens said.But that Cuba might have had more motivation to kill Kennedy did not mean the Castro regime was involved, Mosk said.

“Had we known of the activities directed at Cuba, there wasn’t much more that the commission could have done short of invading Cuba or something,” he said. “We got all the information we could possibly dig up on whether or not there was any conspiracy, whether it be Cuba or somebody else. The fact that Cuba may have had some more incentive to do it doesn’t mean that it did it.”

Slawson, a retired professor who taught at the University of Southern California Gould School of Law, said he thought Warren should have allowed him and another staff member, William Coleman, to interview the employee at the Cuban Consulate in Mexico who met Oswald when he sought a visa. Sylvia Duran had finally come out of hiding and had agreed to travel to Washington, D.C., to testify, Slawson said.

“We were very disappointed at that,” Slawson said.

Warren told him that the commission could not believe a Communist, which was not a good reason, Slawson said.

He and Coleman wanted to ask whether the rumors they had heard – that she had met with Oswald after he left the Cuban embassy – were true, and if she had met with him, why, he said.

As far as the meeting with Castro, which was with Coleman, Slawson said he it did not learn of it until much later. Though the men worked

together on investigating the possibility of foreign conspiracies, Coleman had been instructed not to tell even him, Slawson said.

“I did find out about it many, many years later, but just the bare fact that he had met Castro,” he said.

Shenon, the former reporter for The New York Times, writes that Castro and Coleman talked aboard Castro’s yacht off the coast of Cuba. Castro had sent word to Washington, D.C., that he wanted to testify to show he had had nothing to do with the assassination.

Coleman was told he should not say anything about the trip except to brief Warren, Lee Rankin, the commission’s general counsel, and possibly President Lyndon Johnson, Shenon writes. On his return, he told Warren and Rankin that he had heard nothing to undermine Castro’s claim.

“I’m not saying he didn’t do it,” Shenon quotes Coleman. “But I came back and I said that I hadn’t found out anything that would cause me to think there’s proof he did do it.”

“We can only speculate on how that came about and why it came about,” he said

Willens said the meeting spoke well of Warren, who did not want any dealings with Castro’s Cuba.

But if Castro had been involved, he would not have said so, Willens said.

“What else would he say? He’s not going to admit it publicly and I think all of the knowledge we have about his reaction to the assassination cuts the other way, that he was terrified with the prospect that his government would be implicated and that the U.S. would immediately retaliate in some way that would cause the downfall of his government,” he said.

Pollak, now an associate justice on the California Court of Appeal, said everyone on the commission took the work very seriously.

“We were all working under time pressure to complete the report. We were aware that the president wanted to get a report out so it wouldn’t affect the upcoming election,” he said.

But, he added, “We were under no pressure in terms of the conclusions.”