Voyager 2 probe moves into interstellar space

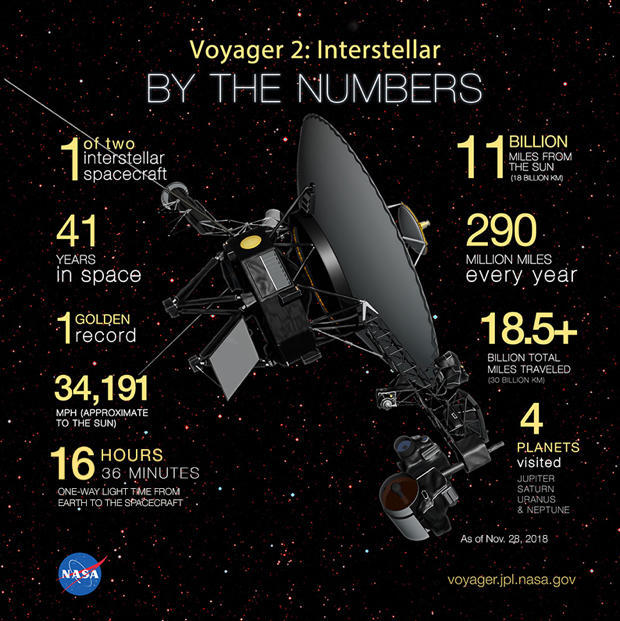

Eleven billion miles from Earth, NASA's long-lived Voyager 2 probe, still beaming back data 41 years after its launch in 1977, has finally moved into interstellar space, scientists revealed Monday, joining its sister ship Voyager 1 in the vast, uncharted realm between the stars.

Voyager 2 moved past the boundary of the heliosphere, the protective bubble defined by the sun's magnetic field and electrically charged solar wind, on Nov. 5. The transition was marked by a sharp decline in the number of charged particles detected by the spacecraft's plasma science experiment, or PLS.

The instrument has not detected any signs of the solar wind since then.

Three other instruments measured corresponding changes in cosmic rays, low-energy particles and magnetic field strength. At Voyager 2's enormous distance from the sun, it took 16-and-a-half hours for the data to make its way back to NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif.

Voyager 1 crossed the boundary of the heliosphere, a transition zone known as the heliopause, in 2012. But Voyager 1's plasma detector stopped working in 1980, and the new data from Voyager 2 provides fresh insights into the nature of the boundary between interstellar space and the sun's magnetic and electrical influence.

"Working on Voyager makes me feel like an explorer, because everything we're seeing is new," John Richardson, principal investigator for the PLS instrument at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, said in a statement. "Even though Voyager 1 crossed the heliopause in 2012, it did so at a different place and a different time, and without the PLS data. So we're still seeing things that no one has seen before."

Voyager 2 was launched in August 1977, 16 days before Voyager 1, which explored Jupiter, Saturn and Saturn's large moon Titan before heading out into the depths of the solar system. Voyager 2 flew past Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune before it, too, left the realm of the major planets.

"Voyager has a very special place for us in our heliophysics fleet," Nicola Fox, director of the Heliophysics Division at NASA Headquarters, said in a NASA statement. "Our studies start at the sun and extend out to everything the solar wind touches. To have the Voyagers sending back information about the edge of the sun's influence gives us an unprecedented glimpse of truly uncharted territory."

While both Voyagers have now departed the sun's heliosphere, they are still inside the solar system as it's currently defined. That boundary is the outer edge of the Oort Cloud, a vast collection of rocky debris left over from the formation of the solar system 4.6 billion years ago that is held in place by the sun's gravity.

At its current velocity, it will take Voyager 2 another 300 years or so to reach the inner boundary of the Oort cloud and possibly 30,000 years to move beyond it.