Voices from inside San Quentin

"The Q" is shorthand for San Quentin, the notorious prison located just across the bay from San Francisco. Despite its reputation, some things are changing within its walls, as we hear from "Sunday Morning" senior contributor Ted Koppel:

It's difficult to imagine a more forbidding place with a lovelier view than San Quentin. Alcatraz, perhaps; but that went from prison to tourist attraction 45 years ago.

San Quentin – "the Q," as it's known – has stood as a grim monument to punishment since 1852.

The outside world got an inkling of conditions inside when Johnny Cash performed this song in, and about, San Quentin, for an audience of raucously appreciative inmates almost 50 years ago:

San Quentin, may you rot and burn in hell.

May your walls fall and may I live to tell.

May all the world forget you ever stood.

And may all the world regret you did no good.

That was 1969. But even 12 years later, when Lonnie Morris got here, it was in every way a volatile, dangerous place: "Which meant you could be stabbed, and if it was against the police, you could be shot, or you're in a conflict with another incarcerated person, you could be shot by the police in their effort to break up a violent conflict."

The inmate population continues to have its share of violent criminals, and – for the most part – the men still self-segregate along ethnic and racial lines. "Prison politics" they call it – an unwritten set of rules that still carry weight.

Koppel asked Earlonne Woods (who has spent 20 of his 46 years in prison),"If I started going through the cell blocks here, how many times am I going to see a white guy in the same cell as a black guy?"

"Probably twice," Woods replied.

"So, that hasn't changed?"

"No. It hasn't changed. It think that's been in play for, like, 100-something years."

Don't get the wrong idea; San Quentin has changed – that's what this story is all about. It used to be a level four maximum security prison, now it's level two, with a serious emphasis on rehabilitation.

"One of the reasons why I came here was 'cause there's a lot of [educational] programs," said a "lifer" named Johnny.

For instance, there a class in computer programming; there's the prison newspaper, the San Quentin News, with seven civilian advisers – professional journalists – but which is staffed by inmates. And there are actual college classes.

Johnny applied to come to San Quentin. "So, it's kind of like going to college?" asked Koppel.

"Yeah. And it's free!" he laughed.

Now, that's bound to raise a few hackles: This image of several thousand hardened criminals – robbers, rapists, killers – broadening their cultural horizons at some taxpayer-supported campus by the Bay. Take another look, though; San Quentin remains very much a place of punishment – a correctional institution.

"You can come here and become a better person, a better individual, by coming to prison," said inmate Andre Yancy.

No, no, no, no! Come, let's away to prison:

We two alone will sing like birds i' the cage:

When thou dost ask me blessing, I'll kneel down,

And ask of thee forgiveness: so we'll live,

And pray, and sing, and tell old tales, and laugh. – "King Lear"

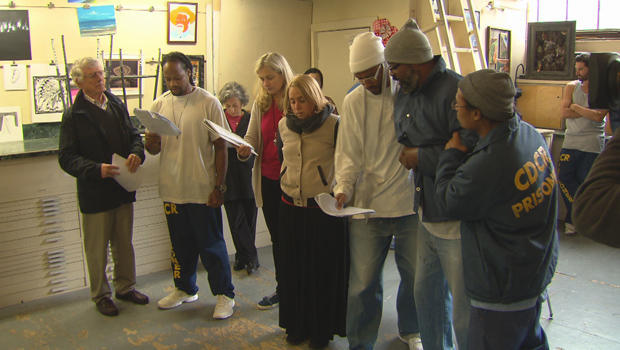

Members of the Marin Shakespeare Company – including women – are civilian volunteers helping inmates mount a production of "King Lear."

The director asked one actress, "How do you feel before you come on in the scene? How do you feel about your sisters at this point?"

"I've already decided I'm going to kill her," she laughed.

The themes of trust and betrayal woven throughout "King Lear" have a unique resonance for this group of actors. One inmate explained, "I give you my full authentic self. You give me this character the whole time. So, like, that's a big betrayal."

"All the more reason to really take our time to really get to know someone, not just our image of them," said the director.

"Not just the superficial surface that you know, but the internal deep that you know?"

"Absolutely. And that takes time, that takes time."

"We have nothing but time here!"

Nothing but time. Thirty-five years ago, CBS News correspondent Gary Shepard focused on the problem of overcrowding at San Quentin: "The prison system's answer has been to put two inmates into a tiny cell – six feet wide by eight feet long, designed to barely accommodate a single prisoner."

Thirty-five years later: Same cells, same overcrowding.

"You don't have a helluva lot of room in here, do you?" Koppel asked Woods.

"I don't. You know, it's like one person can move at a time. Like, we have to turn sideways!"

Woods is of particular interest because of his day job: He and Koppel are in a similar line of work.

"I'm Earlonne Woods, a prisoner at San Quentin State Prison in California. I'm serving a 31 year-to-life sentence for being a getaway driver of an attempted second-degree robbery. You're now tuned in to San Quentin's Ear Hustle from PRX's Radiotopia."

Ear Hustle is a podcast that tells the stories of inmates and of life inside prison. "Ear Hustle basically means eavesdropping in on conversations," Woods said.

Did he know what a podcast was before he started doing one? "No, I didn't!" he laughed.

Woods co-hosts and also co-produces Ear Hustle with a civilian, Nigel Poor: "I came in out of curiosity. I wanted to know what life was like inside prison. And I had a lot of assumptions that most people have, that the guys in here were gonna be scary, that it was gonna be dangerous. And through spending time here, that was really changed."

BULLOCK: "My name is Stacey Bullock and I have a 150 years-to-life."

WOODS: "So, how old will you be when you go to parole after 150 years?"

BULLOCK: "Something like 208 years!"MAN: "I was sentenced to 1,002 years and 19 life terms for an armed bank robbery."

POOR: "That's what we're talking about on this episode – hope and hopelessness in the face of these really long sentences."

MAN: "I won't go up for parole until Jesus comes back first."

Woods said, "What we try our best to do is go to the yard and find stories that are compelling, that are funny, and we try our best to tell 'em. And we try to do 'em in a way where people [outside] can identify with 'em."

Ear Hustle focused one podcast on solitary confinement – what prison authorities call Security Housing Units, or the "SHU." Also known as the Hole, the Box, the Dungeon.

RICHARD JOHNSON: "I was sitting there thinking, is this it? I mean, I saw no future. How do I spend the next 20, 25, 30 [years] 'til I die in this cell? Because I wasn't prepared for it."

Until prisoners filed a successful class action lawsuit against the California prison system, inmates could spend unlimited years in solitary confinement. Now, at least, there's a five-year cap.

Before he was transferred to San Quentin from Pelican Bay, Richard Johnson spent 19 years in the SHU: "Not that I actually did anything, but they were saying I was a gang member or something," Johnson said.

Koppel asked, "Were you?"

"Not really."

"Oh, come on. 'Not really' is bullsh*t. 'Not really' means, 'Yes, I was, but…'"

"At the time."

"At the time! Solitary is used in some countries to drive people crazy, and then that's the whole point of it."

"Right. That was their intent. But I'm resisting, you know? Still resisting, because you don't fully get over that."

JOHNSON: "Never allow anyone to make you less than what you are. That's the true intent of isolation. It's to belittle you, demean you, dehumanize you, to make you less a person than what you are."

When asked what he cannot talk about on his podcast, Woods said, "Haven't got there yet. So, I don't know what we can't talk about yet."

San Quentin's Public Affairs Officer, Lt. Sam Robinson, is the ultimate decider. He could block a subject. Although he told Koppel, "There hasn't been that instance yet. There have been some that weighed mightily on me, [like] the podcast 'The Boom Boom Room.'"

And what is the "Boom Boom Room"? "A name that's I've given to a place where, I guess, people conjugate, where people come together, and do what people do!" he laughed.

PRISONER: "For me, it was like getting a taste of freedom. And then for her, it was like getting a taste of her husband."

PRISONER: "I'm standing against the wall. She just like leaned against me with her head on my chest. And we talked without talking, you know? It was like we was a regular couple. We wasn't in prison. We was just us. Yeah."

"I let it go through," said Lt. Robinson. "Because it was true and authentic and it represented conjugal visits are even much more than what we in society believe is just this opportunity to do what adult people do. [It's] being a family."

Ear Hustle is doing something unique in the history of San Quentin: It is conveying the stories and voices of society's outcasts literally around the world. It is, Nigel Poor said, "shockingly popular," with about eight million downloads to date.

For each program? "No, our first season!" laughed Woods. "That would be cool!"

The most vulnerable among these prisoners have often been punished well beyond the sentence that any court handed down, and they are desperate to have somebody – anybody – listen.

Convicted of an armed robbery, Curtis Roberts is doing 50 years to life:

ROBERTS: "I was raped in prison and it took something out of me. But then when the rape happened, it was like, ain't nobody coming to rescue you, Curtis. Ain't no way you're getting out of this; and this is what you have to live with for the rest of your life."

Roberts was one of the subjects of an Ear Hustle podcast last season. He told Koppel, "There was a little girl that came in here to the prison and – my definition, 'a little girl,' high school girl. She heard the podcast and she said, 'Curtis, if you don't mind, I'd like to share my secret with you.' I said, 'What's your secret?' She says, 'Curtis, I was raped like you were.' And I was like, oh, my heart just broke, you know?

"She promised me that was gonna go home and tell her mom and dad, and it was no longer gonna be her secret. And so to me, that, finally, Curtis Roberts has done something good."

Someone in the California Governor's Office clearly agrees, because Roberts is being considered for clemency.

Roberts said, "I've never used a cell phone. I don't know technology out there. I'm pretty nervous."

Freedom can be a scary prospect after decades in prison. Earlonne Woods and Nigel Poor were out on the yard a few weeks back, interviewing inmates on just that:

INMATE: "I've been in this little bubble. Prison is its own world. Being in here I can tell you that this is a whole different world, whole different society than it is out there. It is so big and so vast in society right now that I feel a little overwhelmed, I feel like I'm going to be a little bit overwhelmed. But I welcome it."

Woods said, "This is a prison where you have a lot of people that have been incarcerated over a decade, and individuals are on the trajectory to go home. So, they're trying their best to change their life. They're trying their best to apply themselves in programs, and immerse themselves in programs."

Koppel said, "I'm confused by one thing you said, Earlonne: You say a lot of people here are preparing to go home. And I'm hearing a lot of people here – 33-to-life, 50-to-life, 199-to-life ..."

"Yeah, but that don't change. That don't stop you from changing your ways and changing your life just because I have 1,000 years-to-life," Woods replied. "You never know what may happen tomorrow."

And, thanks to a prison podcast, that's a message being heard regularly now beyond the razor wire and these old walls.

For more info:

- Ear Hustle podcasts

- San Quentin News

- nigelpoor.com

- Marin Shakespeare Company's Shakespeare in Prison program

Story produced by Dustin Stephens.