Growing concerns that special education students are falling behind as classes go remote

With more schools set to open next Monday, some districts are scrambling to hire school nurses. Less than 40% of schools employed a full-time nurse before the coronavirus pandemic. There are also growing concerns for the seven million children who receive special education services.

Remote learning has been a tremendous challenge for 6-year-old Calvin Latham.

"This spring a lot of kids with disabilities didn't soar in that environment," said Toby Latham, Calvin's father.

The rising first-grader from Virginia has a brain malformation, making him one of seven million children in the U.S. receiving special education services.

"He needs hand-over-hand support for writing exercises and the cutting and gluing and the basic things a first-grader would do," said Latham.

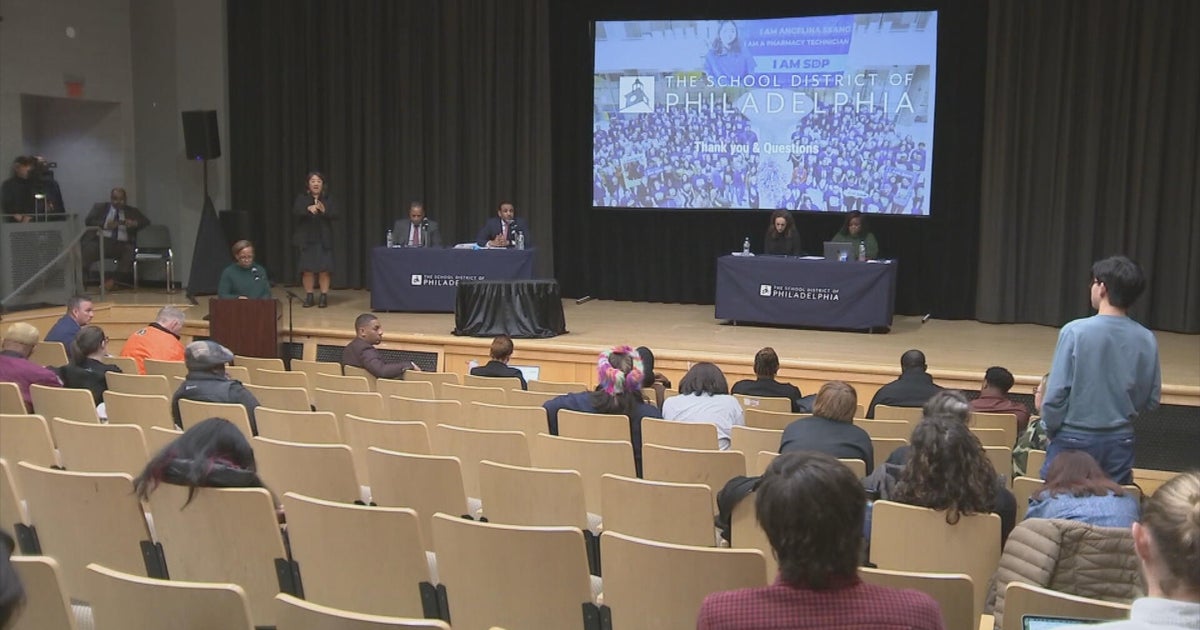

Many special education students are legally guaranteed services, like an aide, through individualized education plans, or IEPs. But in a May survey, nearly 40% of parents whose children have an IEP said their kids didn't get any support last spring.

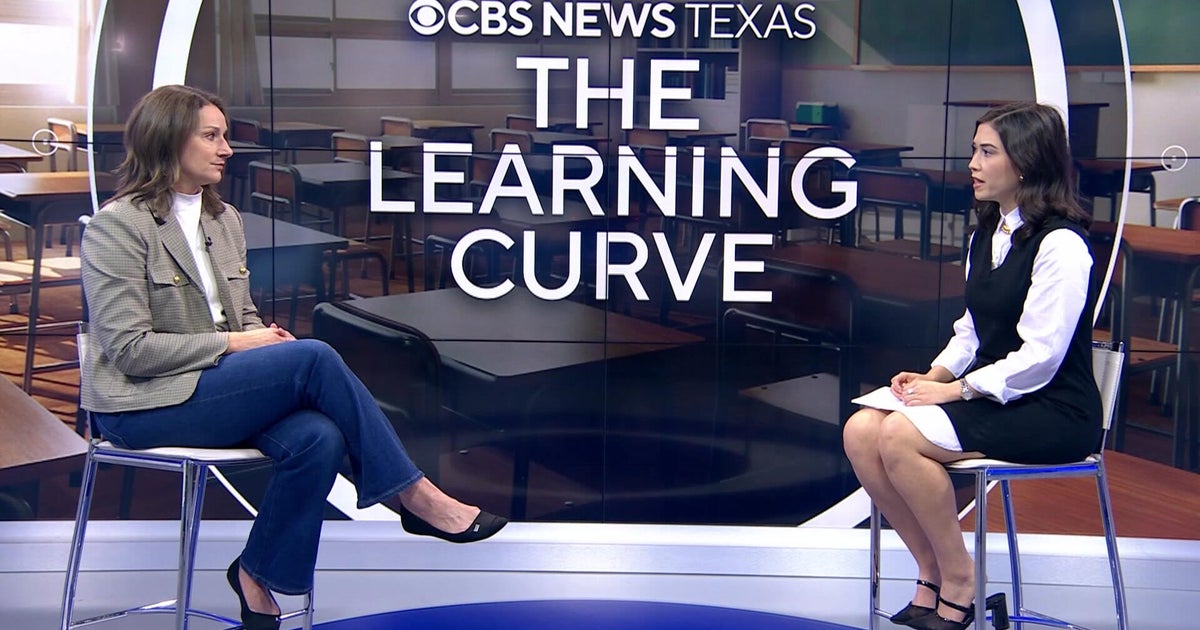

"Are you concerned that you're losing something with that one-on-one interaction if you have to go to all-remote?" CBS News asked Angie Abdelrehim, who teaches special education in New Jersey.

"Absolutely," Abdelrehim responded. "I do know there is going to be a lack in what they need to progress."

John Eisenberg, who runs the National Association of State Directors of Special Education, said it's beyond challenging.

"I think you're going to see an increase of lawsuits because schools, no matter what cost, probably cannot implement the IEPs in some cases because of the funding shortages," he said.

Without increased funding, Eisenberg said it will be a daunting task to get kids like Calvin back into the classroom.