Violins: Playing on works of art

The great luthiers of the Italian town of Cremona were the masters of musical "string theory" - no one has done better in the art of making violins. Dean Reynolds reports on their craft, and the artists who play their works of art:

As the sound wafts across Lake Austin, deep in the heart of Texas, it is so much more than a mere meeting of bow and string. There's a kind of physiological chain reaction that starts in your ears . . . sends shivers down your spine . . . and tickles your toes.

Especially when it is the work of master musician and concert violinist Anne Akiko Meyers.

"Each violin to me is like a different living soul," she said. "They each have their own personalities, and you're instilling your personality into this piece of wood that is very much alive."

And this isn't just any violin: It's the most expensive violin in the world!

"It's not in a museum! It's incredible that it's in front of us," she said.

The $16 million del Gesu, an instrument made in 1741 by a man named Guarneri del Gesu, in the small Italian town of Cremona. He was a luthier -- someone who works on stringed instruments.

But he wasn't the only luthier in Cremona. Antonio Stradivari was perfecting his violins there at the same time.

Meyers has a Stradivarius, too, made in 1730, and once belonging to the King of Spain.

"So you're feeling vibes from 300 years ago?" Reynolds asked.

"Absolutely, absolutely -- 273 to be exact!" she laughed.

The unwavering design of the instrument, especially its arched shape -- together with the thickness of the wood -- are what give a violin its sound.

"It's mind-boggling to think that eighteen inches of wood made in 1700 can produce such an incredible, glorious sound," said Meyers.

Violin making, says Michael Darnton, still follows the 18th century master plan. At his workshop in Chicago, he uses the same form that Stradivari used. He told Reynolds it takes 80-100 hours to turn out a violin.

"They're just incredibly efficient little amplifiers," said Darnton's partner, Stefan Hersh. "And this little box like this, as light as it is -- it really doesn't weigh much at all -- can fill a 3,000-seat hall with sound and everybody in the room can hear it."

Hersh says the classic centuries-old violins have been modified for modern-day use: "Not in any way that's essential to the design of the box, but in the way the strings are strung over the box."

"How do you modify a work of art?" asked Reynolds.

"Very carefully!"

The funny thing, though, is that while the del Gesu and Stradivarius violins are still considered the best ever made, a recent test of blind-folded violinists found they had a hard time distinguishing old from new. In fact, a tested Stradivarius was the least preferred, while a brand new violin was top-rated.

But it's doubtful a new violin would have caused the same kind of sensation that the Lipinksi Stradivarius did when it was stolen in an armed robbery in Milwaukee last year.

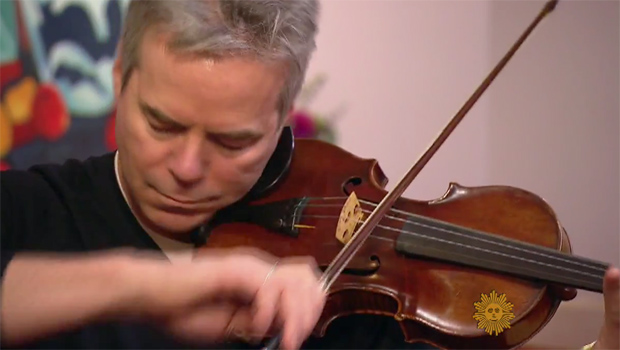

Made in 1715, the Stradivarius (worth $5-6 million) was taken from Frank Almond, concert master for the Milwaukee Symphony.

"The only thing I can compare it to is maybe watching one of your children get kidnapped or something," Almond said.

Police recovered the violin from two suspects in a matter of days.

- Violin heist ends on sour note for suspects ("CBS Evening News," 02/07/14)

"What is so great about a Stradivarius?" asked Reynolds.

"Well, you know, to us that's sort of like, 'What's so great about the Mona Lisa? Why can't anybody paint the Mona Lisa anymore?'

"I spend a lot of time with this, more time with this probably than anyone or anything else in my life -- that's sort of what I do," Almond added. "So it's hard not to get wrapped up in it. I spend a lot of time trying to keep that divide in check."

"Do you talk to it?" asked Reynolds.

"No, I don't go that far!" he laughed.

We don't know if Anne Akiko Meyers talks to her violins, but they certainly speak to her - and to us.

"It's got major kick," she said, "and it's ballsy and it's gutsy and it's dark and it has just a whole range of color that I can explore. And so, it makes me freer as a musician."

For more info:

- Anne Akiko Meyers (Official website)

- Anne Akiko Meyers' blog

- "The American Masters: Barber, Corigliano, Bates" - Performed by Anne Akiko Meyers, with the London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Leonard Slatkin (eOne Records); Available via Amazon and iTunes

- Follow @AnneAkikoMeyers on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube

- Michael Darnton, violin maker

- Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra