Violence against abortion clinics hit a record high last year. Doctors say it's getting worse.

For one of the last abortion doctors in Missouri, harassment, stalking and death threats are a part of regular life. But this year, it's been worse than ever.

Colleen McNicholas, the chief medical officer at Planned Parenthood of the St. Louis Region and Southwest Missouri, is one of many providers who told CBS News they've seen an uptick in violence this year, both against themselves and their clinics. They say the increased harassment has coincided with newly enacted state laws restricting legal abortion and polarizing rhetoric surrounding the procedure.

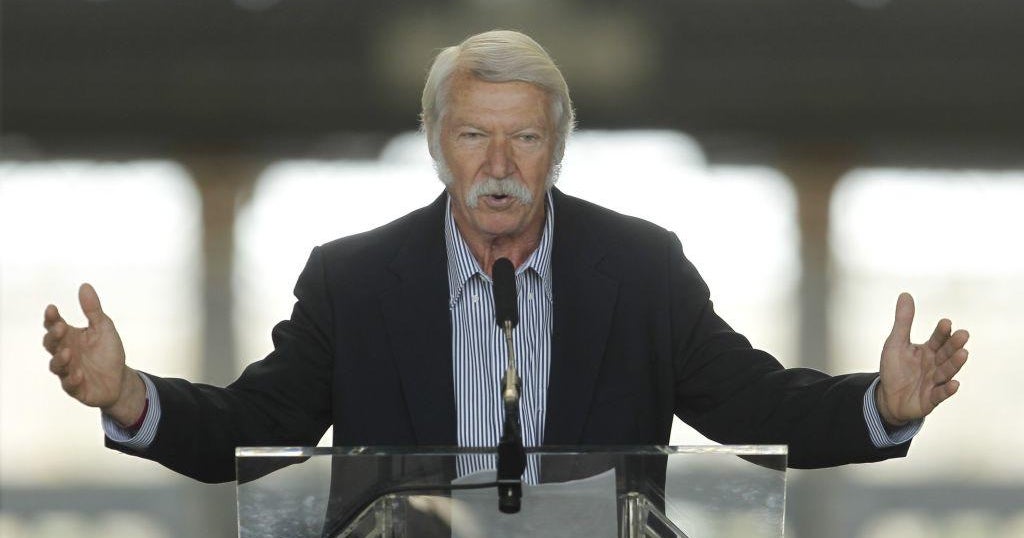

The National Abortion Federation has been tracking violence against abortion providers and clinics since 1977. The Very Reverend Katherine Hancock Ragsdale, an Episcopal priest and interim president & chief executive officer of the organization, said the violence that providers face today is "beyond anything we've ever seen before."

"We're seeing a dramatic increase in violence and disruption against clinics," she said in an exclusive interview with CBS News.

In 2017, violent acts against abortion providers more than doubled from the year prior, according to data compiled by NAF. The group recorded 1,081 violent acts, the most since the group began tracking these incidents.

Last year, the group recorded another new record high: 1,369 reported violent acts, including 15 instances of assault and battery, 13 burglaries, 14 counts of stalking and over a thousand episodes of illegal trespassing.

In interviews with nearly one dozen clinics, including McNicholas's St. Louis Planned Parenthood, providers say the situation is getting worse. In August alone, three young men were arrested for threatening mass shootings against Planned Parenthood facilities. At the home of one of the suspects, authorities seized 15 rifles, 10 semi-automatic pistols, and 10,000 rounds of ammunition during a raid.

As Missouri has emerged on the front lines of the nation's debate over abortion access, McNicholas has become the face of that battle. She's been a staple at nearly every protest, courtroom hearing and press conference.

But becoming a vocal defender of abortion access in Missouri has made her a target. Protesters have followed her coming to and from work. In the midst of fighting a very public battle to keep the clinic in operation, McNicholas told CBS News that she was advised to increase the security protocols at her home. She declined to give specifics for safety reasons. Security protocols at the clinic are constantly under review, said a spokesperson for Planned Parenthood.

Ragsdale and the providers interviewed by CBS News said they've seen a direct correlation between the rise in violence and the wave of anti-abortion legislation passed this year. So far in 2019, lawmakers in the South and Midwest have passed 58 restrictions, nearly half of which would ban the vast majority of abortions in their respective states, according to data compiled by the Guttmacher Institute, an abortion rights and reproductive health research organization.

Julie Burkhart, the founder and chief executive officer of Trust Women, a network of abortion clinics, knows firsthand the potential danger that abortion providers face. Ten years ago, her mentor, Dr. George Tiller, was assassinated at church by an anti-abortion extremist. At the time, Tiller was a high-profile abortion doctor, known nationally for providing the procedure later into women's pregnancies. In an interview with CBS News, Burkhart said today's anti-abortion environment feels similar to that of 2009.

"I'm just so unsettled and fearful that we're going to see people hurt," she said. "My boss was murdered. I fear that we're going to have the same horrible outcome."

Ragsdale said anti-abortion violence tends to go hand in hand with anti-abortion legislation, adding that "you can pretty much always draw a line from public rhetoric to violence." Inflammatory language — like referring to abortion as "infanticide" and doctors as "baby killlers" — can be a "dog whistle" to anti-abortion extremists and can push them into action, Ragsdale said.

At Whole Women's Health, a network of seven abortion clinics across Indiana, Maryland, Minnesota, Texas and Virginia, anti-abortion protesters are a constant, said Amy Hagstrom Miller, the group's chief executive officer and president. But earlier this year, as states were passing abortion bans and federal lawmakers considered the "Born-Alive" bill, the situation worsened, Miller said in an interview with CBS News.

"These aggressive bills that keep getting introduced have a tone to them that's incredibly fringe and introduces violent language," Miller said, noting that in Alabama's legislation for a near total ban on abortion, lawmakers compared the procedure to the Holocaust, the Khmer Rouge "killing fields," and other modern genocides.

This spring, protesters scaled her clinic's fences, blocked clients from entering the parking lots and even stopped patients from closing their cars' doors as they tried to leave, Miller said. In April, her clinic in McAllen, Texas, was the target of an arson attack, something Miller believed to be directly related to President Trump's comments on the Senate's failed "Born-Alive" bill, legislation that would require doctors to resuscitate infants born after a "botched abortion."

However, as many abortion rights advocates pointed out at the time, the instance described in the bill "virtually doesn't happen." Even if it did, it's already covered: a bill passed in 2002 already requires physicians to provide that care.

At the time of the vote, in a pair of tweets, Mr. Trump said, "the Democrat position on abortion is now so extreme that they don't mind executing babies AFTER birth."

"When you put something like that out there, it can motivate anti-choice people to act," Senator Mazie Hirono, a Democrat from Hawaii, said in an interview with CBS News. "That's what happens when you call a whole bunch of people 'baby killers.' The rhetoric is very, very harmful."

Hirono spoke out strongly against the legislation and her position — and subsequent vote against the bill — earned her "hundreds" of threatening voicemails and emails, some of which were death threats that required her to increase her office's security, Hirono told CBS News.

"I'm really afraid that this kind of language will motivate people to do something harmful and violent," Hirono said.